A pair of orcas terrorizing white sharks off the coast of South Africa may have captured the popular imagination, but their activities may be quite damaging, new research suggests.

Port and Starboard, as the orcas (Orcinus orca) are known, have been documented hunting white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) off the coast of South Africa for years, handily eviscerating them to feast on their nutritious livers, potentially reducing shark numbers in the area.

The impact of a declining shark presence has been difficult to determine, but we may be closer to an answer. Over the last few decades, white sharks have disappeared entirely from False Bay near the Cape of Good Hope – and the cascading effects of the loss of a top predator have been remarkable.

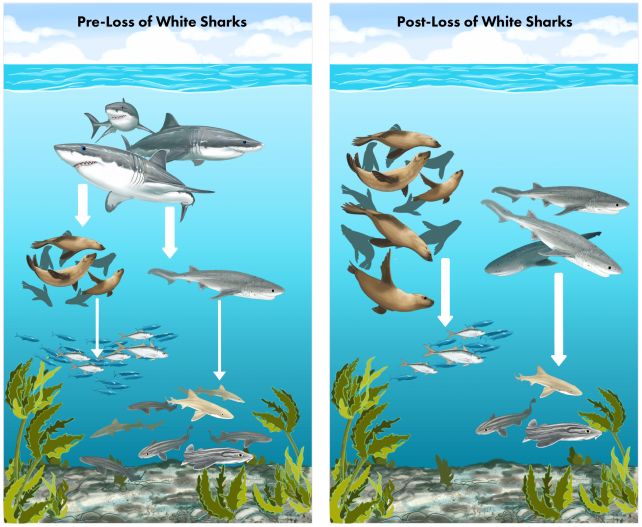

"The loss of this iconic apex predator has led to an increase in sightings of Cape fur seals and sevengill sharks, which in turn has coincided with a decline in the species that they rely on for food," says marine ecologist Neil Hammerschlag, formerly of the University of Miami.

"These changes align with long established ecological theories that predict the removal of a top predator leads to cascading effects on the marine food web."

An ecosystem is a delicate balance maintained by the interaction of the organisms that inhabit it. Although the predators at the top are considered scary by some, removing them from the environment has significant consequences.

Suppression of natural predators in Pando forest in Utah, for example, has allowed deer and elk to run riot, feasting on the ancient aspen colony and slowly killing it.

For more than 20 years, scientists have been monitoring wildlife populations in False Bay. This meant that they were able to see, in real time, the decline and ultimate disappearance of white sharks from the ecosystem there, and the consequent changes in populations of other species in the food web.

From 2000, scientists conducted standardized surveys of white shark sightings at Seal Island, and until around 2015, the shark population was pretty stable. After 2015, however, sightings started to fall dramatically; by 2018, there were no sharks to be seen.

The reason for this hasn't been officially confirmed. It's worth noting, however, that white sharks started washing up along the southern coast of South Africa, without their livers, in 2015 – attacks that would later be traced to Port and Starboard.

Although the cause of the shark disappearance is yet to be confirmed, we know the effects. White sharks prey on Cape fur seals (Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus). With no sharks around to keep their numbers in check, seal populations boomed.

At the same time, sevengill sharks (Notorynchus cepedianus) started appearing – large-bodied sharks that are both prey and competitor to white sharks.

As the numbers of Cape fur seals and sevengill sharks rose, populations of the species they prey upon in turn dramatically declined – small fish for the seals, and small sharks for the sevengills.

We know, based on other animal population booms, that a sudden increase in food competition between members of the same species can have dire consequences, with individuals taking greater risks to access food, and the weaker individuals starving when they are unable to compete.

It may take some time for the ecosystem to recover balance; and, once it does so, it could be very different from the ecosystem it was before.

Such changes are pretty normal in the natural world – after all, the world we live in today looks very different from the world of, say, 11,000 years ago, at the end of the last glacial period, or the world 70 million years ago, before the dinosaurs were eradicated.

However, understanding what drives such changes in the Anthropocene can help us try to minimize our own impact, and protect vulnerable habitats and the animals that need them to survive.

At least 17 sevengill #sharks have been killed by infamous #killerwhale pair Port & Starboard this week in South Africa. Only the livers were eaten with the leftover carcasses washing ashore [1/3] 📸 @MarineDynamics Christine Wessels pic.twitter.com/PQVk1KI9mF

— Dr. Alison Kock (@UrbanEdgeSharks) February 24, 2023

Port and Starboard have been observed hunting white sharks around Gansbaai and Mossel Bay, both further along the southern coast of South Africa.

The pair has also been sighted hunting in False Bay, although white sharks are not among the prey observed in that specific area. Nevertheless, it's reasonable to infer that their ongoing mischief at least plays a role in the changes at False Bay.

However, we cannot rule out overfishing, pollution, and shark cull programs as contributing factors, either. This is information that is relevant to understanding the wider impact of our own activities.

"Future work at this site would benefit from understanding if and how community structure and function may have been altered and the extent to which they will continue to change through time," the researchers write in their paper.

"While impacts of apex predator declines are difficult to detect in the wild, especially in marine environments, they are likely more widespread than recognized given the pace and extent of apex predator declines globally."

The research has been published in Frontiers in Marine Science.