Scientists have identified a new phenomenon they describe as "interactive dreaming", where people experiencing deep sleep and lucid dreams are able to follow instructions, answer simple yes-or-no questions, and even solve basic mathematics problems.

As well as adding a whole new level of understanding to what happens to our brains when we're dreaming, the new study could eventually teach us how to train our dreams – to help us towards a particular goal, for example, or to treat a particular mental health problem.

There's plenty about the psychology of sleep that remains a mystery, including the rapid eye movement (REM) stage where dreams usually occur. Being able to get responses from sleepers in real time, rather than relying on reports afterwards, could be hugely useful.

"We found that individuals in REM sleep can interact with an experimenter and engage in real-time communication," says psychologist Ken Paller from Northwestern University. "We also showed that dreamers are capable of comprehending questions, engaging in working-memory operations, and producing answers.

"Most people might predict that this would not be possible – that people would either wake up when asked a question or fail to answer, and certainly not comprehend a question without misconstruing it."

The researchers worked with 36 individuals in experiments across four different laboratories. One volunteer had narcolepsy and frequently experienced lucid dreams, while the others varied in terms of their experience with lucid dreaming.

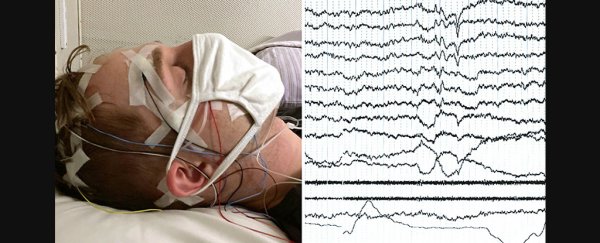

During the deepest stages of sleep, as monitored by electroencephalogram (EEG) instruments, scientists interacted with the study participants through spoken audio, flashing lights, and physical touch: the sleepers were asked to answer simple maths questions, to count light flashes or physical touches, and to respond to basic yes or no questions (like "can you speak Spanish?").

Answers were given through eye movements or facial muscle movements agreed in advance. Across 57 sleep sessions, at least one correct response to a query was observed in 47 percent of the sessions where lucid dreaming was confirmed by the participant.

Confirmation of the lucid dreaming states was done in a blinded fashion, with sleeper responses needing to be agreed upon by several witnesses.

A summary of the experiments. (Konkoly et al., Current Biology 2021)

A summary of the experiments. (Konkoly et al., Current Biology 2021)

"We put the results together because we felt that the combination of results from four different labs using different approaches most convincingly attests to the reality of this phenomenon of two-way communication," says neuroscientist Karen Konkoly from Northwestern University.

"In this way, we see that different means can be used to communicate."

The individuals involved in the study were usually woken up after a successful response in order to get them to report on their dreams. In some cases, the external inputs were remembered as being outside or overlaid on the dream; in others, they came through something inside the dream (like a radio).

In the published study the researchers compare trying to communicate with lucid dreamers to trying to get in touch with an astronaut in space, and it's the immediacy of the responses that make this new approach so exciting.

The research could be helpful in the future study of dreams, memory, and how important sleep is for fixing memories in place. It might also come in useful in the treatment of sleeping disorders, and further down the line might even give us a way to train what we see in our dreams.

"These repeated observations of interactive dreaming, documented by four independent laboratory groups, demonstrate that phenomenological and cognitive characteristics of dreaming can be interrogated in real time," write the researchers in their paper.

"This relatively unexplored communication channel can enable a variety of practical applications and a new strategy for the empirical exploration of dreams."

The research has been published in Current Biology.