Sold under the brand names Ozempic and Wegovy, the diabetes-treatment drug semaglutide is also proving incredibly effective in the management of weight loss.

Health problems attributed to obesity might also be expected to ease following treatment, though evidence of the drug's effectiveness on conditions such as knee pain is limited.

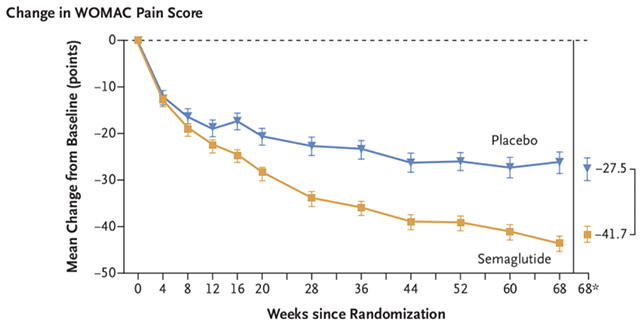

In a phase 3 clinical trial involving 407 participants, an international team of researchers found that a weekly dose of 2.4 milligrams of semaglutide significantly beat placebo treatments for reducing weight and relieving symptoms of obesity-related osteoarthritis over a 68 week period, improving the ability to complete physical activities like walking.

For some, the pain reduction was so drastic that they were effectively "treated out of the study", as rheumatologist Henning Bliddal from Copenhagen University Hospital in Denmark told Traci Watson at Nature.

The arthritic condition is brought on when the protective cartilage in the knee joints gets worn away, causing pain and stiffness that can be quite severe. Obesity is a major risk factor for knee osteoarthritis, and losing weight can help reduce the pain – two good reasons why the researchers wanted to investigate the potential benefits of semaglutide.

Semaglutide is what's known as a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA), which mimics the GLP-1 hormone that gets produced when we eat, tricking the brain into thinking we're full.

The drug has been proven effective for helping individuals lose weight, which in principle might ease the load on sore knees and even assist in the tissue's recovery. But preclinical studies also suggest GLP-1RAs may also work as an anti-inflammatory, potentially calming immune responses that trigger swelling and tissue damage.

On average, body weight dropped 13.7 percent in the group given semaglutide compared to 3.2 percent given placebos, while the reported pain scores dropped 41.7 points and 27.5 points respectively (the pain scale used runs from 0 to 96).

There are a few caveats to consider. The study was partly funded by Novo Nordisk, which manufactures semaglutide. Also, while participants were given advice about diet and physical activity routines during the trial, there were no checks on how much of this advice was followed.

It's also worth bearing in mind that semaglutide in its various forms is an expensive drug, and that weight can quickly pile back on when doses are stopped. Getting people to take the drug long term could be challenging.

Despite those issues, the study results offer plenty of early promise for a future treatment for knee osteoarthritis and the debilitation that goes along with it. There are treatments currently available, but they often come with limitations or side effects.

Those with the condition are often caught in a bind: knowing that physical activity and exercise can help them lose weight and improve their symptoms, but also being in too much pain to actually do anything about it. It's a ray of hope for the hundreds of millions of people living with knee osteoarthritis.

"Weight reduction along with physical activity is often a recommended approach to managing painful symptoms, but adherence can be challenging," says Biddal.

The research has been published in the New England Journal of Medicine.