Archaeologists excavating a vast and ancient "city of the dead" in Africa have recovered the largest collection of texts in the mysterious language of the Kushites. Dating back to 2,700 years ago, the find includes extraordinary tablets commemorating the dead.

The items hail from a site called Sedeinga in Sudan, known for the ruins of a temple dedicated to the 14th century BCE Egyptian queen Tiye, the grandmother of Tutankhamun.

But between the 7th century BCE and the 4th century CE, the site was a significant necropolis - city of the dead - for the kingdoms of Napata and Meroe, which mixed Egyptian traditions with their own.

Combined, the two kingdoms were known as the kingdom of Kush by their Egyptian neighbours.

Very little information remains about these cultures, but funerary items can tell us a lot. Although much of the necropolis is in ruins, it is large - containing the remains of at least 80 brick pyramids and 100 tombs.

It is from these tombs that the artefacts were recovered by a research team led by the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the French Archaeological Unit Sudan Antiquities Service (SFDAS).

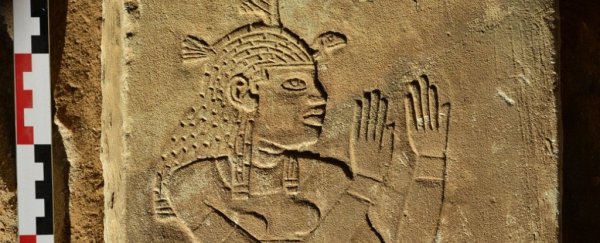

The Maat lintel. (Vincent Francigny/Sedeinga archaeological mission)

The Maat lintel. (Vincent Francigny/Sedeinga archaeological mission)

The tombs, lintels and steles - a type of tablet stone used as a commemorative monument - represent the largest collection of texts in Meroitic.

It's the earliest known written language of sub-Saharan Africa, written in characters borrowed from the ancient Egyptians - at least some of whom, genomic data suggests, were more closely related to the people of the Near East than middle Africa.

"The Meroitic writing system, the oldest of the sub-Saharan region, still mostly resists our understanding," Vincent Francigny, an archaeologist with the SFDAS and co-director of the excavation, told Live Science.

"While funerary texts, with very few variations, are quite well-known and can be almost completely translated, other categories of texts often remain obscure. In this context, every new text matters, as they can shed light on something new."

Most of the tombs and pyramids date back to the earlier Napata kingdom, the archaeologists found. Five centuries later, the Meroitics added new structures to these earlier buildings - chapels of brick and sandstone on the pyramids' western walls, built for the worship of the dead.

The stele dedicated to Lady Meliwarase. (Vincent Francigny/Sedeinga archaeological mission)

The stele dedicated to Lady Meliwarase. (Vincent Francigny/Sedeinga archaeological mission)

One significant find was a chapel lintel depicting Maat, the Egyptian goddess of law, balance, order, harmony, peace and justice. It dates from the 2nd century CE, and is the first known extant representation of the goddess that shows her with African features.

They also found two commemorative texts dedicated to women of high rank.

Maliwarase of Nubia, we know from her stele, was sister to two grand priests of the Sun god Amon, and mother to the governor of Faras, a city on the second cataract of the Nile.

Adatalabe was described in four lines on the lintel of a sepulchre. She was related to a prince of the reigning family of Meroe.

The lintel describing Lady Adatalabe. (Vincent Francigny/Sedeinga archaeological mission)

The lintel describing Lady Adatalabe. (Vincent Francigny/Sedeinga archaeological mission)

The fact that both items describe women is not a stroke of luck.

There is strong evidence to suggest that, unlike the Egyptians, the Nubian people were matrilineal, or at least that women were held in very high esteem. They may have borrowed from other cultures, but their identity was their own.

"Meroe was a kingdom where, among others, some Egyptian cultural and religious concepts were borrowed and adapted to local traditions," Francigny said.

"We should not see Meroe as a passive recipient for foreign influences - instead, Meroites were very selective about what they could borrow to serve the purpose of the royal family and the development of their pharaonic, but non-Egyptian, society."

Work on the site is ongoing, and is planned to continue until 2020.

Editor's note (17 Apr 2018): This article has been updated to clarify that genomic evidence shows some ancient Egyptians - but possibly not all - were more closely related to the people of the Near East.