Nearly a million years ago, some devastating event nearly wiped out humanity's ancestors.

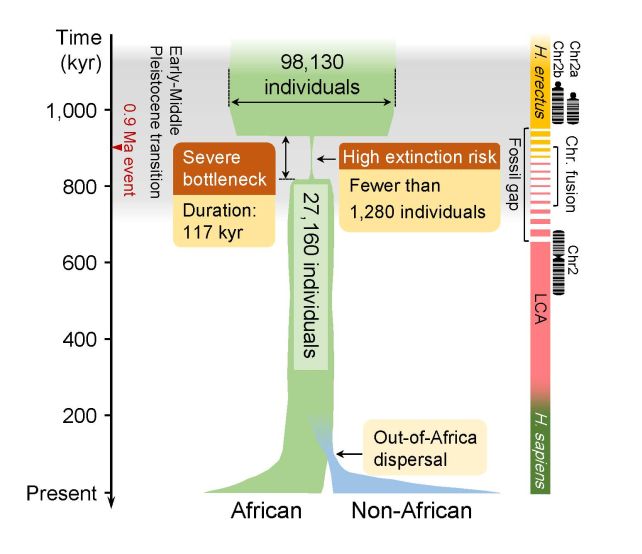

Genomic data from 3,154 modern humans suggests the population was reduced from approximately 100,000 to just 1,280 breeding individuals around 900,000 years ago. That's a jaw-dropping population decline of 98.7 percent that lasted 117,000 years and could have brought humanity to extinction.

The fact we're here today, and so numerous, is evidence that it wasn't. But the results, according to a team led by geneticists Haipeng Li of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Yi-Hsuan Pan of East China Normal University in China, would explain a curious gap in the human fossil record in the Pleistocene.

"The gap in the African and Eurasian fossil records can be explained by this bottleneck in the Early Stone Age as chronologically," says anthropologist Giorgio Manzi of Sapienza University of Rome in Italy. "It coincides with this proposed time period of significant loss of fossil evidence."

Population bottlenecks, as significant reductions in a group's numbers are known, are not uncommon. When a species is devastated by an event such as war, famine, or climate crisis, the resulting drop in genetic diversity can be traced through the progeny of the survivors. This is how we know that there was also a human population bottleneck in the Northern Hemisphere far more recently, some 7,000 years ago.

The further back in time you want to look, however, the more challenging it becomes to tease out a meaningful signal.

For this latest analysis, the research team developed a new method called the fast infinitesimal time coalescent process (FitCoal) to circumvent the accumulation of numerical errors usually associated with trying to unravel these past events.

They used FitCoal to analyze the genomic data of 3,154 people from around the world, from 10 African and 40 non-African populations, looking at how gene lineages have diverged over time. Their results showed a significant population bottleneck from around 930,000 to 813,000 years ago, which saw a current genetic diversity loss of up to 65.85 percent.

As to what caused the bottleneck, we won't ever be 100 percent sure what all the contributing factors might have been, but there was one major event taking place at the time that could have played a role – the Mid-Pleistocene Transition, during which Earth's glaciation cycles dramatically changed.

It's possible that climate turmoil could have produced conditions that were not kind to the human populations scrabbling for survival at the time, resulting in famine and conflict that reduced population numbers further.

"The novel finding opens a new field in human evolution because it evokes many questions," Pan says, "such as the places where these individuals lived, how they overcame the catastrophic climate changes, and whether natural selection during the bottleneck has accelerated the evolution of the human brain."

The bottleneck seems to have contributed to another interesting feature of the human genome: the fusion of two chromosomes to form chromosome 2.

Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes; all other hominids alive today – consisting of the great apes – have 24. The formation of chromosome 2 seems to have been a speciation event that encouraged humans on a different evolutionary path.

"These findings are just the start," Li says. "Future goals with this knowledge aim to paint a more complete picture of human evolution during this Early to Middle Pleistocene transition period, which will in turn continue to unravel the mystery that is early human ancestry and evolution."

The research has been published in Science.