The Universe can be a bit like a magic trick. When you shift to look at the different wavelengths of light, you can see all sorts of objects, events and interactions that are otherwise invisible to the human eye.

Using the Very Large Array telescope in New Mexico, astronomers led by Marie-Lou Gendron-Marsolais of the European Southern Observatory have peered into a humongous galaxy cluster. There, in low frequency radio wavelengths, they've seen the complex invisible haloes that could be a result of intense galactic interactions.

There's a lot more to a galaxy than the visible light it gives off. Many, including the Milky Way, have large-scale radio structures, vast bubbles or jets of radio emission extending far above and below the galactic plane. In many cases, these lobes and jets are well defined and more-or-less symmetrical.

In the Perseus cluster, located in the constellation of Perseus some 240 million light-years from the Milky Way, a different picture emerges.

The Perseus cluster is huge, one of the most massive objects in the known Universe. It contains thousands of galaxies enveloped in a huge cloud of hot gas. And the new VLA images - the first in high resolution in the low-frequency 230 to 470 mergahertz range - reveal previously unseen details in the large-scale radio structures.

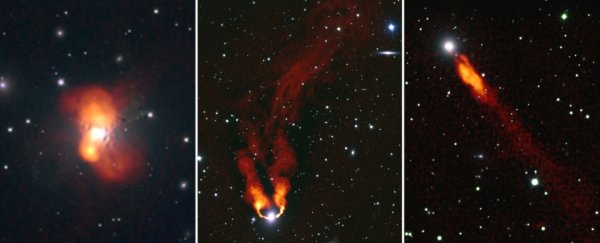

The galaxy NGC 1275, also known as Perseus A, sits right in the centre of the cluster, and it's the brightest galaxy therein. In its inner lobes, the observations reveal new substructures - thin filaments of radio emission, and loop-like structures in the southern lobe. The observations also confirmed the presence of radio spurs in the outer lobes, first detected in 2002.

Meanwhile, the galaxy NGC 1265 has two long jets - but they're bent at 90-degree angles, trailing into a single, comet-like tail that curves around. This structure is well known, but puzzling; such tails are usually interpreted as motion tracers through the intracluster medium, caused by ram pressure. Based on an analysis of difference in brightness in the tail, the team interprets this shape as evidence of two separate electron populations.

They also identified new filaments of radio emission in the tail, although at this stage it's difficult to say what created them. It could have been turbulence, or magnetic fields; higher resolution images will be needed for a more detailed analysis.

The galaxy IC 310 is likewise a tailed galaxy, although its tail is straight, which is much more normal, consistent with a radio galaxy falling into the cluster. But recent research revealed this galaxy to be a blazar, with a jet of material shooting at near-light speed from the galactic nucleus in the direction of the observer (that's us here on Earth).

Because of the viewing angle, the team was able to observe gamma radiation from the galactic centre, as well as new structures in the tailed jets - two distinct, narrowly collimated jets at the base of the tail. According to their analysis, the observations are consistent with a blazar, implying that bent-jet radio galaxies and blazars are not mutually exclusive.

Galaxy clusters are strange places, filled with interactions and objects we don't understand well at all. These new observations are breadcrumbs on the learning trail… but they also highlight the importance of getting in there with the most powerful telescopes we can muster.

"These images," Gendron-Marsolais said, "show us previously-unseen structures and details and that helps our effort to determine the nature of these objects."

The team's research has been accepted into the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and is available on arXiv.