We can all agree that eating well is important for our health. But surely it's acceptable to treat yourself to an unhealthy meal or two on weekends?

A study by researchers from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Australia suggested a diet pattern of 'clean' eating interspersed with 'cheat' meals of junk food could not only lead to weight gain, but affect brain function and gut health in rodents.

Rats that ate a mostly healthy diet but occasionally feasted on high-sugar and saturated-fat foods showed significant cognitive impairment, especially in tests of spatial memory, and negative changes in gut bacteria.

"We think this sort of work is critical to get us to think about maintaining the health of our brain into old age," explains neuroscientist Margaret Morris from UNSW.

The study expands on prior research by members of the team which found an association between poor diet and impaired long-term spatial memory, providing new information on the effects of 'diet cycling'.

Sometimes viewed as a compromise between extremes of healthy and unhealthy eating, the swings in nutrition might come at a cost.

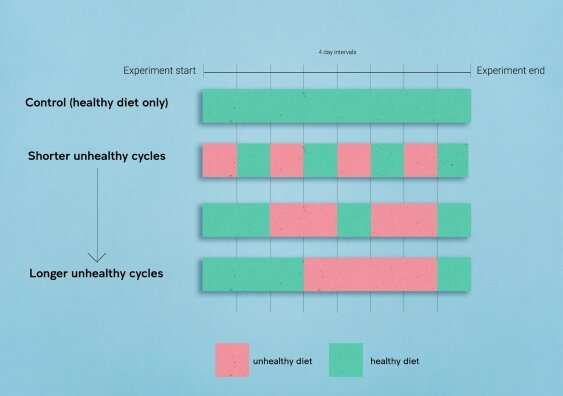

In each of 3 different experiments, a healthy control group of 12 rats were fed standard rat food, and compared to 3 experimental groups of 12 rats who were also sometimes fed processed food high in fat and sugar.

The experimental groups spent the same total number of days being fed unhealthy food, either consecutively or spread across different length 'cycles'.

Before and after the diet cycling periods, the researchers tested the rats' short-term memory and measured the microbiota in their feces. They also weighed them before and after and kept track of how much of each food type the rats consumed.

Rats who ate poorly for any length of time had a less diverse gut microbiome, with more bacteria linked to obesity and fewer strains of good bacteria linked to weight control. With longer exposure to an unhealthy diet, these changes got worse.

Cognitive impairment also became more severe over time, with the rats that had been fed an unhealthy diet for multiple days performing the worst on memory tests requiring the recall of object placement.

"Our analyses indicated that the levels of two bacteria correlated with the extent of the memory impairment," says Mike Kendig, a medical scientist at UNSW at the time. "This suggests a link between the effects of diet cycling on cognition and the microbiota."

Not surprisingly, the rats who ate a high-fat, high-sugar diet for a long time gained more weight than the rats in the control group. But the length of bad eating cycles didn't seem to affect weight gain directly.

This indicates that the effects on gut and memory health may not be related to the weight gain that is usually caused by an unhealthy diet.

"In humans we know that a diet that increases inflammation appears to be less beneficial for our brain function," says Morris. "And in the past, we've shown in rats that these cognitive deficits actually correlate with inflammation in the brain."

These results add to the growing body of evidence that links gut health, and diet, to brain health.

"We know the gut is very connected to our brain," Morris adds. "Changes to the microbiome in response to our diet might impact our brain and behavior."

While these findings may not be what we want to hear, the scientists emphasize that keeping up healthy eating for a longer period of time appears to yield more favorable outcomes for both gut and brain health.

Other studies suggest good nutrition reduces disease risk and could add years to your life, so it might be worth swapping high fat and sugary treats for healthier options.

"If we can maintain a healthy diet – such as the Mediterranean-type diet with high diversity, fruits, vegetables, low saturated fats, good proteins – we have a better chance of preserving our cognition," Morris concludes.

The study has been published in Molecular Nutrition & Food Research.