One of the scariest parts of a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease can be not knowing what's going to happen next, both for patients and carers – but a new study has offered hope for demystifying the prognosis.

A team of experts has developed a tool that can forecast the next five years of cognitive decline for patients with early signs of Alzheimer's.

The course of dementia can vary between people, but the researchers were able to sketch out a predictive model based on a careful study of actual patients.

"People are very interested in what to expect from the disease in themselves or their loved ones, so better prediction models are urgently needed," explains physician-researcher Pieter van der Veere of Amsterdam University in the Netherlands.

Van der Veere and his colleagues studied 961 patients, with an average age of 65 years, 651 with mild dementia and 310 with mild cognitive impairment. Each patient also had amyloid beta plaques, protein deposits in their brain that are characteristic of Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of dementia.

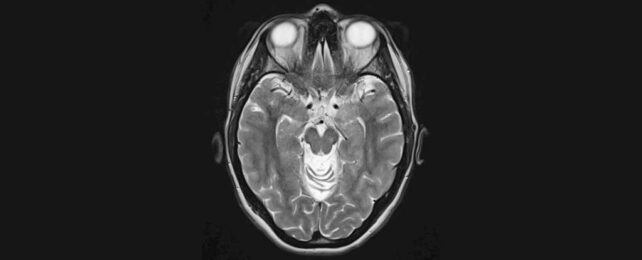

They carefully analyzed MRI scans and biomarkers collected from cerebrospinal fluid. They also took into account the age and gender of each patient, medical history, and cognitive test scores over time, marked out of 30.

A test score over 25 indicated no dementia; 21 to 24 was mild dementia; 10 to 20 was moderate; and anything below 10 was considered severe dementia.

The test scores showed that, on average, patients with mild cognitive impairment started with a score of 26.4, declining to 21 after five years. But patients with mild dementia dropped from 22.4 to 7.8 in five years, a much faster progression.

The researchers were also able to model the effects of medication.

"In the future, this will become even more important if we can treat Alzheimer's disease," says neuroscientist Wiesje van der Flier of Amsterdam University.

"This can be a starting point for conversations between doctor, patient and family about the pros and cons of treatments, so that they can come to an appropriate decision together."

According to the models, a patient with mild cognitive impairment and a baseline cognitive test score of 28 could reach moderate impairment after six years. By taking medication that reduces the rate of decline by 30 percent, reaching the point of moderate impairment would take 8.6 years.

For a patient with mild dementia and a starting score of 21, reaching moderate impairment would take 2.3 years, or 3.3 years if slowed with medication.

The actual scores can vary quite a bit: only half the patients with cognitive impairment had scores within two points of the prediction, and half the dementia patients were within three points. This suggests that, although the models can help inform patients about cognitive decline, a confident prognosis can be challenging to reach.

However, the findings show promise. By including as many parameters as possible, the model can produce a tailored result that can give patients and loved ones more of an idea about what to expect as the disease progresses, as long as medical practitioners are clear about the lack of certainty.

Meanwhile, the scientists hope they will be able to refine their research to produce better prediction models in the future.

"We understand that people with cognitive problems and their care partners are most interested in answers to questions like 'How long can I drive a car?' or 'How long can I keep doing my hobby?'" Van der Veere says.

"In the future, we hope that models will help make predictions about these questions about quality of life and daily functioning. But until then, we hope these models will help physicians translate these predicted scores into answers for people's questions."

The research has been published in Neurology.