Meeting the world's data storage demands is costly, in terms of money, energy, and environmental impact – but a new material could significantly improve the cooling of our data centers while also making our home and business electronics more energy efficient.

Currently, bulky and energy-intensive cooling solutions are typically deployed to chill out the hardware holding our data, adding up to about 40 percent of overall data center energy use (around 8 terawatt-hours every year).

The team from the University of Texas at Austin and Sichuan University in China estimates around 13 percent of those 8 terawatt-hours could be shaved off by their new organic thermal interface material (TIM).

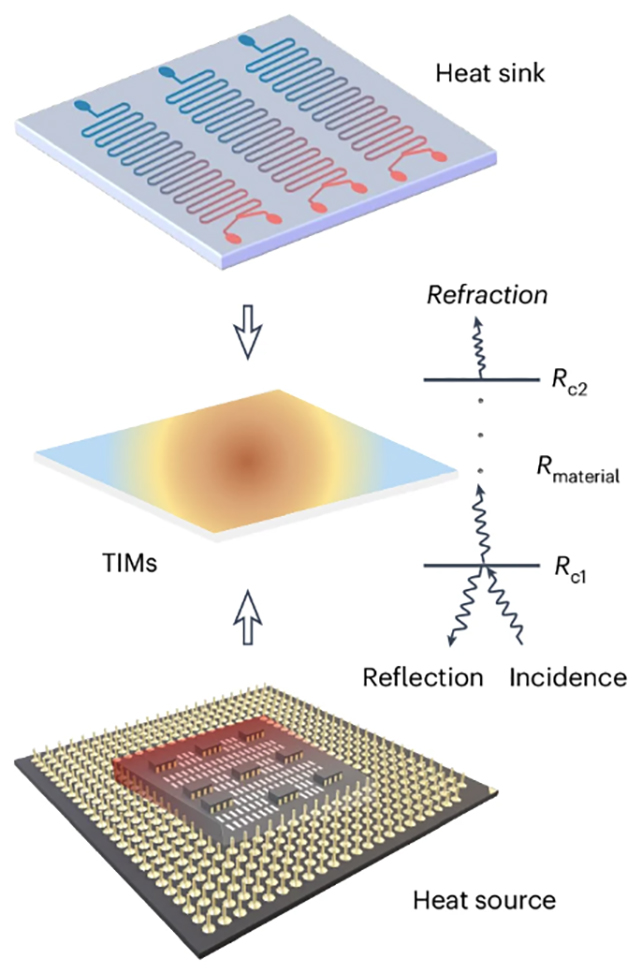

The TIM substantially boosts the rate at which heat can be taken away from active electronic components and channeled into a heatsink for air or water to carry away.

That in turn means a lower demand on active cooling technologies, including fans and liquid cooling.

"The power consumption of cooling infrastructure for energy-intensive data centers and other large electronic systems is skyrocketing," says materials scientist Guihua Yu, from the University of Texas at Austin.

"That trend isn't dissipating anytime soon, so it's critical to develop new ways, like the material we've created, for efficient and sustainable cooling of devices operating at kilowatt levels and even higher power."

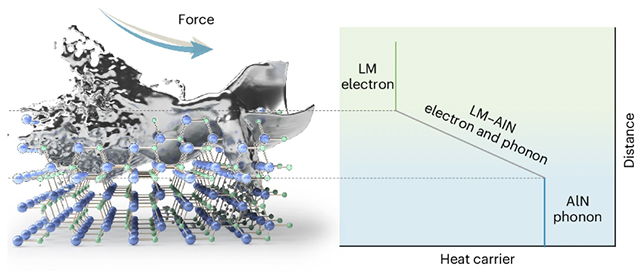

The TIM developed here is a colloidal mixture of the liquid metal galinstan and particles of aluminum nitride, combined in a way that creates a gradient interface – one that helps heat pass through without any hard boundaries between the two substances.

In an experimental lab test setup, the TIM was able to double the amount of heat that could be safely transferred away from every square centimeter of an electronic component, compared to a leading thermal paste – while also reducing the component's overall temperature.

The setup used a cooling pump, which is a common protection against overheating, and the TIM cut the energy use of the pump by 65 percent. This was only a small-scale example, but it shows the heat-transferring potential of the material.

"This breakthrough brings us closer to achieving the ideal performance predicted by theory, enabling more sustainable cooling solutions for high-power electronics," says Kai Wu, from Sichuan University.

The next step is to get the material working on larger systems and in a wider variety of scenarios, something the researchers are already in the process of doing by partnering up with data center providers.

Analysts expect data center electricity usage in 2028 to be double what it was in 2023, driven largely by the increasing demands of artificial intelligence models. That presents a real energy demand problem – one that scientists are working hard to solve.

"Our material can enable sustainable cooling in energy-intensive applications, from data centers to aerospace, paving the way for more efficient and eco-friendly technologies," says Wu.

The research has been published in Nature Nanotechnology.