A new study has added evidence to the hypothesis that our planet experienced a lull in geology between 2.2 and 2.3 billion years ago, when not a lot went on as far as rock-forming processes go.

The relatively dormant phase in our planet's history signals a significant change in tectonics, one that is fuelling discussion on exactly how continents form and could possibly provide better details on exactly where we can find new deposits of various mineral resources.

The era known as the Palaeoproterozoic covers a rather exciting time in Earth's history, starting 2.5 billion years ago and ending around a billion years later.

Life was literally a lot simpler then. Days were four hours shorter. Our atmosphere was yet to have a lot of oxygen. There were the first global glaciation events. And the planet's first supercontinent – a huge chunk of land called Columbia, or Nuna – was in the process of being formed.

As you might imagine, geologists are keen to understand how this far younger Earth behaved compared to today's more mature globe.

It seems as if around 2.45 billion years ago, there was something of a quiet spell beneath the surface, one that lasted around 250 million years.

Not that everybody is convinced – other interpretations of the research suggest it was business as usual throughout the Palaeoproterozoic.

With the jury still out, more evidence is needed. Which is just what a new study led by researchers from Curtin University has provided.

A close look at the existing data as well as new rock samples collected from Western Australia, China, Northern Canada and Southern Africa has added weight to what's described as a tectono-magmatic shutdown.

"Our research shows a bona fide gap in the Palaeoproterozoic geologic record, with not only a slowing down of the number of volcanoes erupting during this time, but also a slow-down in sedimentation and a noticeable lull in tectonic plate movement," says Curtin University geoscientist Christopher Spencer.

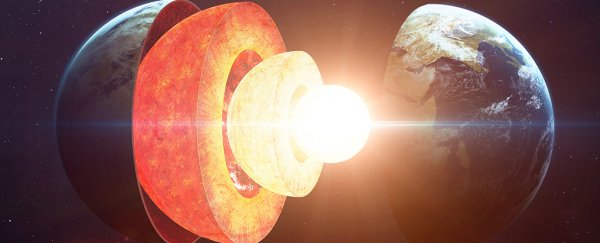

Earth's guts were a lot hotter a few billion years ago. For a while all that churning resulted in a whole lot of volcanic activity.

Whether that directly led to significant cooling, or if something else happened beneath the crust, nobody is sure.

But we can now be fairly confident that about 2.3 billion years ago, things went quiet under the lid. Volcanoes were temporarily out of fashion. Plate movements were subdued.

Earth was taking a break.

"This 'dormant' period lasted around 100 million years and signalled what we believe was a shift from 'ancient-style' tectonics to 'modern-style' tectonics more akin to those operating in the present day," says Spencer.

"It's almost as if the Earth experienced a mid-life crisis."

After a bit of a breather, things ramped up again. Chunks of ancient crust fractured into smaller pieces called cratons, which can today be found deep inside continental plates.

"Following this dormant period Earth's geology started to 'wake-up' again around 2.2 to 2.0 billion years ago with a 'flare-up' of volcanic activity and a shift in the composition of the continental crust," says Spencer.

Why did the mantle 'flare up' again after a quiet spell? The researchers aren't sure, but have speculated it might simply come down to a surge of accumulated heat.

Understanding the geological processes that led from 'supercratons' to the first supercontinent could help us understand how many of the mineral resources we rely upon formed and distributed.

More data is needed to fill in missing details on this geological 'mid-life crisis' model, but we can at least be grateful Earth didn't quit its job and run off with some young moon.

This research was published in Nature Geoscience.