Palaeontologists have found what could well be the oldest example of a fossilised eye the world has ever seen, preserved for over half a billion years.

It belongs to a trilobite - a class of once-abundant early arthropods that peaked in the Cambrian Period and thrived in the world's oceans for over 270 million years.

These days we think of the squat, three-lobed sea creatures as the distant ancestors of modern crabs and spiders, and fossil records have shown that these incredibly successful animals were among the earliest beings on Earth to possess a sense of vision.

In fact, they sported a type of compound eye - the optical organ crammed full of vision cells we still see today in flies, bees, and many other arthropods.

But even though researchers have seen evidence of compound eyes in Cambrian trilobite fossils before, the internal structure and function of these proto-eyes remained a mystery.

Now researchers from Estonia, Germany, and Scotland have described a truly exceptional find - a 530-million-year-old trilobite so well preserved, they were able to discern its compound eye at a cellular level.

"The trilobite to which [the eye] belongs is found in a zone where the first complete organisms appear in the fossil record; thus, it is probably the oldest record of a visual system that ever will be available," the team writes in the study.

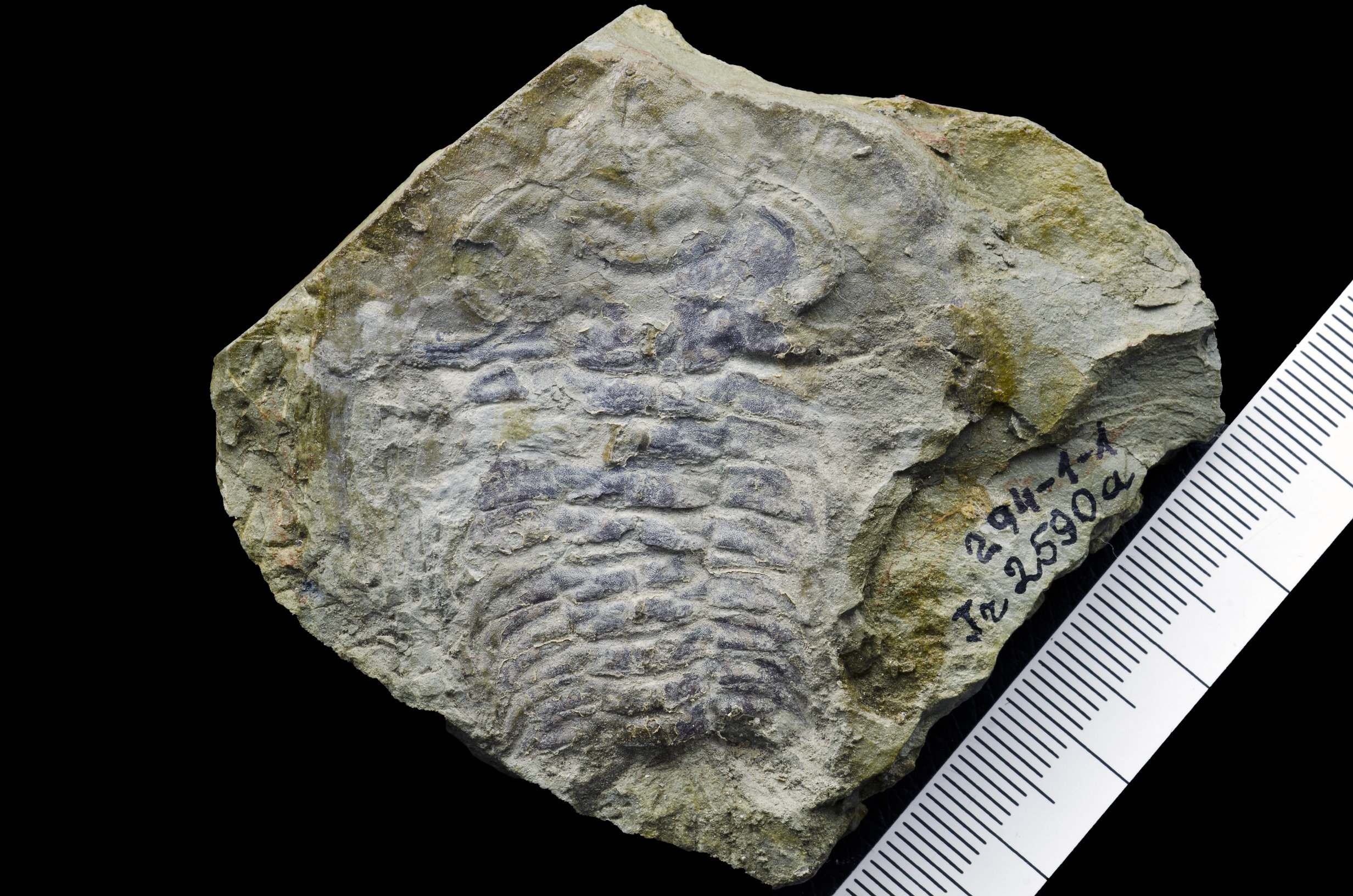

The remarkably preserved fossil, belonging to a species called Schmidtiellus reetae, was collected in Saviranna in northern Estonia.

Due to the local geological conditions during the lower Cambrian era, trilobite fossils collected there are known for exceptionally well-preserved exoskeletons - a feature that is often lost in finds from other parts of the world.

In this case, the trilobite fossil's eye was partially worn away, revealing the internal structure in astounding detail.

(Gennadi Baranov)

(Gennadi Baranov)

The units that make up any modern insect's compound eye are called ommatidia, and the researchers counted about 100 of these in the fossil. Unlike the closely packed modern bug eyes, these cells were more spaced out.

Additionally, the researchers couldn't find much of a lens structure, which they say is remarkable.

"There are indications of round lens-like discs when the eye is studied from the outside, but from the internal aspect, no convexities that could effectuate any refraction of light can be made out," the team writes.

One reason for this could be that the trilobite exoskeletons didn't have the materials in their shells needed to form a lens that could refract light in the marine environments they lived in.

"This exceptional fossil shows us how early animals saw the world around them hundreds of millions of years ago," says one of the team, palaeontologist Euan Clarkson from the University of Edinburgh.

"Remarkably, it also reveals that the structure and function of compound eyes has barely changed in half a billion years."

Indeed, it's crazy to think that scientists can dig up the remains of a creature that's been dead for over 500 million years and find that it had basically the same visual organs as many animals we share the planet with today.

The trilobites didn't quite have the visual acuity of a modern bee, but they saw well enough to avoid obstacles and even avoid their terrifying contemporary predators.

In fact, this early arms race is thought to have contributed to the evolution of increasingly useful eyesight in those primeval oceans.

"The 'race' between predator and prey and the need 'to see' and 'to be seen' or 'not to be seen' were drivers for the origin and subsequent evolution of efficient visual systems, as well as for protective shells," the team writes in the study.

"In its principal structure, it was simpler than, but otherwise almost identical to, that of the modern compound eyes of bees and dragonflies living today."

The finding has been described in PNAS.