New research on one of the most fascinating Dead Sea Scrolls suggests there's something highly unusual about where and how it was made.

Estimated to be close to 2,000 years old, the remarkably well-preserved Dead Sea Scrolls contain ancient texts of great historical importance. Since the initial discovery in 1947 by Bedouin shepherds, scholars have reconstructed over 900 of these ancient Hebrew texts. While the majority are in tatters, a handful remain intact, even to this day.

The Temple Scroll is one of the largest and best-preserved of the bunch. It's also amongst the most special.

Found in a cave just north of the Dead Sea in 1956, the text was allegedly sold by a group of Bedouins to an antiquities dealer, who then wrapped it in cellophane and put it in a shoebox under a floorboard for safe-keeping. Eleven years later, when scholars at last got their hands on it, the precious manuscript was severely damaged by moisture.

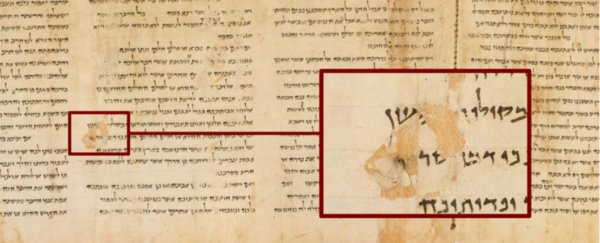

Today, the Temple Scroll is the thinnest of all the Dead Sea Scrolls discovered. At just one-tenth of a millimetre (roughly 250th of an inch), the writing material is razor thin, and yet this remarkable manuscript still unrolls for more than 8 metres, providing the clearest and whitest writing surface in the collection.

While ancient techniques for parchment-making differed in the East and the West, most were made from animal skin that had been cleaned and scoured of all hair and fat. This skin was then stretched and dried, and sometimes rubbed with salt, too. Eastern parchments were various shades of brown, while Western parchments were usually un-tanned.

The Temple Scroll doesn't fall into either of these categories. It is different from other scrolls in that its text appears on the 'flesh' side and not the 'hair' side. What's more, the ink on this particular parchment appears to sit on an inorganic layer, just above the surface.

Researchers wanted to figure out why, so taking a tiny fragment of the scroll - about 2.5 cm wide (1 inch) - they used a variety of non-invasive tools to map the parchment's chemical composition in high resolution.

"These methods allow us to maintain the materials of interest under more environmentally friendly conditions," explains James Weave, a scanning electron microscopist from Harvard University, "while we collect hundreds of thousands of different elemental and chemical spectra across the surface of the sample, mapping out its compositional variability in extreme detail."

What they found was completely unexpected: a previously unknown technique for making parchment in ancient times.

Spread in varying concentrations across the surface, the team identified an odd mix of sulphur, sodium, and calcium. These elements suggest a special coating - laced with various salts - was somehow applied to the parchment before any words were written.

"[T]his study has far-reaching implications beyond the Dead Sea Scrolls," says chemist Ira Rabin from Hamburg University in Germany.

"For example, it shows that at the dawn of parchment making in the Middle East, several techniques were in use, which is in stark contrast to the single technique used in the Middle Ages."

The researchers think the inorganic layer, previously identified in the Temple Scroll, must be part of a unique production technology that could explain why the scroll is so bright and resilient.

"The [Temple Scroll] can, therefore, be classified as a Western parchment that was modified through the addition of an inorganic layer as a writing surface," the authors conclude.

In many ways, however, the results raise more questions than answers. The composition of this special coating, the authors say, does not match water from the Dead Sea, which means it must have come from somewhere else. Where exactly, they're not sure.

"I am not the least surprised to learn that a part of the scrolls was not prepared in the Dead Sea region," bible scholar Jonathan Ben-Dov, who was not involved in this research, told The Guardian.

"It would be naive to assume that they were all prepared there."

But just because the salts come from elsewhere doesn't mean the Temple Scroll was necessarily produced somewhere else. After all, the special coating could have been brought in to the region from somewhere else.

More research will need to be done to locate the origin of this coating and to better understand how this technique might prolong a scroll's life for two thousand years or more.

The findings were published in Science Advances.