Using a combination of two drugs, scientists have managed to shrink - and even eliminate - a specific type of breast cancer tumour in as little as just 11 days.

The results were reported at the European Breast Cancer Conference in Amsterdam, which means they're yet to be peer-reviewed, but if they hold up to scrutiny, the finding suggests that, for some women, the new treatment could replace the need for chemotherapy altogether.

The combination of drugs targeted the HER2 protein, which is found in around one in 10 breast cancers, and is known to make tumours particularly aggressive and resistant to treatment.

The results are so incredible because the researchers weren't even trying to shrink the tumours in the first place. They were simply investigating the benefits of giving women drugs in the short window between a tumour being diagnosed and surgically removed. But by the time the patients were ready to undergo surgery, the tumours had already disappeared in some patients, taking just 11 days to shrink away.

"We were particularly surprised by these findings as this was a short-term trial," one of the lead researchers, Judith Bliss from the Institute of Cancer Research in London, told the BBC. "It became apparent some had a complete response. It's absolutely intriguing, it is so fast."

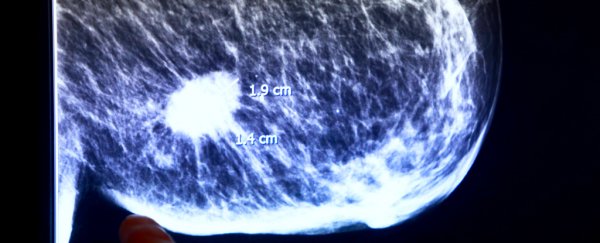

The experiment was conducted with 257 women who had been diagnosed with HER2-positive breast cancer between 1 and 3 cm in size. Out of those participants, 66 received the combination of the two drugs, and in less than two weeks, 11 percent of them saw their tumours disappear entirely. Only 17 percent had tumours less than 5 mm in size left.

"We hope this particularly impressive combination trial will serve as a stepping stone to an era of more personalised treatment for HER2 positive breast cancer," said Delyth Morgan,Delyth Morgan, chief executive at Breast Cancer Care. "Such a rapid response to treatment could soon give doctors the unprecedented ability to identify women responding so well that they would not need gruelling chemotherapy."

The drugs are lapatinib and trastuzumab, which is also known as Herceptin. Both are known to target HER2 already - in fact, the standard treatment for HER2-positive breast cancer involves surgery, followed by chemo and Herceptin. But while Herceptin targets the surface of cancer cells, lapatinib is able to penetrate the cells and attack from within.

More studies will now need to be done on the long-term benefits of the treatment before researchers can start recommending it to patients - particularly seeing as HER2-positive breast cancer has such a high risk of coming back.

"We would have to be very clear we're not taking a backwards step and increasing the risk of relapse," said Bliss.

But the medical community is getting cautiously excited for what this could mean. "These results are very promising if they stand up in the long run and could be the starting step of finding a new way to treat HER2 positive breast cancers," said Arnie Purushotham from Cancer Research UK.