The discovery of a new kind of immune cell receptor could pave the way for a new type of T-cell cancer therapy that can attack a diverse range of cancers in human patients without requiring tailored treatment.

The researchers behind the discovery emphasise that testing is still at an early stage, having been conducted only in mice and in human cells in the lab, not yet in living patients. But the preliminary results are promising, and suggest we could be on the verge of a significant advancement in T-cell therapies.

To understand why, let's backtrack a little on what T-cells are, and what T-cell therapies do, because they're still very much an emerging field of treatment in oncology.

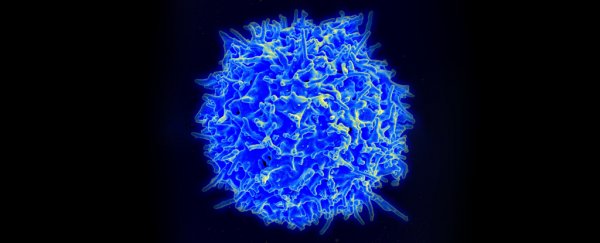

T-cells are a type of white blood cell involved in the function of our immune system. When T-cells are activated by coming into contact with defective or foreign cells in the body, they attack them, helping us fight off infection and disease.

In T-cell therapy – the most common form of which is called CAR-T (for Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells), scientists hijack and augment this natural function of T-cells to steer them towards tumour cells in particular.

In CAR-T treatments, doctors extract T-cells from patients' blood, genetically engineering them in the lab to make them specifically identify and target cancer cells. The edited T-cells are then multiplied in the lab before being administered to patients.

Some of the limitations of the CAR-T technique are that the edited T-cells are only able to recognise a few kinds of cancer, and the entire therapy needs to be personalised for different people because of a T-cell receptor (TCR) called human leukocyte antigen (HLA).

HLA is what enables T-cells to detect cancer cells, but it varies between individuals. And that's where this new discovery comes in.

In the new study, led by scientists at Cardiff University in the UK, researchers used CRISPR–Cas9 screening to discover a new kind of TCR in T-cells: a receptor molecule called MR1.

MR1 functions similarly to HLA in terms of scanning and recognising cancer cells, but one big difference is that, unlike HLA, it doesn't vary in the human population – which means it could potentially form the basis of a T-cell therapy that works for a much broader range of people (in theory, at least).

We're not there yet; but preliminary experiments in the lab involving MR1 are indeed promising, although we need to be aware that the results need to be replicated safely in clinical trials before we can confirm this is a treatment suitable for humans.

In lab tests using human cells, the MR1-equipped T-cells "killed the multiple cancer cell lines tested (lung, melanoma, leukaemia, colon, breast, prostate, bone and ovarian) that did not share a common HLA," the authors write in their paper.

Tests upon mice with leukaemia – in which the animals were injected with the MR1 cells – revealed evidence of cancer regression, and led to the mice living longer than controls.

Right now, we don't yet know how many types of cancers a technique based on this receptor might treat. That said, the early results certainly suggest a diverse range could be susceptible, according to the study.

If these sorts of effects can be replicated in humans – something the scientists hope to begin testing as early as this year – we could be looking at a bright new future for T-cell treatments, experts say.

"This research represents a new way of targeting cancer cells that is really quite exciting, although much more research is needed to understand precisely how it works," says research and policy director Alasdair Rankin from blood cancer charity Bloodwise, who was not involved in the research.

To that end, the next step for the team – in addition to organising future clinical trials – will be learning more about the mechanisms that enable MR1 to identify cancer cells at a molecular level.

There's a lot more to learn here before we can truly proclaim this is some kind of universal cancer treatment, but there certainly look to be some exciting discoveries on the horizon.

"Cancer-targeting via MR1-restricted T-cells is an exciting new frontier," says senior researcher and cancer immunotherapy specialist Andrew Sewell.

"It raises the prospect of .. a single type of T-cell that could be capable of destroying many different types of cancers across the population. Previously nobody believed this could be possible."

The findings are reported in Nature Immunology.