Archaeologists have revealed what could be the oldest stone tools ever found, and they think someone other than our closest Homo ancestors may have made them.

Unearthed in 2016 at Nyayanga, Kenya, on the banks of Lake Victoria, the ancient implements fit with the design of the Oldowan toolkit, the name given to the earliest kinds of stone tools made by human-like hands.

According to dating estimates, the newly discovered tools were made between 2.6 and 3 million years ago, before being buried for eons in silt and sand. In total, 330 artifacts were found among 1,776 fossilized animal bones that showed signs of butchery.

Before this, the oldest known Oldowan tools dated to 2.6 million years ago.

While the age of the newfound tools may be further refined, their creation coincides with a time when ancestors of Homo sapiens roamed alongside other early humans, signaling a huge technological milestone for their creators – whomever they might have been.

"With these tools you can crush better than an elephant's molar can and cut better than a lion's canine can," says Rick Potts, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian Institute's National Museum of Natural History, who was part of the study.

"Oldowan technology was like suddenly evolving a brand-new set of teeth outside your body, and it opened up a new variety of foods on the African savannah to our ancestors."

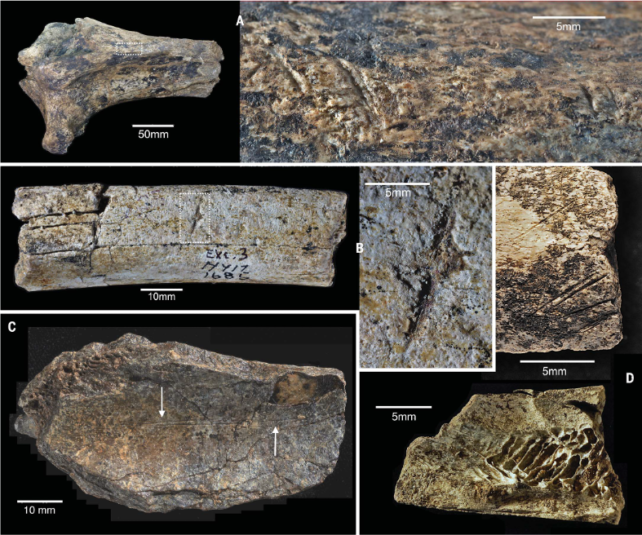

Hammerstones and sharp-edged flakes struck from stone cores were excavated along with fragments of rib, shin, and scapular bones from hoofed ruminant mammals called bovids (such as antelope) and hippopotamids.

As you can see in the images below, the bones bear deep cut marks where the tool makers sliced flesh from bone. The evidence suggests they even crushed some bones to extract bone marrow, and used the tools to pound plant material.

So effective were these tools that the technology would spread across Africa over the millennia. More recent Oldowan sites dated to 2 million years old have been found from northern to southern Africa, in both grassy and wooded habitats.

But until now, the earliest Oldowan sites were confined to Ethiopia's Afar Triangle, in two localities roughly 50 kilometers (31 miles) apart.

The Nyayanga site expands the known geographic range of the earliest Oldowan tools by more than 1,300 kilometers to the southwest. It also pushes their emergence back to roughly 2.9 million years ago, a result the researchers produced after narrowing their age estimates using a combination of dating techniques.

"What's really interesting is that here at this site you have some of the earliest evidence of butchery of megafauna, even before the advent of the use of fire," says Julien Louys from Griffith University's Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution.

That's not all. Along with the bones and tools, the team, led by anthropologist Thomas Plummer at City University of New York, found two teeth – an upper and lower left molar, one fractured in half, the other nearly complete – which the researchers identified as Paranthropus, a distant cousin of humans.

Carbon isotope analysis of the molar tooth enamel suggested the early humans from which they came ate a lot of plant foods, as well as devouring meat scavenged from animal carcasses.

One of the teeth was found in close association with the Oldowan artifacts, leading the researchers to suggest that perhaps these hominins made or were at least using the stone tools, not our more direct ancestors from the Homo genus.

Oldowan tools are often attributed to the genus Homo, but the overlapping existence of other hominins such as Paranthropus and now these two teeth suggest that Homo weren't the only ones to master making tools that helped them expand their diets.

Of course, the true makers of these tools will never be known, with any claims on their creators' identity likely to come under much scrutiny by other scientists or with new finds.

"The assumption among researchers has long been that only the genus Homo, to which humans belong, was capable of making stone tools," says Potts. "But finding Paranthropus alongside these stone tools opens up a fascinating whodunnit."

The research has been published in Science.