For the millions of us plagued by hypersensitive, overactive, or downright abusive immune systems, it can feel like you're constantly fighting your own physical self.

From incessant allergies to life-threatening anaphylaxis and debilitating autoimmune disease, the system that's supposed to be protecting us can be problematic when it goes wrong. Now, we might be closer to fixing these issues in an entirely new way.

Using transgenic mice and cultures of cells taken from human tonsils, researchers have now found evidence of how our bodies might defend against the mistakes that result in conditions such as asthma, food allergies, and lupus. They found a protein called neuritin, produced by immune cells. It acts a bit like an inbuilt, boss-level antihistamine.

"There are over 80 autoimmune diseases, in many of them we find antibodies that bind to our own tissues and attack us instead of targeting pathogens - viruses and bacteria," explained immunologist Paula Gonzalez-Figueroa from the Australian National University (ANU).

"We found neuritin suppresses formation of rogue plasma cells which are the cells that produce harmful antibodies."

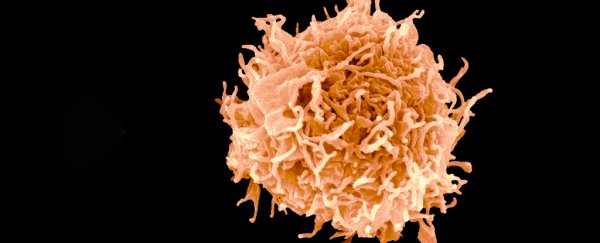

We have known for some time that the immune system's regulatory T cells suppress self-targeting antibodies and immunoglobulin E (IgE) - the antibodies that instigate release of the notorious histamines in response to allergies - but not how. It took Gonzalez-Figueroa and her team five years to work it out, with the help of genetically engineered mice and lab-grown human cells.

In another of biology's usual games of chain reactions, a special class of cells called follicular regulatory T (or Tfr) pumps out neuritin, which turns down production of IgE (this is its antihistamine action) and suppresses other processes that send plasma cells out on self-targeting missions (hence, quashing our autoimmune responses), the researchers found.

Mice without the ability to produce neuritin had an increased chance of dying from anaphylaxis when injected with albumin from an egg. These mice, genetically bred to lack neuritin-producing Tfr cells, grew a population of faulty plasma cells early on in their life. These are the cells that developed self-antigens.

But when the team treated Tfr-deficient mice by injecting neuritin into their veins, they had some striking results.

"Tfr-deficient mice treated with neuritin appeared healthy," Gonzalez-Figueroa and colleagues wrote in their paper, explaining the treatment led to the disappearance of the rogue B cell population too.

The team cautions they're yet to understand the full pathway involved in these immune mechanisms, or the effects of neuritin on other cellular processes. While neuritin has been studied in human nervous systems for quite some time, the exact way it triggers cells hasn't been clear.

To find out, white cells from human blood and tonsils were analysed in the presence of the protein, revealing clues on it acting internally. The results could lead to a better understanding of how we might use neuritin in the future to treat immune conditions.

"This could be more than a new drug - it could be a completely new approach to treat allergies and autoimmune diseases," Vinuesa said.

"If this approach was successful, we would not need to deplete important immune cells nor dampen the entire immune system; instead, we would only need to use the proteins our own body uses to ensure immune tolerance."

If they're right, and neuritin proves safe, it may one day allow the growing number of us facing allergies and autoimmune diseases some peace with our own bodies. Watch this space.

This paper was published in Cell.