Researchers have discovered that an injection of a protein called IL-33 can reverse Alzheimer's-like symptoms and cognitive decline in mice, restoring their memory and cognitive function to the same levels as healthy mice in the space of one week.

Mice bred to develop a progressive Alzheimer's-like disease as they aged (called APP/PS1 mice) were given daily injections of the protein, and it appeared to not only clear out the toxic amyloid plaques that are thought to trigger Alzheimer's in humans, it also prevented more from forming.

"IL-33 is a protein produced by various cell types in the body and is particularly abundant in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord)," says lead researcher, Eddy Liew from the University of Glasgow in the UK. "We found that injection of IL-33 into aged APP/PS1 mice rapidly improved their memory and cognitive function to that of the age-matched normal mice within a week."

Before we go any further, we should make it clear that these results are restricted to mice only, and at this stage, we have no idea if they will translate at all in humans with Alzheimer's.

And the odds aren't great - one study put successful translation of positive results in mice to humans at a rate of about 8 percent, so we can never get too excited until we see how things fare in human trials.

But when it comes to a disease with no known cure that's expected to affect 65 million people by 2030, any new development is worth a look at, and the team behind the discovery reports "encouraging hints" that certain aspects of this study could translate to human Alzheimer's patients.

In humans, Alzheimer's disease usually results from a build-up of two types of lesions in the brain - amyloid plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles.

Amyloid plaques sit between the neurons and form dense clusters of a sticky type of protein called beta-amyloid.

Neurofibrillary tangles are found inside the neurons, caused by defective tau proteins that clump up into a thick, insoluble mass. This causes tiny filaments called microtubules to get twisted, which disrupts the transportation of essential nutrients around the brain.

Right now, no one knows why certain people experience a build-up of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain as they age, and others don't, but scientists are confident that if we can figure out how to clear them out and stop them forming, we can effectively treat the disease.

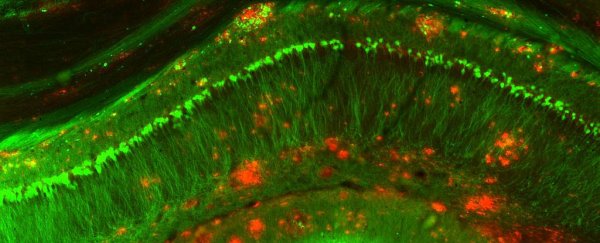

Working with mice, Liew and his team discovered that IL-33 appears to kickstart immune cells in the brain called microglia, directing them towards the toxic amyloid plaques.

Once the plaques were on their radar, the microglia aggressively targeted and absorbed them with the help of an enzyme called neprilysin, which is known to break down soluble amyloid.

This process was found to reduce the size and number of amyloid plaques in mice with Alzheimer's-like symptoms.

Not only that, but the IL-33 injections also prevented inflammation in the brain tissue, which previous studies have linked to the proliferation of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.

"Therefore IL-33 not only helps to clear the amyloid plaque already formed, but also prevent the deposition of the plaques and tangles in the first place," the Glasgow team reports.

So it's good news for APP/PS1 mice everywhere, and a very interesting result for researchers around the world who are hell-bent on finding a cure or treatment for Alzheimer's disease in humans. Liew remains cautiously optimistic:

"The relevance of this finding to human Alzheimer's is at present unclear. But there are encouraging hints. For example, previous genetic studies have shown an association between IL-33 mutations and Alzheimer's disease in European and Chinese populations. Furthermore, the brain of patients with Alzheimer's disease contains less IL-33 than the brain from non-Alzheimer's patients."

He adds that, "There have been enough false 'breakthroughs' in the medical field to caution us not to hold our breath until rigorous clinical trials have been done," but says they're just about to enter a Phase 1 clinical trial with human patients to test the toxicity of IL-33 at the doses used in mice.

We're ready and waiting for those results.

The research has been published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.