We've long assumed our species evolved from a tidy, single stream of ancestors. But life on Earth is never quite so straightforward, especially not when it comes to the most socially complex species we know: humans.

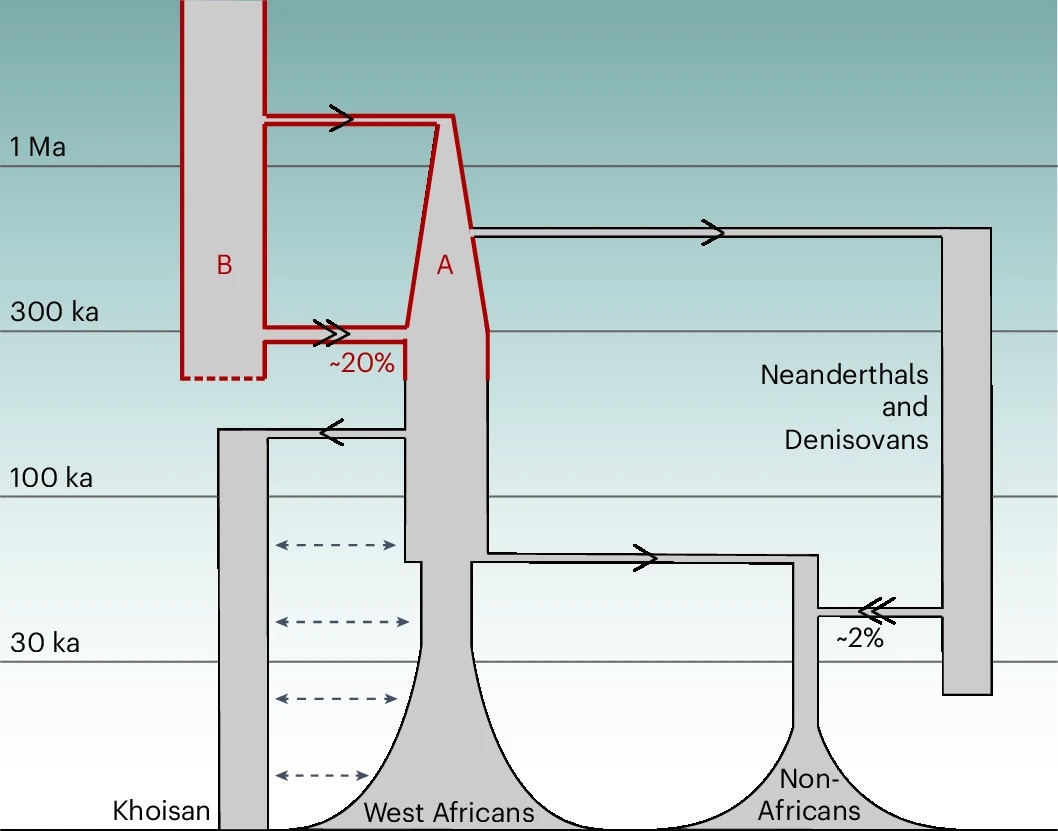

University of Cambridge researchers have now uncovered an estrangement in our family tree, which began with a population separation 1.5 million years ago and a reconciliation just 300,000 years ago.

What's more, according to their analysis of modern human DNA, one of these isolated populations left a stronger legacy in our genes than the other.

"The question of where we come from is one that has fascinated humans for centuries," says geneticist Trevor Cousins, first author of the published study.

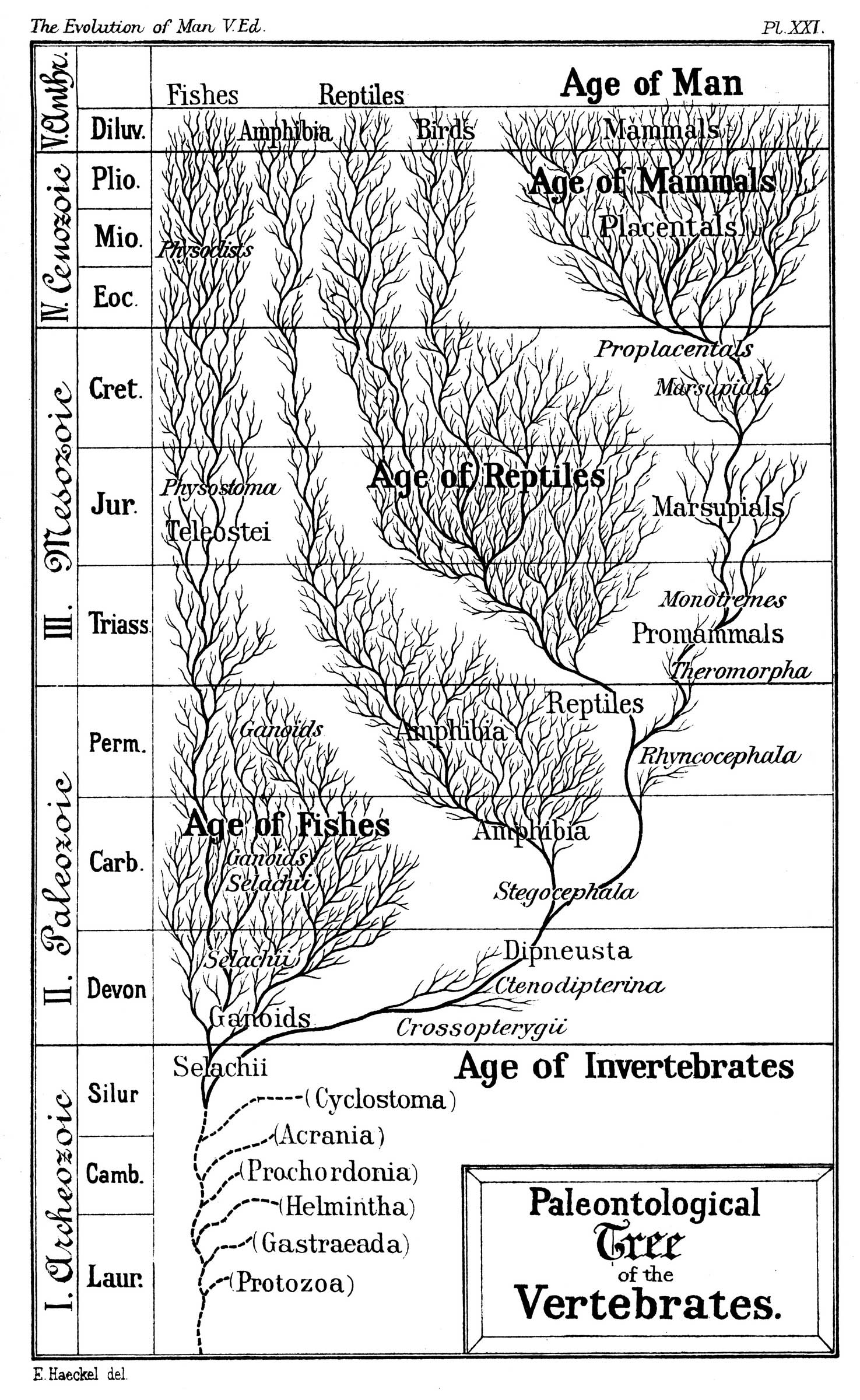

In biology, we often describe genetics and evolution with the metaphor of a branching tree. Each species' lineage begins with a 'trunk' at the base that represents a common ancestor, shared by all species at the crown.

As we trace the tree from base to tip, which represents evolutionary time, its trunk forks, again and again, each split representing an irreconcilable rift in populations that meant they could no longer breed with each other, and thus became separate species.

What an evolutionary tree does not capture is the on-again/off-again nature of intra-species dynamics, the many near-misses where one breeding group diverges into two, and then blends again back to one.

In some situations, this makes quite a mess of the neat and tidy tree diagram, and calls into question where the precise 'species' cutoff is.

"Interbreeding and genetic exchange have likely played a major role in the emergence of new species repeatedly across the animal kingdom," Cousins says.

Cousins and his co-authors, Cambridge geneticists Aylwyn Scally and Richard Durbin, had a hunch this kind of family drama would apply to our own species, Homo sapiens, which is technically more like a subspecies, except that there aren't any other groups left.

Aside from humanity's general penchant for love and war, there's some proof we 'spliced branches' with the Denisovans, and with a fair bit of Neanderthal DNA in our gene pool to this day, we know species lines must have blurred there, too.

The team used a statistical model based on the likelihood of certain genes originating in a common ancestor without selection events intruding. This was then applied to real human genetic data from the 1000 Genomes Project and the Human Genome Diversity Project.

A deep-rooted population structure emerged, suggesting modern humans, Homo sapiens, are the result of a population that split in two about 1.5 million years ago, and then, only 300,000 years ago, merged back into one. And it explains the data better than unstructured models, the norm for these kinds of studies.

"Immediately after the two ancestral populations split, we see a severe bottleneck in one of them – suggesting it shrank to a very small size before slowly growing over a period of one million years," says Scally.

"This population would later contribute about 80 percent of the genetic material of modern humans, and also seems to have been the ancestral population from which Neanderthals and Denisovans diverged."

It suggests the human lineage became irrevocably tangled much earlier than we thought. For instance, Neanderthal genes are only present in non-African modern human DNA, making up about 2 percent. The ancient mixing event 300,000 years ago resulted in only about 20 percent of modern human genes coming from the minority population.

"However, some of the genes from the population which contributed a minority of our genetic material, particularly those related to brain function and neural processing, may have played a crucial role in human evolution," Cousins says.

"What's becoming clear is that the idea of species evolving in clean, distinct lineages is too simplistic."

The research was published in Nature Genetics.