Jacques Dubochet, Joachim Frank and Richard Henderson have won the Nobel Prize in chemistry "for developing cryo-electron microscopy for the high-resolution structure determination of biomolecules in solution," the Nobel committee announced Wednesday.

Cryo-electron microscopy is "a cool method for imaging the materials of life," said Nobel committee member Göran K. Hansson from Stockholm. The development allows scientists to visualise proteins and other biological molecules at the atomic level.

Dubochet, a Swiss citizen, is a professor at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland. Joachim Frank, born in Germany, is a Columbia University professor in New York. Richard Henderson, of Scotland, works at Cambridge University in Britain.

Scientists must keep molecules in place to take images in ultra-high resolution. Other microscopic techniques, such as x-ray crystallography, are far more rigid than cryo-electron microscopy.

Stockholm University biochemist Peter Brzezinski said on Wednesday that the future of cryo-electron imaging will not be simply taking still images but those of molecules in motion, recording movies that illuminate a world on the atomic scale.

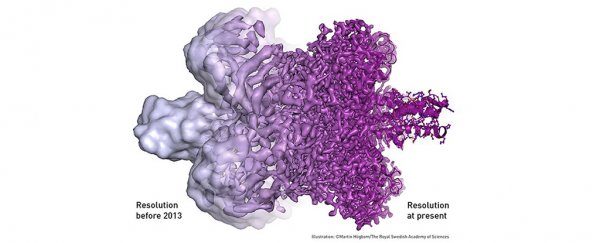

The final technical hurdle was overcome in 2013, when a new type of electron detector came into use. pic.twitter.com/Ue9c0R6v7y

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 4, 2017

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has awarded 109 prizes in chemistry. Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff, a pioneer in physical chemistry, won the inaugural award in 1901.

Last year, the Nobel committee recognised three chemists who created truly micro machines: engines just a few molecules in size. The researchers defeated molecular equilibrium to design shapes that, like microscopic wheels, move on command.

For this year's award, some Nobel prognosticators gave the nod to John B. Goodenough, 94, inventor of the lithium-ion battery.

Gene-editing system CRISPR-Cas9, too, has been an oft-cited contender during the Nobel award season.

Microbes evolved CRISPR to defend against viruses. Scientists have wielded CRISPR as a tool to shape organisms' genes, demonstrating what a few researchers say is its Nobel-worthy potential.

In one recent study, biologists grew butterflies with strange new wing colours. Others created the first mutant ants. Geneticists implanted a black-and-white movie in E. coli bacteria, using CRISPR to store pixels as DNA snippets.

But contention over who should get primary credit for the work - a patent dispute that pits MIT and Harvard's Broad Institute against the University of California, Berkeley - may be keeping CRISPR from being awarded a Nobel, bound as the committee is by its rule that only three winners can share the prize.

The Nobel Prize in literature will be announced on Thursday, followed by the peace prize on Friday. An award in economics, not one of the original prizes but now conducted in memory of Alfred Nobel, will be announced Monday.

2017 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.