Gabriela experienced the painful joint inflammation and draining fatigue that was her own immune system turning against her at an early age. Presenting with scarily high blood pressure and a leaky heart valve, the young Spanish patient was diagnosed with a severe case of lupus when she was only seven years old.

Now Gabriela's genome may have revealed an important clue to this potentially fatal and incurable disease that impacts around 5 million people worldwide.

Symptoms vary significantly among – and even within – patients, as the immune system can start attacking any part of the body. This makes lupus challenging to diagnose.

Symptoms can include different degrees of rashes, fevers, fatigue, joint pains, anemia, and kidney and other organ problems.

"It has been a huge challenge to find effective treatments for lupus; current treatments are predominantly immune-suppressors, which work by dialing down the immune system to alleviate symptoms," says ANU immunologist Carola Vinuesa.

Suppressing immune systems comes with all sorts of potentially debilitating side effects.

"Gabriela presented as an interesting case due to her early lupus diagnosis, meaning there was likely a greater genetic contribution to her lupus development," immunologist Grant Brown from Australian National University (ANU) told New Scientist.

Brown and colleagues identified a gene in question, TLR7, in Gabriela's X chromosome, which may explain why this disease impacts nine times as many women as men.

"This means females with an overactive TLR7 gene can have two functioning copies, potentially doubling the harm," explains Vinuesa, whereas men can only get one copy of this gene on their one X chromosome.

When genes go wrong, it often means they or the thing they code for broke down and can no longer achieve their purpose. However, by some wild fluke, a genetic mutation can get the gene or its product to start doing something too well or something entirely new instead. Known as a gain-of-function mutation, this can really throw a spanner in our finely tuned biological circuitry.

The TLR7 gene codes for a protein that should be on the prowl for viral RNA – detecting it by binding to guanosine (in a particular configuration or concentration) and then calling in the cavalry of immune cells to deal with the invader.

But Gabriela's mutated version of TLR7 gained the ability to be hypersensitive to guanosine, so it binds to much smaller traces of the RNA-associated molecule or the molecule in different configurations than it would normally.

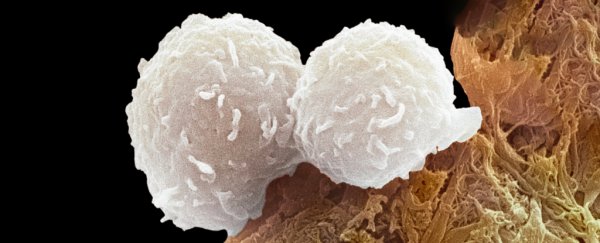

This, through a circuit of cell signaling, led to an accumulation of the immune system's B cells; these traitorous cells then attacked Gabriela's tissues.

To confirm the TLR7 gene mutation does indeed cause lupus, the team genetically engineered the gene into mice, who developed lupus-like symptoms. Gabriela, now a teenager, named the new mouse model 'kika'.

Further tests in kika mice allowed the team to understand the faulty immune cell summoning circuit.

"These results suggest that hypersensitive TLR7 signaling enables the survival of B cells that bind to self-antigen through their surface B cell receptor," Brown and team wrote in their paper.

Previous studies in mice have shown duplicating TLR7 increases autoimmunity, and deleting it prevents or fixes the genes in mice with lupus. However, mutations in this gene have only been discovered in two other lupus patients so far, suggesting different parts of the B cell signaling circuit that TLR7 initiates may be causing the problems in other people with lupus.

"While it may only be a small number of people with lupus who have variants in TLR7 itself, we do know that many patients have signs of overactivity in the TLR7 pathway," explains Nan Shen, co-director of China Australia Centre of Personalised Immunology. "By confirming a causal link between the gene mutation and the disease, we can start to search for more effective treatments."

The researchers are working with pharmaceutical companies to explore treatments that target the faulty gene and the protein it codes for.

"There are other systemic autoimmune diseases, like rheumatoid arthritis and dermatomyositis, which fit within the same broad family as lupus," says Vinuesa. "TLR7 may also play a role in these conditions."

"I hope this finding will give hope to people with lupus and make them feel they are not alone in fighting this battle," says Gabriela. "Hopefully, the research can continue and end up in a specific treatment that can benefit so many lupus warriors who suffer from this disease."

This research was published in Nature.