A single serious knock to the skull could be all it takes to develop the nerve damage thought to be responsible for neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's disease, according to a recent study.

Most research into the neurological impact of head trauma has focussed on repeated damage, like that experienced by sports fighters or footballers; often, it's based on post-mortem results. So researchers from across Europe and the UK teamed up to look at the potential impact a single accident could have on the brain tissue of living volunteers.

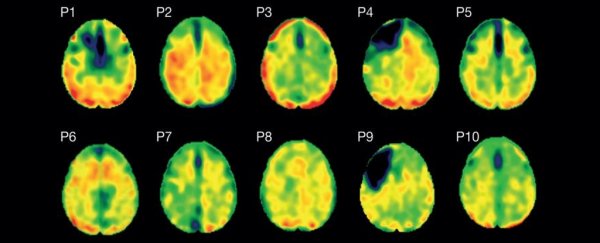

Using positron emission tomography (PET) scans, the researchers imaged the brains of 21 volunteers who'd experienced a moderate to severe head injury up to 37 years prior, due to a fall, assault, or road accident.

"Scientists increasingly realise that head injuries have a lasting legacy in the brain – and can continue to cause damage decades after the initial injury," says neurologist Nikos Gorgoraptis from Imperial College London.

A dozen of the volunteers qualified as disabled based on an evaluation, with the rest labelled as having 'recovered'. This traumatic brain injury group was then compared with 11 healthy individuals without any history of head trauma.

By administering a chemical that sticks exclusively to a repeating 'tangled' version of a protein called tau, the researchers were able to piece together individualised maps showing which brains had clumps of tangled tau and which didn't.

They noticed a significant increase in the amount of tau collecting in the right occipital lobe – the back part of the brain – among those who'd had a traumatic brain injury, regardless of whether they were disabled or had recovered.

"This is the first time we have seen these protein tangles in patients who have sustained a single head injury," says Gorgoraptis.

Tau proteins can be thought of as scaffolds that help stabilise cellular structures, particularly neurons.

In individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative conditions such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, these scaffolds appear rather kinked and knotted.

Along with the clumping of another protein called beta-amyloid, tangles of tau are thought to play a key role in the pathology of dementia-like diseases.

The exact mechanisms behind the interplay of these two misshapen proteins, and how they develop in the first place, is still a matter of ongoing study.

Research into treatments based on clearing beta-amyloid plaques and knotted tau proteins has also been rather hit-and-miss over the years, suggesting we still have much to learn on how they're involved in the steady degeneration of neural tissues.

The fact there appears to be some kind of relationship, though, makes them important markers for the progress of such debilitating conditions.

This particular study is an early stage investigation, based on a relatively small number of individuals, so we'll need more research for sure.It also doesn't mean a single head injury necessarily causes long lasting damage, let along dementia.

"It's well established that a major blow to head, for example from a road traffic incident or an assault, can increase your risk of developing dementia, but of course, this does not mean everyone with a head injury will get dementia," says James Pickett, Head of Research at Alzheimer's Society.

There was also no indication that this tangles themselves had any noticeable impact on the memory or behaviour of those affected.

But the researchers believe the most promising outcome of their research is the scanning method: combining PET with a chemical flag for tau clumps to keep a close eye on signs of trouble.

"What is exciting about this study is this is the first step towards a scan that can give a clear indication of how much tau is in the brain, and where it is located," says Gorgoraptis.

"As treatments develop over the coming years that might target tau tangles, these scans will help doctors select the patients who may benefit and monitor the effectiveness of these treatments."

Medical professionals are already calling for increased vigilance when it comes to activities that carry a risk of repeated blows to the head.

Knowing even just a single injury can leave traces of damage deep inside our brains makes it more important than ever that we develop the tools to better diagnose dementia as early as possible.

This research was published in Science Translational Medicine.