Bones found on the remote Arctic island of Spitsbergen suggest the ancient marine reptiles known as ichthyosaurs roamed Earth's oceans for much longer than we thought.

Dated to 250 million years ago, the remains represent the oldest evidence of ichthyosaurs we've ever seen. Moreover, the species represented by the bones was already large and well-adapted to marine life – at a time before the ichthyosaur form was thought to have emerged into the world.

This suggests that our timeline for ichthyosaurs might need to be reconsidered. They may have appeared prior to the End-Permian Mass Extinction that took place 251.9 million years ago, rather than evolving as a result of the event as has been suggested.

"These pioneering seagoing tetrapods," write a team of paleontologists led by Benjamin Kear of Uppsala University in Sweden, "can now be feasibly recast as mass extinction survivors instead of ecological successors within the earliest Mesozoic marine predator communities."

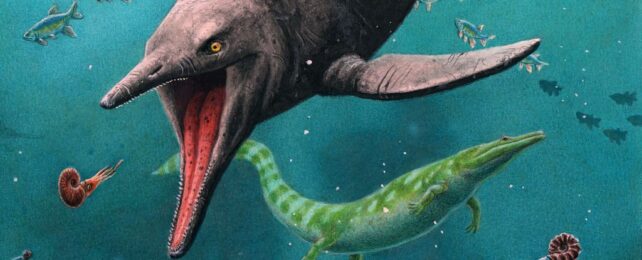

Ichthyosaurs were a group of animals that strongly resembled modern dolphins, if dolphins were giant aquatic lizards instead of mammals. They evolved from land-dwelling creatures that returned to the sea in the Early Triassic, thriving until the Late Cretaceous when a changing climate and slowness to adapt brought their time to an end around 95 million years ago.

In spite of their terrestrial origins, the reptiles quickly adapted to life in the water: their legs turned to fins, their snouts elongated and filled with fish-snatching teeth, and their bones became spongy like those of modern cetaceans.

Fortunately for us, the fossil record is rich with ichthyosaur remains, providing paleontologists with a wealth of information to trace their timeline. That record had previously suggested that ichthyosaurs emerged after the End-Permian Mass Extinction, around 249 million years ago.

The emergence of new forms and functions isn't unexpected in the wake of a mass extinction. Ecological niches empty, leaving surviving organisms a chance to change and occupy them. For a while, ichthyosaurs were among the most efficient predators swimming the world's oceans.

A rocky outcrop on Spitsbergen, however, could upend this origin story. There, in the valley known as Flowerdalen, erosion has carved into the mountains to uncover rock that was a seabed millions of years ago, complete with a fossilized catalogue of the creatures that lived there – amphibians, coelacanths, sharks, and fish.

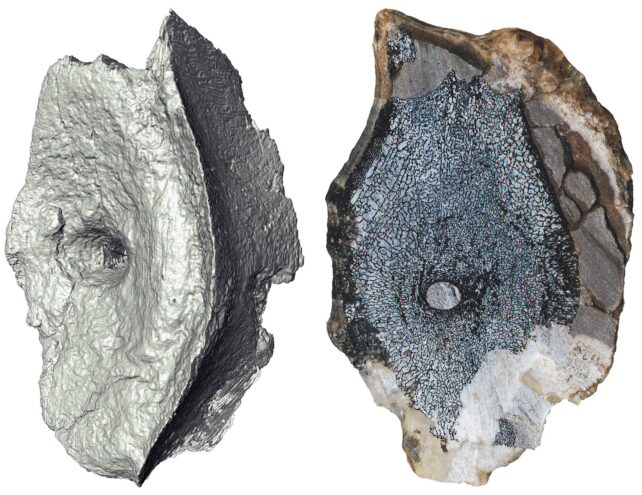

In 2014, paleontologists dug out several items of interest and shipped them to Uppsala University for identification and analysis. Among them were items that no one expected to see in 250 million-year-old fossil beds: 11 articulated tail vertebrae from an adult ichthyosaur.

Not some early progenitor 'prototype ichthyosaur' specimen either. The fossils resembled the bones of ichthyosaurs that came much later in history, complete with a spongy marine tetrapod composition. They also indicated that the animal was quite large and well-formed.

In other words, it was already fully adapted to life as a marine reptile within 2 million years of the final days of the End-Permian Mass Extinction. Given marine reptiles were thought to take between 1.7 and 17.7 million years to diverge, ichthyosaurs may have infiltrated the world's oceans long before the largest exinction event in Earth's history. Once the End-Permian Mass Extinction wiped out an estimated 81 percent of the planet's marine species, ichthyosaurs were already prepared to take over.

"We propose that these preludial marine reptiles most likely evolved before the End-Permian Mass Extinction," the researchers write, "but underwent opportunistic trophic niche diversification and ecological differentiation into shallower water amphibian-dominated versus deeper water ichthyopterygian-dominated habitats during the nascent dispersal of oceanic tetrapods in the earliest Triassic."

Paleontologists will now be searching Spitsbergen and elsewhere to see if they can find more evidence for this revised ichthyosaur timeline.

The discovery has been detailed in Current Biology.