The early Universe was a wild time. In the first 2 billion years following the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago, star formation positively roiled, and galaxies flared to life in the darkness, collided, and grew.

Interpreting the light that has traveled so far across space and time can be difficult, and we don't always get it right. In fact, the most powerful space telescope in operation has just revealed what might be a fascinating case of mistaken identity.

Discovered in 2013 as the source of rampant star formation just 880 million years after the Big Bang, a 'galaxy' named HFLS3 is not a galaxy at all. According to an analysis of data from the James Webb Space Telescope, HFLS3 is actually six galaxies undergoing an epic, giant collision at the dawn of time.

The study, led by astrophysicist Gareth Jones of the University of Oxford, has been accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics, and is available on preprint server arXiv.

HFLS3 boggled scientists when they found it in data from the Herschel space telescope. There it was, sitting at the very beginning of the Universe during the Epoch of Reionization, pumping out stars at an astounding rate of some 3,000 solar masses per year. The Milky Way, by comparison, produces up to around 8 solar masses of stars per year, even though the two objects were thought to have around the same mass.

This was challenging to explain, because galaxies weren't thought to be able to grow so big so early in the Universe, or have such a high rate of star formation.

But the Herschel observations, and subsequent Hubble observations, suggested that there was more going on, with hints that maybe there was more than one galaxy inside that distant glow.

Optimized for peering into the deepest reaches of space-time with the highest resolution yet, JWST allowed astronomers to take a more detailed look at HFLS3 than we had been able to obtain previously.

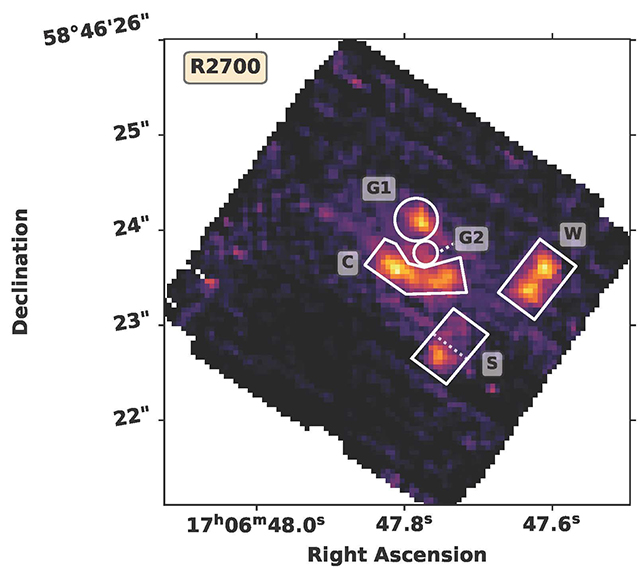

In September 2022, JWST's near-infrared NIRSpec instrument took observations of the swatch of sky in which HFLS3 can be found, and Jones and his team fell on the data with gusto. And, once they processed the data and teased apart the way the light had warped as it traveled across the Universe, they realized there were signs of six distinct galaxies within.

In a volume of space just 36,000 light-years in diameter, they found, HFLS3 consists of three pairs of small galaxies locked in a dance bringing them towards an inevitable collision. That collision would have taken place within a billion years of the observation; that's a pretty short space of time for something as epic as a galactic collision.

They're so close to each other that their gravitational interactions are churning up their star-forming material, causing it to ignite with star formation, thus also explaining the extremely high rate at which new stars are being born. And the discovery offers a fascinating snapshot into the way galaxies interacted and grew during the period known as the Cosmic Dawn.

It warrants, the researchers say, further and closer investigation, both of this and other sources.

"Taken together, our results require a drastic reinterpretation of the HFLS3 field," they write in their paper.

"HFLS3 is likely not an extreme starburst, but instead represents one of the densest groups of interacting star-forming galaxies within the first billion years of the Universe. Recent and ongoing high-resolution observations … will help to further characterize this unique field."

The research has been accepted into Astronomy & Astrophysics, and is available on arXiv.