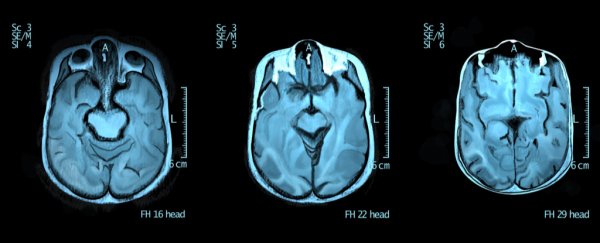

In spite of how they appear, the left and right hemispheres of the human brain tend to be far from perfect reflections of each other. Some neurological disorders can affect that imbalance, causing the two halves to appear strikingly alike.

So far, studies on whether autism is among those conditions have been less than convincing. To get a more definitive answer, researchers analysed thousands of brains and showed there is slightly more symmetry for those on the spectrum.

But what does that really mean?

To get this answer, scientists from the Enhancing Neuro-Imaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis consortium collected decades of brain scans from more than 1,700 individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder ( ASD) and more than 1,800 with no diagnosis.

The consortium were hardly strangers to analysing huge banks of data, having only recently conducted a similar study on ASD brain anatomy involving more than 3,000 subjects.

The condition covers a spectrum of characteristics that can make life a little more challenging for some, affecting their ability to socialise, communicate, and process stimuli.

With such variation in behaviours, sensations, and impact, tracing the traits making up ASD down to simple neurological differences is no easy task.

Doing so could help make the disorder easier to diagnose and lead to novel therapies, opening the way to providing better methods of assistance for those who need it.

So researchers have been busy looking for clues on all levels of anatomy, from the genes to the gross architecture of our squishy bits.

There have been plenty of investigations into the overall structures of autism-related brains, discovering subtle differences such as the thickness of the cerebral cortex and how key areas link together.

Comparing the ways our brain's mirrored hemispheres reflect each other is a fair way to understand how they develop and communicate.

After all, for most of us, it's differences both between and within the two halves that governs everything from movement to cognitive processes.

Unfortunately, there's still so much we don't know about this contrast between the hemispheres, or 'lateralisation'. So when it comes to learning how lateralisation might be linked with more profound neurological differences, we're still in the dark ages.

There are studies that have found people with ASD have unusually symmetrical brains. There are also studies that found no such thing.

They also tend to be more left handed, and seem less symmetrical in other areas of the brain.

If you're confused about what to make of the mess of conflicting studies, you're not the only one.

"Previous studies have suggested that people with autism spectrum disorder are less likely to have the typical asymmetries for language dominance or hand preference," says geneticist Merel Postema from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in the Netherlands.

"However, it has not been clear whether asymmetry of the brain's anatomy is affected in autism, because different studies have reported different findings."

Comparing the thickness of the cortex forming key parts of the brain's outer layer, the researchers found there was comparably less variability across the hemispheres in brains from people with ASD.

These differences didn't vary much depending on sex, medication, or IQ, making it more likely that there was something about autistic brains that accounted for this increased symmetry.

In spite of the significance of the results, it's not enough of a difference to base a diagnosis on.

"The very small average differences in brain asymmetry between affected people and controls mean that changes of brain asymmetry will not be useful in terms of clinical prediction", says the study's leader, Clyde Francks from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics.

"But the findings might inform our understanding of the neurobiology of autism spectrum disorder".

Some of the differences, for example, appeared in areas containing networks that work harder while we're resting. Just how this might account for some of autism's traits – if at all – is a task for future studies.

No doubt, there'll be more research on this in the future. Having more information on how our brain works as a whole not only helps us better understand how ASD arises, but how behaviours and functions common to all of us might develop.

This research was published in Nature Communications.