Physicists have uncovered an ultra-rare quasicrystal in a piece of Russian meteorite, and it's only the third time ever that we've seen one of these strange materials in nature.

Originating in outer space, these crystals aren't just incredible because of how rare they are - their atomic structure is so peculiar, for decades their existence was dismissed as "impossible", and they cost the scientist who first discovered them his job.

This new quasicrystal specimen was found by a team led by geologist Luca Bindi from the University of Florence in Italy.

They'd been examining a tiny grain of meteorite that landed in the Khatyrka region of the Russian far east five years ago, and identified piece of quasicrystal inside, just a few micrometres wide.

This is the third quasicrystal found in grains of this particular meteorite so far, which suggests that there might be more out there, and with even stranger structures.

"What is encouraging is that we have already found three different types of quasicrystals in the same meteorite, and this new one has a chemical composition that has never been seen for a quasicrystal," one of the team, Paul Steinhardt from Princeton University, told Becky Ferreira at Motherboard.

"That suggests there is more to be found, perhaps more quasicrystals that we did not know were possible before."

If you're wondering what the hell a quasicrystal is, they consist of an entirely unique atomic structure that basically combines the symmetrical properties of a crystal and the chaos of an amorphous solid.

Regular crystals, such as snowflakes, diamonds, and table salt, are made up of atoms that are arranged in near-perfect symmetry.

Polycrystals, including most metals, rocks, and ice, have more randomised and disordered structures, just like amorphous solids, such as glass, wax, and many plastics.

Back in 1982, Israeli chemist Daniel Shechtman proposed that another type of atomic structure could exist in nature - a strange, semi-ordered form of matter, with an atomic structure that displays no repeating patterns anywhere you look.

When he found some in a sample of synthetic material he created in the lab, he reportedly told himself, "Eyn chaya kao," which translates to "There can be no such creature," in Hebrew.

Shechtman was awarded the 2011 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery, but not before being literally laughed out of his lab and ridiculed by his peers for decades for daring to suggest something so preposterous as a semi-ordered structure.

The reason quasicrystals are so unlikely is because for almost two centuries, perfect symmetry in atomic structures was believed to follow a very strict set of rules.

Before the existence of quasicrystals was confirmed, scientists assumed that for a structure to grow with a repeating, symmetrical structure, it could exhibit one of four types of rotational symmetry: two-fold, three-fold, four-fold, or six-fold.

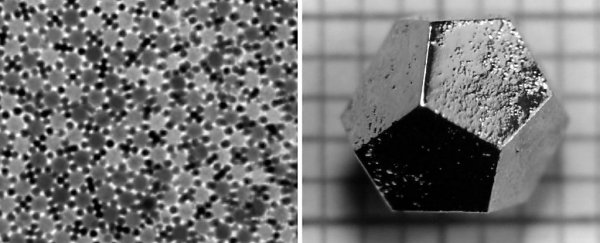

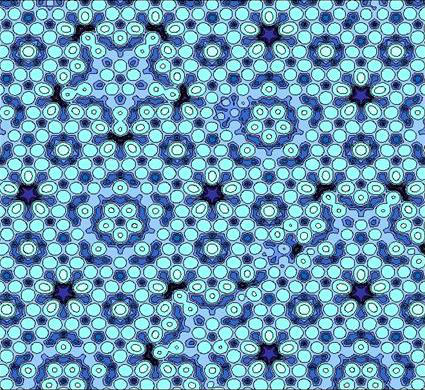

Quasicrystals broke this rule, because they have crystal-like structure with a five-fold rotational symmetry.

As Pat Theil, a senior scientist at the US Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory, explained to PBS, if you want to cover your bathroom floor in perfectly tessellating tiles, they can only be rectangles, triangles, squares or hexagons. Any other simple shape won't work, because it will leave a gap.

Quasicrystals are like pentagonal tiles - they can't tessellate like squares or triangles can, but other atomic shapes move in to fill in the gaps, like so:

J.W. Evans, Ames Laboratory, US Department of Energy

J.W. Evans, Ames Laboratory, US Department of Energy

You can also see an example of this in the image at the top of the page.

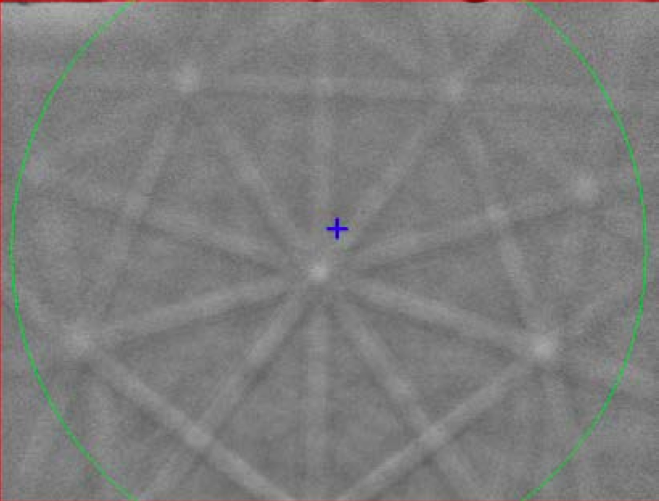

And here's an actual image of the newly discovered quasicrystal with five-fold symmetry:

Paul Steinhardt

Paul Steinhardt

While quasicrystals appear to be incredibly rare in nature - or on Earth, at least - they're actually really simple to make in the lab, and synthetic quasicrystals are now being built into everything from frying pans to LED lights.

When the researchers examined the composition of the new quasicrystal, they confirmed that it was made from a combination of aluminium, copper, and iron atoms, all arranged like the pentagon-based pattern on a soccer ball.

This is the first time this particular composition has ever been found in nature, suggesting that we're still only on the very cusp of understanding this bizarre form of matter.

The research has been described in Scientific Reports.

Top image credit: Quasicrystal atomic structure (L): Talapin et al; Synthetic quasicrystal (R): US Department of Energy