When a baby was born with three biological parents in 2016, there were concerns about the ethics and safety of the procedure.

During the experimental procedure, the mother's nuclear DNA was transplanted into a donor egg with its own nuclear DNA removed. Doctors then fertilized the donor egg with the transplanted nuclear DNA using the husband's sperm.

This procedure was intended to prevent the child from inheriting a rare neurological disease called Leigh syndrome, which can be passed down through the maternal mitochondria.

The concern was that traces of maternal mitochondria extracted during the spindle transfer would multiply, creating health problems for the child.

Spindle transfer involves extracting the spindle-shaped group of chromosomes containing the mother's nuclear DNA from an egg.

However, a study looking at the effect of this procedure on the genetics of individual cells five days after fertilization has found that they are no different from a control group, suggesting that the procedure does not affect embryonic development in its early stages.

The researchers used a single-cell triple omics sequencing method to examine the genome, DNA methylome, and transcriptome for dozens of cells at the blastocyst stage of development.

"Our results suggest that spindle transfer seems generally safe for embryonic development, with a relatively minor delay in the DNA demethylation process at the blastocyst stage," the authors report.

"Mitochondrial replacement therapy is a controversial field," says study co-author Wei Shang, an obstetrician and gynecologist at the Chinese PLA General Hospital in Beijing. "With our research, we hope to provide a foundation for the development of the technique."

Dietrich Egli, a stem-cell biologist at Columbia University, told Nature the study was "unique and fabulous" due to its high-quality data.

"This is the first [study] that has performed such a comprehensive comparison of human embryos that were created with spindle transfer," he said.

The first child conceived using donor mitochondria and the spindle transfer method in 2016 did not have any health issues seven months after birth, but the long-term effects are not yet known.

"The maternal mitochondria and nucleus have coexisted for a long time, so maybe the nucleus may prefer cells with maternal mitochondria," Min Jiang, a mitochondrial biologist at Westlake University in Hangzhou in China, says.

"So far, the studies show spindle transfer works. But the long-term health of children born using the therapy will need to be investigated with clinical trials," she says.

In the 2016 case, less than 5 percent of maternal mitochondrial DNA containing the pathological variant was transferred. Current techniques can reduce that down to 2 percent.

The UK and Australian governments have legalized mitochondrial donation to prevent serious genetic inherited diseases. But it is still banned in the US, and its legality is uncertain in China.

Leigh syndrome is one of a few diseases caused by pathological variants in maternal mitochondria affecting as many as 1 in 5,000 children.

Children with Leigh syndrome usually do not survive past the age of two or three. They lose mental, movement, and swallowing abilities, and experience respiratory difficulties, vomiting, diarrhea, and failure to thrive.

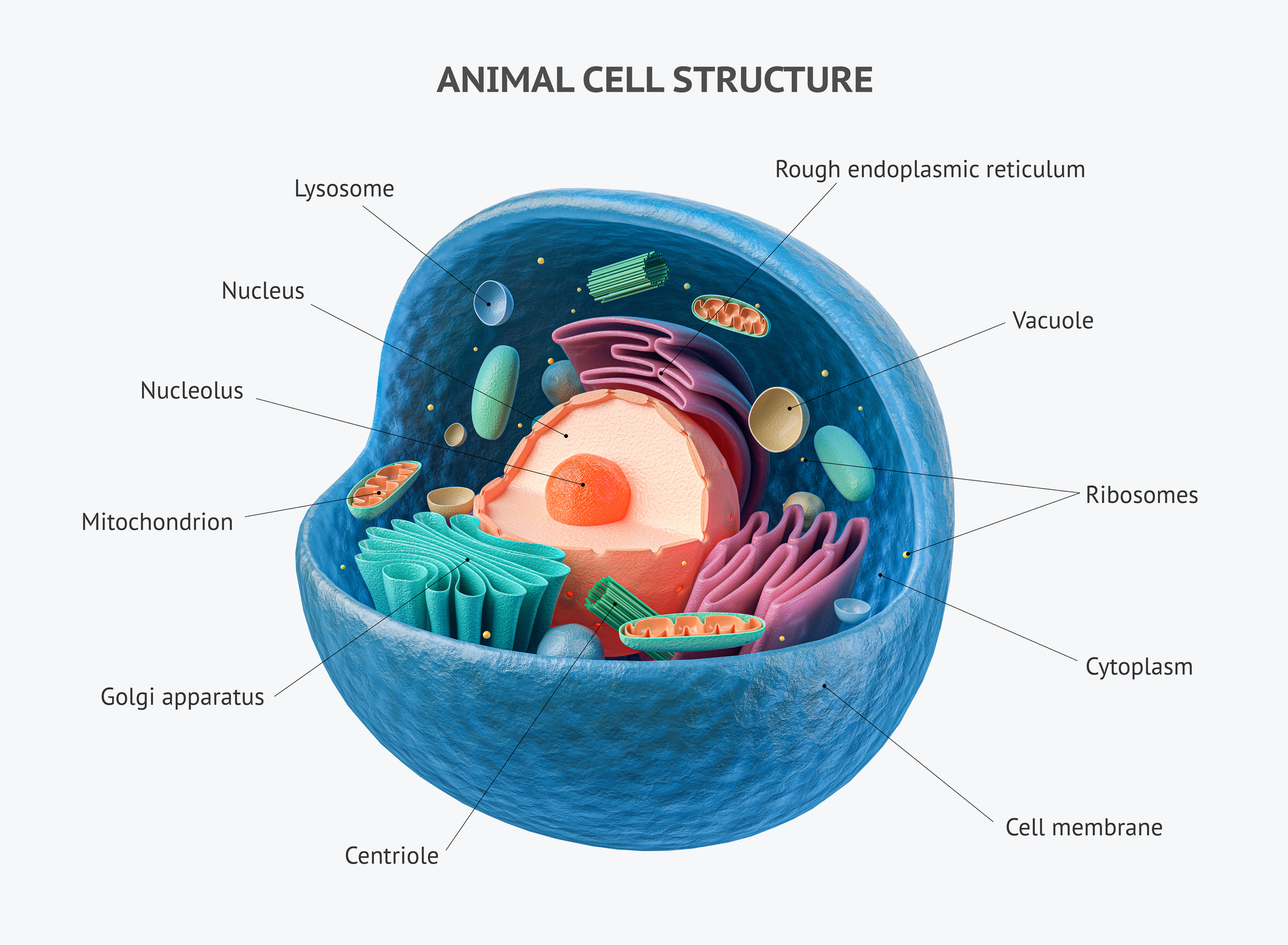

Most DNA in human embryos comes from the nucleus inside the human egg and sperm. But mitochondria, which are the powerhouses of the cell, also contain some DNA. There are up to 25,000 genes in the nucleus and just 37 genes in the mitochondria.

Sperm contains some mitochondrial DNA, but it is destroyed in the fertilization process, and therefore only the mother's mitochondria are left to replicate.

This paper was published in PLOS Biology.