Diamond is well-known for being the hardest natural material on Earth, though synthetic forms have been developed that are even tougher – a feat that researchers have managed again, through a new approach to diamond formation.

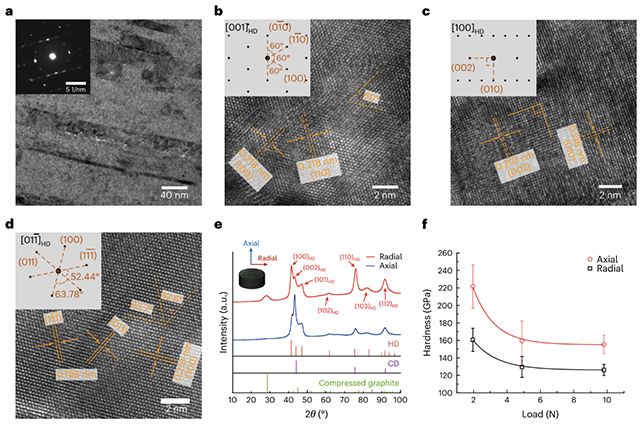

The team put graphite (another super-hard material) under an intense amount of pressure, before heating it to 1,800 K (that's 1,527 °C or 2,780 °F). The resulting diamond has a hexagonal lattice crystal structure, rather than the normal cubic structure.

Hexagonal diamond (or lonsdaleite) was first brought to the attention of scientists more than 50 years ago, after it was discovered in a meteorite impact site. The new research is the first solid evidence that this internal structure boosts hardness.

"Natural and synthetic diamonds mostly have a cubic lattice, whereas a rare hexagonal structure – known as hexagonal diamond (HD) – has been largely unexplored due to the low purity and minuscule size of most samples obtained," write the researchers in their published paper.

"The synthesis of HD remains a challenge and even its existence remains controversial."

The newly produced diamond has a hardness of 155 gigapascals (GPa), which is essentially a pressure measurement: the pressure the material can withstand. Natural diamond, by comparison, tops out at around 110 GPa in hardness.

Thermal stability is impressive too. The synthetic hexagonal diamond can stay intact up to at least 1,100 °C (2,012 °F), the researchers report, compared to 900 °C (1,652 °F) for nanodiamonds often used in industrial applications. Natural diamond can withstand greater temperatures, but only in a vacuum.

As well as overcoming some of the limitations that researchers have previously come up against when synthesizing hexagonal diamond, the team was able to identify ways the process could be scaled up in the future.

"We discovered that when graphite is compressed to much higher pressures – as only rarely explored previously – hexagonal diamond is preferentially formed from post-graphite phases when heating is applied under pressure," write the researchers.

There's a lot more work to do before this kind of diamond can be produced at a large scale, but the hardness and thermal stability readings of this first batch suggest the material holds promise for use in drilling, machinery, or data storage.

It's not the first time scientists have tried to create hexagonal lattice diamonds in the lab. A previous project carried out in 2016 created these diamonds from amorphous carbon, a material without a set form.

Now that another method of synthesis has been carried out in the lab – and proven to create an ultra-hard diamond material – research can continue into how to make the most of this rare substance.

"Our findings offer valuable insights regarding the graphite-to-diamond conversion under elevated pressure and temperature, providing opportunities for the fabrication and applications of this unique material," write the researchers.

The research has been published in Nature Materials.