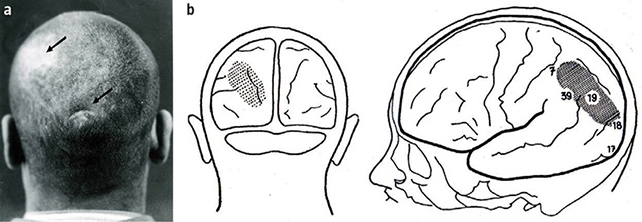

A newly published study has rediscovered one of the most singular and strange cases of brain injury in history: the case of Patient M, who, having been shot in the head in 1938 during the Spanish Civil War, woke up seeing the world backwards.

People and objects appeared to Patient M to be coming from the opposite side to where they actually were, something that extended to his hearing and sense of touch too.

He could read letters and numbers printed both normally and back-to-front, without his brain being able to see any difference between the two.

The world could also appear upside-down to Patient M, as well as backwards: he would be confused by men working upside-down on scaffolding for example.

Patient M was also able to read the time on a wristwatch from any angle.

It's a truly bizarre set of symptoms, but there were others too. They included seeing colors unstuck from their objects, objects appearing in triplicate, and color-blindness.

However, it's reported that Patient M dealt with all of this quite calmly.

Patient M was studied for nearly 50 years by Spanish neuroscientist Justo Gonzalo, and his analysis led to a significant shift in how we see the brain – by no means the only time that a freak injury has helped scientists to better understand the brain.

During the 1940s, Gonzalo proposed that the brain was not a collection of distinct sections, but instead has its various functions distributed in gradients across the organ – an idea that went against the conventional wisdom of the time.

"The brain was seen like little boxes," neuropsychologist Alberto García Molina, from the Institut Guttmann in Spain, told El País.

"When you altered a box, supposedly there was a concrete deficit. For Dr. Gonzalo, the modular theories couldn't explain the questions that emerged with Patient M, so he began to create his theory of brain dynamics, breaking with the hegemonic vision about how the brain works."

In studying Patient M and others with brain injuries, Gonzalo proposed that the effects of brain damage depended on the size and position of the injury.

He also showed that these injuries don't destroy specific functions, but affect the balance of a variety of functions – as was the case with Patient M.

Gonzalo identified three syndromes: central (disruptions across multiple senses), paracentral (like central, but with effects that aren't evenly distributed), and marginal (affecting brain pathways for specific senses).

It was pioneering work based on an incredible case, but it's not as well known as it should be – and now Gonzalo's daughter, Isabel Gonzalo-Fonrodona, has worked with García Molina on the new paper, outlining the research involving Patient M.

As the study says, single case studies have taught us about brain function for hundred of years, providing a valuable alternative source of scientific evidence to the meta-analyses and large clinical trials of today.

That ideas about the brain similar to Gonzalo's remain prominent is evidence that he was onto something in his interpretation of Patient M's injuries and backwards vision.

The research has been published in Neurologia.