How Neanderthals went extinct while humans survived is one of the biggest questions in our species' history. Researchers have long wondered if our closest extinct relatives might have succumbed to viral infections that plague modern humans today.

That thinly evidenced theory, first proposed in 2010, has become a little more plausible with the discovery of ancient DNA from three viruses found in 50,000-year-old Neanderthal bones, unearthed at Chagyrskaya cave in Russia.

Previously, researchers suggested that infectious diseases could have contributed to the Neanderthals' demise based on signs in viral and bacterial genomes of when those pathogens first infected humans – long enough ago that humans could have carried pathogens from Africa and passed them on to Neanderthals in Europe.

Otherwise, researchers have used mathematical models to simulate the spread of diseases between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals (H. neanderthalensis), and their differing immunity.

But with ancient DNA so difficult to sample and sequence, fragmented by all the thousands of years it has weathered, more direct evidence that Neanderthals were infected by pathogens that cause common illnesses today, but could have killed our kin, has been lacking.

"To support [this] provocative and interesting hypothesis, it would be necessary to prove that at least the genomes of these viruses can be found in Neanderthal remains," molecular biologist and senior author of the new study, Marcelo Briones, told New Scientist's James Woodford. "That is what we did."

Briones, along with evolutionary geneticist Renata Ferreira of the Federal University of São Paulo in Brazil and colleagues, sampled DNA from the skeletons of two male Neanderthals.

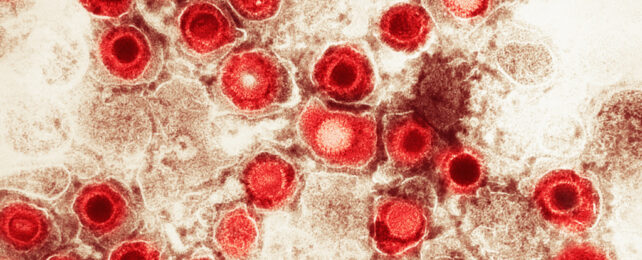

There, amongst the Neanderthal genome, they found snippets of DNA that resembled three modern viruses: adenovirus, which today causes common colds; herpesvirus, the culprit behind cold sores; and papillomavirus, transmitted during sex and causing genital warts.

In modern humans, these viruses can cause persistent or even lifelong infections where the virus evades the immune system and lies dormant for years or decades. So it's possible they also clung to Neanderthals, although how those infections manifested, as mild maladies or something more severe, is not yet known.

The study shows that it's feasible to find and extract remnants of viral DNA in the remains of ancient hominins. The oldest viral DNA found before this was a 31,000-year-old herpesvirus detected in H. sapiens teeth excavated from Siberia.

But the team stresses their findings are preliminary, saying the fragments indicate only the "possible presence" of viral DNA remnants in Neanderthal remains. Their study also hasn't been peer-reviewed.

Let's not forget either that there have been a host of other theories put forward about what wiped out Neanderthals. Neanderthals might have struggled to adapt to some sudden environmental change, or humans could have outcompeted Neanderthals for food and other resources.

However, those theories started falling out of favor more than a decade ago when researchers began to realize Neandertals were skilled hunters, fire wielders and social beings too.

Other suggestions popular among paleoanthropologists include the already small Neanderthal populations simply petering out, or that humans lived in larger groups, giving our ancestors a greater diversity of genes and ideas to work with.

"It is likely that a combination of these factors, along with other unknown factors, contributed to the eventual disappearance of Neanderthals," Ferreira and colleagues acknowledge.

The research has been posted to the bioRxiv preprint server ahead of peer review.