In the outer Solar System, far from the light and warmth of the Sun, things can get a little… hinky.

There, clusters of rocks have been orbiting in weird loops that some astronomers have attributed to the presence of a large, unseen planet lurking on the Solar System's fringes.

So far, searches for the hypothetical Planet Nine have yielded no such world. There are many possible reasons for this, one strong contender of which is that there is no Planet Nine, and there never was.

But if this is the case, how do we explain the orbits? Well, a new paper has a potential solution: an alien star.

No, of course it's not there now. But once upon a time, billions of years ago, a massive object could have passed closely enough to gravitationally stir up the orbits of objects in the outer Solar System, causing the peculiar orbits. Some of those outer objects could have even ended up much closer to the Sun, now seen as strange moons captured by the giant planets.

That's the conclusion reached by a team of astrophysicists led by Susanne Pfalzner of Forschungszentrum Jülich in Germany, who performed computer simulations to observe the effects stars of varying masses and distances have on the outer Solar System as they zoom by.

"The best match for today's outer Solar System that we found with our simulations is a star that was slightly lighter than our Sun – about 0.8 solar masses," explains astrophysicist Amith Govind of Forschungszentrum Jülich.

"This star flew past our Sun at a distance of around 16.5 billion kilometers. That's about 110 times the distance between Earth and the Sun, a little less than four times the distance of the outermost planet Neptune."

Most of the stuff inside the Solar System orbits in a more-or-less flat disk configuration. It's a relic of the way the Solar System formed; when the Sun was a spinning baby star some 4.6 billion years ago, material from the cloud around it swirled around it and fed its growth. Over time, this whirling material flattened into a disk – a lot like a ball of pizza dough flattens out as it spins.

What the Sun didn't devour then turned into the Solar System, with all the planets and asteroids and moons. And, because nothing majorly disruptive happened to the Solar System, that disk is where all of those planets and asteroids and moons stayed, more or less.

But the outer Solar System is different. There are swarms of rocks that orbit the Sun our past the orbit of Neptune – the trans-Neptunian objects, or TNOs – at remarkably inclined angles. Some of these angles are so inclined that the object almost orbits the Sun's poles, instead of its equator.

These orbits, some scientists point out, are consistent with the gravitational influence of a planet up to five times the mass of Earth. But space is far from empty, and although there are no stars very close to the Sun now, once upon a time, there were probably more. Stars are usually born in clouds where many other stars are born, and start their lives in pretty crowded environments.

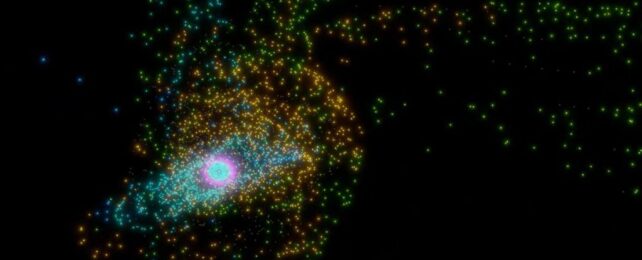

Pfalzner and her colleagues conducted more than 3,000 simulations, tweaking the different stars and how close by they pass the Solar System observing the results and comparing them to the known eccentric orbits of the TNO clusters. And they found that a star just a little smaller than the Sun, skimming past the outer Solar System, could have produced the higgledy-piggledy shenanigans out there today.

The flyby could even have produced the strange orbits of objects such as 2008 KV42 and 2011 KT19, which orbit in the opposite direction to the planets, at almost perpendicular inclinations. These objects, too, have previously been invoked in studies looking for evidence of Planet Nine.

And, according to the team's simulations, up to 7.2 percent of the original TNO population could have been flung inward, towards the Sun.

"Some of these objects could have been captured by the giant planets as moons," says Simon Portegies Zwart from Leiden University in the Netherlands. "This would explain why the outer planets of our Solar System have two different types of moons."

The study is far from conclusive. There are quite a few reasons why we might not have spotted Planet Nine, including the fact that it's very dim and very far away. And it's also possible that we're not operating with sufficient data – everything that far from the Sun is hard to see, so the data we could have may be a result of selection bias, limited only to what we can see with our current technology.

Nevertheless, the notion of a stellar flyby isn't implausible, and it is rather a tidy solution.

"The beauty of this model lies in its simplicity," Pfalzner says. "It answers several open questions about our Solar System with just a single cause."

The research has been published in two papers, appearing in Nature Astronomy and The Astrophysical Journal Letters.