Our microplastics problem isn't going away. These tiny fragments of plastic pollution have previously shown up in our lungs, in ancient rocks, and in bottled water. A new study reveals the extent to which they're infiltrating the brain, too.

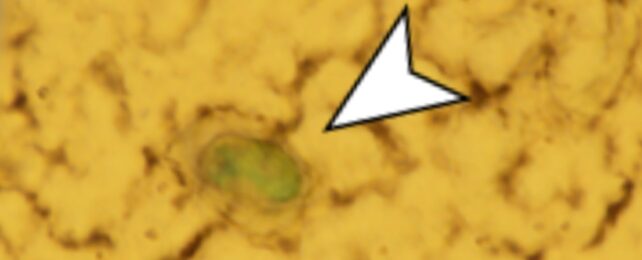

An international team of scientists looked at the olfactory bulbs – the masses of brain tissue that take in smell information from the nose – in 15 deceased humans, and found the presence of microplastics in 8 of them.

Researchers have previously found microplastics in brain blood clots, but this is the first published study to detect the material in actual brain tissue. Another similar piece of research is now undergoing peer review.

"While microplastics have been detected in various human tissues, their presence in the human brain has not been documented, raising important questions about potential neurotoxic effects and the mechanisms by which microplastics might reach brain tissues," write the researchers in their published paper.

The researchers note that particles and fibers were the most common shapes, and polypropylene the most common polymer: it's one of the most widely used plastics, found in everything from packaging to car parts and medical devices. The particle sizes ranged from 5.5 micrometers to 26.4 micrometers, no more a quarter the width of the average human hair.

Previous research found air pollution particles making their way up the olfactory pathway – this latest study suggests microplastics could be using the same route to the brain, through tiny holes in the cribriform plate (just below the olfactory bulb).

"The identification of microplastics in the nose and now in the olfactory bulb, along with the vulnerable anatomical pathways, reinforces the notion that the olfactory pathway is an important entry site for exogenous particles to the brain," write the researchers.

Despite all of these risks and health impacts, we don't seem to be able to cut down on our reliance on plastics. Despite ongoing efforts to produce plastic that's more biodegradable, the fact is that plastic production has doubled in the last 20 years.

What's not clear yet is what damage these microplastics might do to our own health, yet it's a safe bet that increasing concentrations of synthetic material inside the brain isn't good news. Neuron damage and increased risk of neuronal disorders are likely, based on recent research.

There's also the nose connection to consider. A link between air pollution and cognitive problems has already been well-established, and if microplastics are making their way into our nasal passages, that's likely to make matters worse.

"Some neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson's disease, seem to have a connection with nasal abnormalities as initial symptoms," write the researchers.

The research has been published in JAMA Network Open.