When faced with a threat, hormones flood our bodies in preparation either for battle or a quick escape - what's commonly known as the 'fight-or-flight' response.

For decades, we've generally thought this response was driven by hormones such as adrenaline. But it now seems that one of the most important of these messengers could come from a rather unexpected place – our skeleton.

We usually think of chemicals like cortisol and adrenaline as the things that get the heart racing and muscles pumping. But the real star player could actually be osteocalcin, a calcium-binding protein produced by our bones.

As a response to acute stress, steroids of the glucocorticoid variety are released by the body's endocrine system, where they manage the production of a cascade of other 'get ready to rumble' chemicals throughout various tissues.

Researchers from the US, the UK, and India argue there's one tiny problem with this explanation of the fight-or-flight reaction. It isn't exactly fast.

While nobody is disputing that our bodies produce cortisol when stressed, the fact their main action is to trigger cells into transcribing specific genes – a process that takes time – makes it an unlikely candidate for a rapid physiological response.

"Although this certainly does not rule out that glucocorticoid hormones may be implicated in some capacity in the acute stress response, it suggests the possibility that other hormones, possibly peptide ones, could be involved," says geneticist Gerard Karsenty of Columbia University.

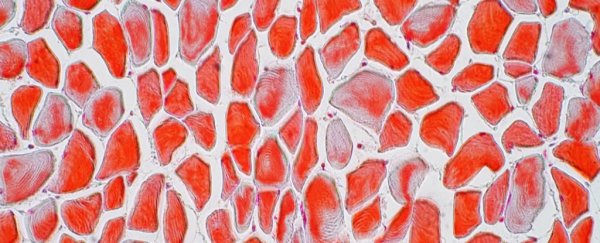

So Karsenty and colleagues went on the hunt for something a little more expedient, focussing on proteins released by bone cells that would potentially have a more immediate effect on animal metabolism.

Looking to the skeleton as a source might not be as weird as it first seems. After all, our bones evolved as a way to protect our squishy bits from being squashed, either by predator or accident.

"If you think of bone as something that evolved to protect the organism from danger – the skull protects the brain from trauma, the skeleton allows vertebrates to escape predators, and even the bones in the ear alert us to approaching danger – the hormonal functions of osteocalcin begin to make sense," says Karsenty.

Osteocalcin isn't in any way new to science, either. We've understood its function in bone development for nearly half a century, and in recent years begun to suspect it also has a hand in regulating our energy levels by affecting glucose metabolism.

It also seems to give an ageing memory a boost, at least in lab rodents. All useful things in moments of danger.

But it's still a surprising discovery that osteocalcin might also help to kickstart our acute stress response.

"It completely changes how we think about how acute stress responses occur," says Karsenty.

To test their suspicions, the researchers put lab mice under duress by restraining them for a 45 minute period. During that time, osteocalcin levels in the peripheral blood rose by half, while other skeletal hormones barely budged.

In another test, just 15 minutes after a few harmless (but uncomfortable) shocks to the feet, osteocalcin levels in the stressed mice jumped by a whole 150 percent.

Giving the test subjects a whiff of a chemical found in fox urine also elevated their peripheral osteocalcin levels. Importantly, these went up before their corticosterone levels began to climb, starting a few minutes after exposure and remaining high for another three hours.

Just to make sure it wasn't only a mouse thing, the team also checked the hormone in humans who volunteered to do a public speech and undergo a pulse-raising cross-examination. Sure enough, up the osteocalcin went.

In yet another series of tests, the team used rodents that were genetically engineered to lack the usual corticosteroid and other stress hormones, and found these animals continued to present a stress response.

In addition, a shot of osteocalcin in otherwise unstressed mice was all they needed to get twitchy, raising their heart rate, temperature, and levels of circulating glucose.

"Osteocalcin could explain past observations of an intact flight-or-flight response in humans and other animals lacking glucocorticoids and additional molecules produced by the adrenal glands," says Karsenty.

With the evidence building for the bone protein as such a strong motivator for dealing with stress, it stands to ask why we need hormones like cortisol at all. The researchers plan to unravel this mystery in future investigations.

This research was published in Cell Metabolism.