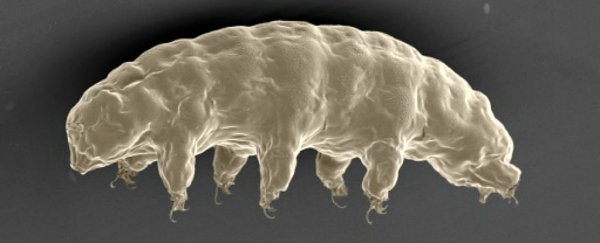

Water bears, or tardigrades as they're officially known, are chubby little anomalies that are damn near indestructible - they can bounce back from total desiccation, endure the greatest temperature extremes we can throw at them, and can even survive the frozen vacuum of space.

Now a team of scientists in Japan has sequenced their genomes, and finally shed some light on how they got so tough. It turns out tardigrades have developed a range of handy tools to help them avoid death time and time again - including a protein that acts as an in-built radiation shield for DNA.

Even cooler, the researchers showed that, when incorporated into human cells, this radiation-blocking protein also reduced the damage to human DNA from X-rays by an impressive 40 percent.

"We were really surprised," one of the researchers, Takuma Hashimoto from the University of Tokyo, told AFP.

"It is striking that a single gene is enough to improve the radiation tolerance of human cultured cells."

The team performed their genetic analysis on a specific species of water bear called Ramazzottius varieornatus, which is arguably the toughest of all tardigrade species.

Among other anomalies, what they found in the tiny creature's genome was a protein called Dsup - short for "damage suppressor" - which suppresses radiation damage, as well as the damage caused by desiccation, which be just as destructive to DNA.

"Tolerance against X-ray is thought to be a side-product of [the] animal's adaption to severe dehydration," lead researcher Takekazu Kunieda, also from the University of Tokyo, told Jason Bittel from Nature.

(An experiment last year showed that water bears can survive being totally dehydrated by turning into glass.)

Because it's so much easier to study the animal's genome within mammalian cells, the researchers manipulated the DNA in human cells to get them to produce pieces of the tardigrade's genome - which is where they noticed that Dsup could also protect human cells.

If Dsup could also be transplanted into live humans, it could make us more resilient to radiation - something that would be extremely useful when we venture out further into space.

According to Ingemar Jönsson from Kristianstad University in Sweden, this makes the new paper "highly interesting for medicine".

In addition to Dsup, the researchers also showed that the tardigrade genome contained 16 copies of anti-oxidant enzymes, while most animals have just 10, and they also have four copies of DNA repair genes - most animal cells only have one.

And the study could also help put to rest a debate that started last year, when a team of scientists sequenced a tardigrade's genome and showed that almost one-sixth of its DNA came from other species - more than any other known animal species.

The researchers suggested that foreign DNA might be able to explain some of water bears' unique properties, but a few weeks later, a separate group of scientists disputed the claim, and showed that the foreign DNA was most likely a result of contamination, not genetic transfer.

The new Japanese study backs up those critics, by finding less than 1.2 percent of the species' DNA to be foreign after carefully purifying the Ramazzottius varieornatus DNA - a very normal amount for most animals.

And while some of the protective genes were imported from other species - such as the antioxidant enzymes - most were "home-grown", Kunieda told Andy Coghlan from New Scientist.

"It lays to rest the proposal that tardigrades acquired their extreme survival biology through massive acquisition of genes from other species," added Mark Blaxter from the University of Edinburgh in the UK.

The fact that water bears are so damn indestructible because of their own adaptations just makes them even cooler in our book - and in the future we might even find out that those protective genes could be useful for humans, too. We just got reminded why these guys are our favourite animals.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.

Oh, and as a bonus, here's a tardigrade walking on moss. You're welcome.