Humans are expected to die in record numbers as extreme heatwaves bake the world, and it is not just the very young and very old we need to worry about.

A new study in Mexico has found that since 1998, most heat-related deaths have occurred in those aged 18 to 34 – the group that one might expect to be most physically capable of withstanding extreme humidity and heat.

This climate-driven inequality disagrees with the previous literature, which suggests that elderly people are more likely to die from cold and hot weather.

But even though physiologically speaking, older people are more at risk from heatwaves, the new findings suggest younger people are ultimately more exposed.

"It's a surprise," says environmental and labor economist Jeffrey Shrader of the Center for Environmental Economics and Policy, an affiliate of Columbia University's Climate School.

"These are physiologically the most robust people in the population. I would love to know why this is so."

Shrader and his colleagues hail from a variety of US institutions, including Stanford University, Boston University, and Montana State University. They looked at Mexico because the nation has high-quality data on heat-related deaths and some of the most extreme humid heat exposures.

Between 1998 and 2019, there were about 3,300 heat-related deaths catalogued each year. Nearly a third of the deaths occurred in those aged 18 to 34.

The study could not say why, but researchers suspect that young people in Mexico are dying from heat-related deaths more than older folk because of a variety of behavioral, social, and economic factors.

Younger individuals, for example, are more likely to participate in outdoor activities, and they are also more likely to work in outdoor occupations with little flexibility for extreme weather events.

Previous studies of death certificates in Mexico have shown that extreme weather-related deaths are most common in men of working age.

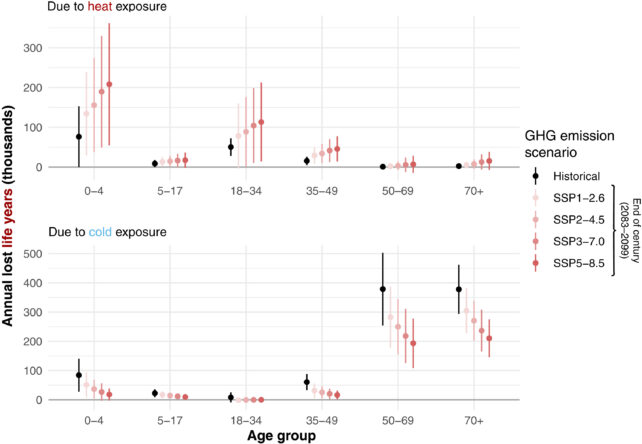

When considering the years of life lost to a premature, heat-related death, the researchers found there is an "outsized impact" on younger age groups in Mexico. Those under 35, for instance, account for 87 percent of life years lost because of heat exposure.

"Our finding that young people in Mexico are especially vulnerable to heat may have global implications," the authors explain.

"Hotter and lower-income countries – which are expected to be the most adversely affected by climate change – have among the youngest populations in the world currently and over the coming century."

People over 50 are often said to be most at risk from high humidity and heat, because older bodies are not as capable of cooling themselves off. But this new study suggests cold weather is a bigger threat to older bodies, and in the future, colder days are going to become more infrequent.

By 2100, deaths related to cold weather in Mexico are expected to drop by roughly a third in people who have at least reached middle age, and this decline is especially apparent in those over the age of 50, who are most vulnerable to freezing temperatures.

Younger folk probably won't be so lucky in the future. In a high emissions climate change scenario, researchers predict heat-related deaths in those under the age of 35 could increase by 32 percent in Mexico by 2100.

Those under the age of five will be the most affected, as very young children have a less developed thermoregulatory system.

If a kid under five experiences one day with an average wet-bulb temperature of 27 °C (81 °F) in Mexico, recent data suggests their risk of mortality increases by 45 percent compared to an average wet-bulb temperature of 13 °C.

But even adults, who are more robust to heat, can face serious physical risks from hot and humid weather if exposed for long enough.

Researchers are now investigating if young people elsewhere in the world are similarly impacted by heatwaves. That way, policymakers can take steps to protect the most vulnerable among us.

The study was published in Science Advances.