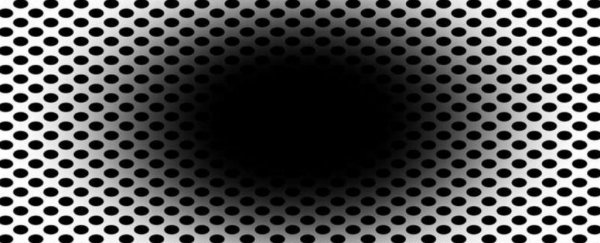

A new optical illusion can trick most of us into perceiving an expanding black hole, new research reports.

The image is completely static, but researchers say it gives people "a growing sense of darkness, as if entering a space voided of light".

The illusory forward motion is probably our mind's way of preparing us for a change of scenery. By predicting a change from brightness to darkness, our visual system can adjust much faster to potentially perilous conditions, the researchers suggest.

"Just as glare can dazzle, being plunged into darkness is likely risky when navigating into the darkened environment," the authors write in their new paper.

"Although, as in any illusion, this virtual expanding darkness is experienced at the cost of veridicality, since the observer is neither moving forward nor entering any dark space, such a cost is likely to be less severe than if there were no corrections when an observer really moved forward into a dark space."

The 'expanding hole' illusion. (Laeng et al., Front. Hum. Neurosci., 2022)

The 'expanding hole' illusion. (Laeng et al., Front. Hum. Neurosci., 2022)

The first study to analyze this optical illusion explored how the color of the hole and the surrounding dots affect our mental and physiological responses.

To do this, a group of 50 participants with normal vision were presented with 'expanding hole' images of various colors on a screen. In the series, they were also shown scrambled versions of the illusion with no discernible pattern in light or color.

The illusion of forward motion was most effective when the hole was black. In this shade, 86 percent of participants felt as though the darkness was headed towards them.

Tracking the eye movements of participants revealed their pupils were unconsciously dilating at the sight of the black hole.

Meanwhile, if the hole was white, their pupils contracted only a little.

"Here we show based on the new 'expanding hole' illusion that that the pupil reacts to how we perceive light – even if this 'light' is imaginary like in the illusion – and not just to the amount of light energy that actually enters the eye," says psychologist Bruno Laeng from the University of Oslo in Norway.

"The illusion of the expanding hole prompts a corresponding dilation of the pupil, as it would happen if darkness really increased."

The authors aren't sure why 14 percent of the group did not perceive any illusory expansion when the hole was black. But even among those who did perceive the illusion, the strength of the sensation varied.

The people who felt the illusion strongest were also those whose pupils' diameters changed the most.

"Our results show that pupils' dilation or contraction reflex is not a closed-loop mechanism, like a photocell opening a door, impervious to any other information than the actual amount of light stimulating the photoreceptor," says Laeng.

"Rather, the eye adjusts to perceived and even imagined light, not simply to physical energy."

The authors have a hypothesis for why the eye can do this. When the central region is black, our pupils are probably preparing us for a change of luminance in the near future.

Instead of seeing the information that is presented directly in front of us, the visual neural network predicts how that information will change in the future, generating "an illusory 'outward expansion' of the central 'hole' region".

If the brain didn't do this, it would have taken milliseconds longer for the new visual information to reach higher processes in the brain. If it took this long for our pupils to dilate we might not be able to navigate the darkness as efficiently.

The authors now want to test whether other animals are also tricked by the illusion to better understand how the human visual system evolved.

The study was published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.