Hermit crabs are well known for their ability to turn an empty shell into protective armour, but it seems that shells aren't the only armour around.

A new species of hermit crab that shelters in solitary corals has been discovered in southern Japan.

Details of the discovery, made by scientists at Kyoto University, have just been published in the journal PLOS ONE.

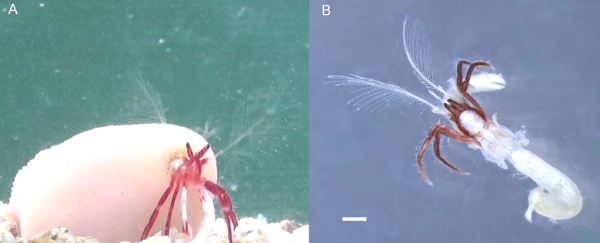

With bright red legs and brilliant white claws, the adult crab is just a few millimetres across but is capable of carrying coral bodies that are far larger.

Named after the coral it carries, Diogenes heteropsammicola has a lot to gain from having a coral for a home.

Throughout their lives most hermit crabs shift from shell to shell to get a better fit, competing with other crabs to get the best deal.

But for this particular species, there is no need. Its body sits safely curled up inside a cavity in the coral – a space that grows with the crab, so it never needs to find a new shelter.

To add to that, the coral comes with a sting, protecting the crab from would-be predators, like starfish, larger crabs and octopus.

The crab certainly gets a good deal here, but what of the coral?

Not all corals are the reef-building kind. Solitary corals, like those inhabited by these crabs, are often found on shallow sandy seabeds.

Such a lifestyle comes with the risk of being buried by sediment and overturned by strong currents.

To combat this, some (known as walking corals) have evolved an incredible partnership with other creatures to shift them out of the sand and on to pastures new.

Walking corals literally use other species to do their walking for them.

Until now, the key coral-shifting creatures we knew about were "sipunculans" – a type of marine worm that, in exchange for accommodation, would shuffle corals across the seafloor.

Relationships like this are known as symbiotic and each partner, accordingly, is known to science as a symbiont.

It is very unusual for a symbiotic relationship to change and – if it does – the new partner is usually from a closely related species.

This is because both symbionts are heavily dependent on each other. They are also highly specialised, which makes working with another partner difficult.

But hermit crabs have now been found inhabiting some of the corals in the Amami Islands, part of a chain that stretches southwards from Japan towards Taiwan.

The crabs filled the exact same cavity often occupied by worms. They filled the same role: walking the coral out of trouble, and they even received the same shelter benefits in return.

So how did this come about?

I contacted Momoko Igawa, one of the scientists who made the discovery while surveying corals in the Amami and Okinawa Islands.

She told me that typically a young coral first settles on a small shell that has already been colonised by a sipunculan.

"The coral then grows over and ultimately beyond the shell, providing a coiled cavity for the equally growing worm partner," she explained.

It seems likely that a similar process led to hermit crabs inhabiting the corals.

![]() The corals provide shelter for the hermit crabs, protecting them from predators.

The corals provide shelter for the hermit crabs, protecting them from predators.

In turn, the crab transports the coral about the sea floor, rescuing it when overturned by strong currents and stopping it from getting stuck in a sediment overload.

As Igawa points out, these are mysterious animals with a remarkable evolutionary history.

Sara Mynott, PhD researcher in Marine Ecology, University of Exeter.

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Read the original article.