In the not-too-distant future, a planetary scientist will open up a tube of rocks that came from Mars.

Thanks to the Perseverance rover, there are at least 17 of these rock and regolith samples, just waiting for analysis on Earth. To get them, the rover has covered about 13 kilometers (8 miles) on its Mars geology field trip.

The rover has been drilling and scooping since shortly after landing, squirreling away rocks and sand into special tubes for transport.

It dropped its first load near a place called "Three Forks" this week. That tube contains bits of igneous rock it found in January of this year.

It wasn't just a "drop and run". Mission engineers had to make sure the tube landed safely. So, they did it slowly. First, Perseverance pulled the container out of its belly.

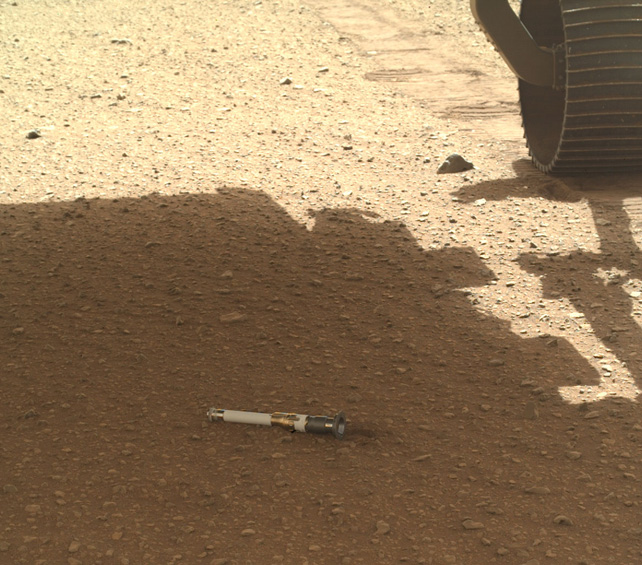

Then it looked everything over with a camera before dropping the tube down 90 centimeters onto the surface.

Then another image showed mission engineers the sample was safely in position on its side for easy pickup.

Eventually, all the containers Perseverance has filled will make their way to labs on Earth. Scientists will analyze them to understand the chemical and mineral properties of the samples.

From there, they can construct a more accurate geological and atmospheric history of the Red Planet.

"Choosing the first depot on Mars makes this exploration campaign very real and tangible," said David Parker, ESA's director of Human and Robotic Exploration. "Now we have a place to revisit with samples waiting for us there."

What will we learn from the Perseverance Mars rock samples?

Mars is an enigma of a planet. Its history is complex. Volcanoes exist there. How long ago were they active?

Canyons split the landscape. What caused those tectonic actions? Craters scar the planet, digging up material from deep beneath the surface. And, places on Mars clearly show evidence of flowing liquid water. Yet, no water flows there now. It's all locked up in subsurface ice or at the poles.

So, how do we find out more about the geological history of the planet?

The most direct way is to look at rock samples. Mars has igneous rock, as well as sandstones, mudstones, and clays. And, of course, there's dust and sand nearly everywhere. All of those can tell something about the time on Mars when lava flowed, lakes and oceans existed, and when it all happened.

Detailed technical analysis of igneous rocks will tell how long ago the volcanoes were active. Chemical and mineralogical clues in Mars rocks will help planetary scientists understand if they were in contact with water. Finally, all of that information should help scientists figure out if and when Mars could have supported life.

The rock samples that Perseverance gathers come from different rock "regimes" in Jezero Crater. Orbital images show that this region was once an ancient delta that was flooded with water. It appears to be rich in clay minerals and carbonates, which form only in the presence of water.

Those same carbonates contain a record of Mars's ancient climate. Yet, here's another interesting thing about them: on Earth, living organisms can also produce carbonates.

It's not clear if those on Mars have the same life-friendly origin, but it does make Jezero Crater a tantalizing place to sample.

Establishing a rock pipeline from Mars to Earth

The sample-gathering expedition using the tubes has been part of the program from the beginning. The original idea was to have the rover gather and deliver them to the NASA Sample Return Lander (SRL).

That mission is being planned and built by NASA and the European Space Agency for launch later this decade. It should land in Jezero Crater near Perseverance to make for easy delivery of the tubes. The lander is equipped with a sample transfer arm built by ESA for the job.

Of course, scientists don't want to leave anything to chance. So, the mission also has a backup plan in case Perseverance can't deliver. Mission scientists will send a couple of small helicopters out to gather the samples.

We know that could work because the Ingenuity chopper has been cranking away in overtime, showing scientists just what a Mars chopper can do.

Once the rocks are onboard the SRL, they'll get loaded into a small rocket that will take off from the surface.

Once in space, it will deliver them to an ESA-built spacecraft orbiting Mars for eventual return to Earth. If all goes well, the rocks are expected to be in labs for more detailed study sometime in 2033.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.