Male roundworms are worse at learning from experience than their mates, according to a new study, often to the point of embracing life-threatening risks.

Curiously, this lack of good judgment seems to settle down once they've had sex, suggesting an urge to reproduce dominates the male worm's brain over risk of harm.

The researchers link this phenomenon to a specific protein in the worms' brains – one that is closely related to a protein found in other animals.

In roundworms, the protein is called neuropeptide receptor, NPR-5, and it is involved in foraging and escape responses, seeming to regulate male learning by modifying brain activity.

This receptor has an equivalent in mammals, including humans. Ours is activated by a neuropeptide called NPY, and it is a key regulator of various behaviors, including learning and memory.

"In past studies, scientists discovered that female mice have lower levels of NPY than males, and they postulated that this is why they are more sensitive to stress in response to danger," explains Meital Oren-Suissa, who leads the Oren Lab in Weizmann's Department of Brain Sciences.

"Even though human behavior is far more complex, our study lays the groundwork for understanding the differences between the sexes in more complex organisms."

The study features Caenorhabditis elegans, a species widely used as a model organism. C. elegans has a no-frills nervous system with a few hundred nerve cells, and it's the only species whose neuronal connections have been fully mapped in both sexes. Those connections are all identical at birth, deviating by sex only once the worms mature.

The species is ideal for illuminating genetic differences between nematode sexes, since an individual worm's sex is primarily determined by genes, without complicating factors like hormones.

Unlike mammals, roundworms have two sexes: males and hermaphrodites, which can be considered 'self-fertile' females with the ability to create their own sperm and reproduce with themselves.

The study tested both sexes' ability to learn from experience. Using harmful bacteria that smell appealing to C. elegans, the authors first exposed each sex to a fragrant poison.

Once they had experience with this toxin, worms got to choose between the toxic bacteria or a less appetizing, but harmless option. Exposed hermaphrodites were quick to switch to the less harmful food, the study found, but most exposed males stuck with the better-smelling bacteria, even as it sickened them. Only after much more extended training periods did the males start to avoid the toxic food.

In exposed hermaphrodite worms, neurons linked to olfactory repulsion became more active when they encountered toxic food again, but a similar effect didn't occur in exposed males.

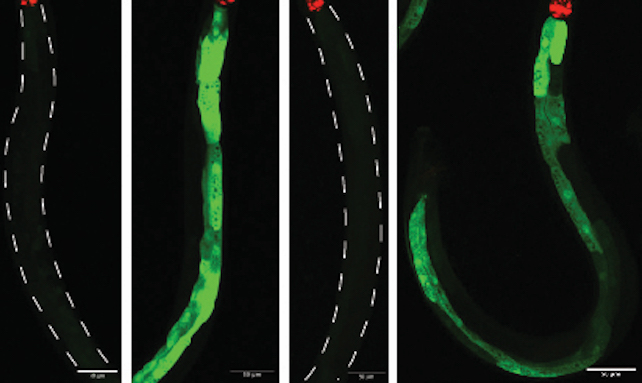

To investigate why that is, the researchers did some tinkering, genetic engineering hermaphroditic worms with male nervous systems. This 'brain swap' was enough to cause a clear decline in the worm's ability to learn.

Tellingly, making male worms associate illness with the smell of the toxic bacterium required something more than just tweaking their nervous system. A change in the gender of their digestive anatomy was required as well.

"This and other findings led us to postulate that the digestive and nervous systems communicate with one another – possibly using neuropeptides, short proteins that attach themselves to neurons and affect them – and that this communication represses the worms' ability to learn," says lead author and neurobiologist Sonu Peedikayil-Kurien, a doctoral student at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

When males were exposed to the toxic bacteria, researchers noticed reduced expression of the NPR-5 receptor in the brain. So they created males that completely lacked this receptor, enhancing their learning in the process.

That cognitive advantage vanished when researchers restored NPR-5 expression, leading the researchers to suspect this receptor suppresses learning in males.

And while learning to avoid danger is usually adaptive, males also face evolutionary pressure to prioritize reproduction, explains Oren-Suissa, who leads the Oren Lab in Weizmann's Department of Brain Sciences.

"One important point that we discovered in this context is that when we allowed male worms to mate with female worms during the [exposure] period, we saw that their ability to learn from experience improved," Oren-Suissa says.

"In fact, you could say that the receptor we identified is responsible for the fact that males will prioritize reproduction over learning from experience as part of their decision-making process," she adds.

"We know that male worms will abandon food to look for a mate, so it is possible that their urge to procreate overcomes other evolutionary pressures, such as the need to avoid danger."

The study was published in Nature Communications.