In the bowels of a Laotian cave, illuminated by faint sunlight and bright lamps, scientists have unearthed the earliest known evidence of our human ancestors making their way through mainland Southeast Asia en route to Australia some 86,000 years ago.

Any trace of human remains is a delight for archaeologists – but none more so when they dust off a discovery, date it, and realize it could push back timelines of early human migration in an area by more than ten thousand years.

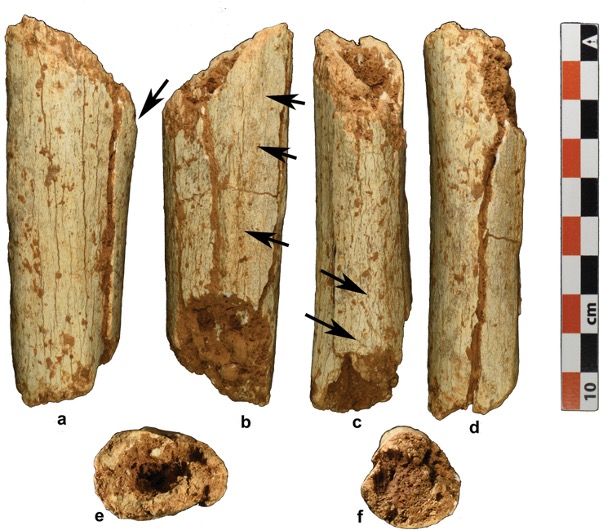

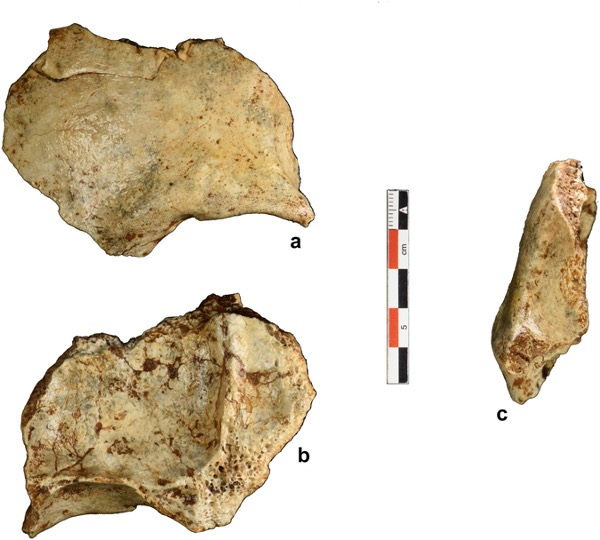

The international team of researchers behind this new discovery dug deeper than others had gone before in a karst cave in northern Laos, unearthing a skull fragment with delicate features, and the shard of a leg bone.

They estimate the two human fossils are between 86,000 and 68,000 years old, by using five different dating techniques to reconstruct the timeline of the cave site in which early humans sheltered on their journeys southward.

Tam Pà Ling Cave, where the bones were found, has a deep history of human occupation, though it is a contested one. A handful of human fossils including two jawbones previously found in shallower layers of sediments – shipped to the United States for study before being returned home to Laos – have dated to between 70,000 and 46,000 years old.

However, researchers cannot date the fossils directly, as the site is a World Heritage area and the fossils are protected by Laotian law. They also can't rely on their usual dating techniques because the sediments contain charcoal that washed into the cave and wasn't burnt there.

For this new study, the team led by biological anthropologist Sarah Freidline of the University of Central Florida, turned to luminescence dating and other techniques to get an age estimate of the sediments surrounding the newly discovered fossils, the deepest of which was found at nearly 7 meters (23 feet).

Their results bolster age estimates for the fossils found previously at Tam Pà Ling Cave, and extend the chronology of the site by some 10,000 years.

What's more, the cave is more than 300 kilometers (186 miles) from the sea so the discovery suggests our migratory ancestors didn't just follow coastlines and islands on their journeys out of Africa, but traversed forested regions and river valleys, the natural corridors of a continent.

"Without luminescence dating this vital evidence would still have no timeline and the site would be overlooked in the accepted path of dispersal through the region," says geochronologist Kira Westaway of Macquarie University in Australia.

"Tam Pà Ling plays a key role in the story of modern human migration through Asia but its significance and value is only just being recognized," adds University of Copenhagen palaeoanthropologist Fabrice Demeter, senior author of the study.

Sifting through sediments that hadn't seen the light of day for millennia and carefully discerning their layers under a microscope, the team found those sediments slowly piled up over some 86,000 years – and have encased a record of human presence at the cave spanning roughly 56,000 years.

As for the two new human fossils, the researchers dated two bovid teeth found in close proximity, to refine their age estimates. The fractured skull bone is 73,000 to 65,000 years old, the team found, and the tibia dates to 77,000 years old.

According to current genetic evidence, however, these early human migrants contributed hardly any genetic material to modern-day populations.

Instead, the skull bone "joins the other hotly debated fossils from southern and central China that suggest an earlier, possibly failed, dispersal" from Africa into Southeast Asia, Freidline and colleagues write.

In their paper, the team notes how the skull fragment was "remarkably gracile", its delicate features resembling those of more recent Homo sapiens remains found in Japan and Laos' closest neighbor, Vietnam.

They say this suggests whomever the skull belonged to descended from an immigrant population moving through the area, rather than from archaic hominins such as Denisovans who were also in the region and exhibited more robust features.

It could well be that early human explorers set out in waves, traversing Southeast Asia until they navigated across seas, onto Australia and throughout its deserted interior. Along the way, some groups petered out where others later succeeded – eventually giving rise to the oldest continuing culture on Earth.

"This really is the decisive paper for the Tam Pà Ling evidence," says Westaway, one of the study authors.

"Finally we have enough dating evidence to confidently say when Homo sapiens first arrived in this area, how long they were there and what route they may have taken."

The study has been published in Nature Communications.