Psilocybin, the active psychedelic compound in magic mushrooms, has some curious effects on the human brain. There's the obvious, of course - hallucinations - but of increasing interest to scientists is its potential effectiveness as an antidepressant.

A recent trial showed that psilocybin was just as effective at managing depression as the most commonly prescribed type of antidepressant drug, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). There have been hints that psychedelics can induce neural adaptations, yet what psilocybin actually does to the brain and how long the effects last isn't exactly clear.

Researchers have now investigated this in mice, and found that the compound triggered an immediate, long-lasting increase in neuronal connections after just a single dose. It's a finding that could help explain psilocybin's antidepressant effects, according to the team.

"We not only saw a 10 percent increase in the number of neuronal connections, but also they were on average about 10 percent larger, so the connections were stronger as well," said neuroscientist Alex Kwan of Yale University.

Depression is thought to often be linked to the neurotransmitter serotonin, a hormone that helps transmit signals between regions of the brain. The action of psilocybin (and other serotonergic psychedelics, such as ayahuasca and mescaline) is also strongly tied to serotonin. This has led scientists to explore their potential as antidepressants - and, fascinatingly, they appear to be quite effective.

Given that SSRIs often have unpleasant side-effects, psychedelics could open up new pathways for treating depression. But not until we understand exactly what these compounds do to the mammalian brain.

To this end, a team of researchers led by neuroscientist Ling-Xiao Shao of Yale University sought to observe the effects of psilocybin on mouse brains.

They divided a population of mice into three groups. One was dosed with nothing but saline, as a control group. A second, positive control group was dosed with the anesthetic ketamine, another drug found to have surprising antidepressant benefits.

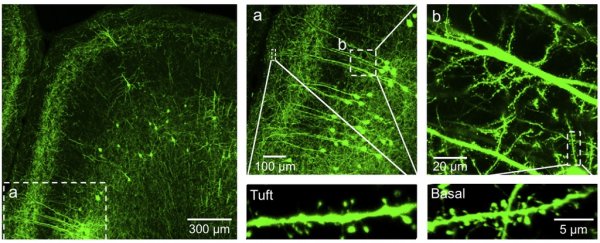

The final group was, obviously, dosed with psilocybin. The researchers then used a laser-scanning microscope to track brain changes in all three groups over several days, and then followed up after a month.

Compared to the controls, the psilocybin group had a pronounced increase in a type of neural structure called dendritic spines. These are small protrusions that can be found on the dendrites of the neuron, and they play a key role in the transmission of electrical signals in the brain and synaptic plasticity.

It's normal to have some turnover in dendritic spines, but conditions such as long-term stress and depression can see dendritic spine atrophy and a decrease in dendritic spine density.

The effect of psilocybin on the dendritic spines in mice was striking. Compared to the saline control group, an increase in dendritic spine density and size was detectable within just 24 hours of receiving one dose, and persisted over the next few days. Seven days after the dose, around half of the new spines were still there. At 34 days, around a third of the new spines persisted.

The distribution of the new dendritic spines was interesting, too. Some dendrites retained all the new spines they had grown, while others lost them completely. It's unclear what this means at this time, though.

To further investigate the result, the researchers dosed a second group of mice, then sacrificed them 24 hours later and dissected their brains to count the dendritic spines. This affirmed the ability of psilocybin to grow new spines in mouse brains.

Finally, when it comes to behavioral effects, the psilocybin group of mice seemed better able to cope with stress. When placed in a stressful situation - mild electrical shocks administered to the foot - the experimental group displayed greater inclination and ability to escape, and increased neurotransmitter activity, the researchers found.

The effect was similar to that of ketamine on dendritic spine density, which suggests that rapid neuronal structural remodeling might be key to drugs that have rapid antidepressant effects, such as ketamine and serotonergic psychedelics.

How compounds that act differently on the brain have the same effect, is unclear for now and warrants further investigation, the researchers said.

Nevertheless, the result is a promising one.

"It was a real surprise to see such enduring changes from just one dose of psilocybin," Kwan said. "These new connections may be the structural changes the brain uses to store new experiences."

The research has been published in Neuron.