Mammals are born with all the oocytes (or egg cells) they'll ever need, but how the cells remain alive and active for so long is something of a mystery. A pair of studies have now revealed it could all come down to the robustness of their proteins.

The two investigations used traceable isotopes incorporated into growing mouse fetuses to measure the lifespans of proteins in their ovaries, finding many of them survived far longer than proteins in the rest of the body. The presence of these 'long life' molecules and the support they give oocytes and the surrounding cells seem to be crucial in maintaining fertility.

Put together by a team led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences in Germany, the first study analyzed oocytes in 8-week-old mice, when the animals were at their reproductive prime. Around 10 percent of the oocyte proteins produced while the animals were in utero were still present.

The researchers then looked at older mice to see how long it took for these persistent proteins to break down. The answer: not very quickly at all, relatively speaking. Some of the proteins remained in the ovaries of the mice for most of the animals' short lives.

"Our data establishes that many proteins in oocytes and the ovary are unusually stable, with half-lives well above those reported in other cell types and organs, including the liver, heart, cartilage, muscle and the brain," write the researchers in their published paper.

"The half-lives of many proteins are much higher in the ovary than in other organs, and many additional proteins are uniquely long-lived in the ovary."

A second study by a team led by US researchers also found evidence of long-lasting ovary proteins in young mice, including proteins that were present before the mice were born. Certain long-lasting proteins, such as ZP3, were identified for future studies.

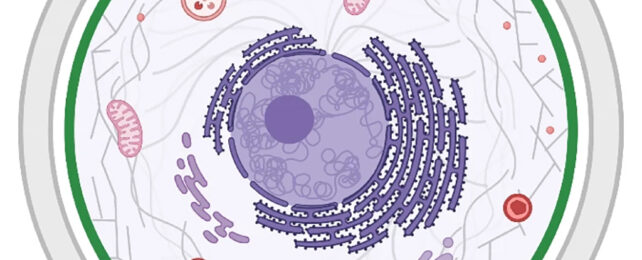

Some of these hardy proteins were present in the cell mitochondria, where a cell's energy is generated. Since mitochondria are inherited as part of the egg cell a mammal grows from, it could ensure these critical organelles can remain functional as they're passed from mother to offspring.

Eventually, even these proteins that live way beyond the norm fade away and die, the researchers report. That could be connected to the natural decline in a woman's ability to have children, the study suggests – and could ultimately point to ways to treat or at least better diagnose infertility.

The findings from these studies of mice still need to be replicated in humans, but if they are, it would represent a significant step forward in our understanding of fertility and how oocytes can be kept in a healthy state.

"The exceptional persistence of these long-lived molecules suggest a critical role in lifelong maintenance and age-dependent deterioration of reproductive tissues," write the researchers behind the second study in their published paper.

The research has been published in Nature Cell Biology and eLife.