A new type of time crystal could represent a breakthrough in quantum physics.

In a diamond zapped with lasers, physicists have created what they believe to be the first true example of a time quasicrystal – one in which patterns in time are structured, but do not repeat. It's a fine distinction, but one that could help evolve quantum research and technology.

"They could store quantum memory over long periods of time, essentially like a quantum analog of RAM," says physicist Chong Zu of Washington University in the US. "We're a long way from that sort of technology. But creating a time quasicrystal is a crucial first step."

Time crystals, predicted in theory by US theoretical physicist Frank Wilczek in 2012 before being observed for the first time in 2016, add a little something extra to the patterned atomic matrix that makes up regular solids.

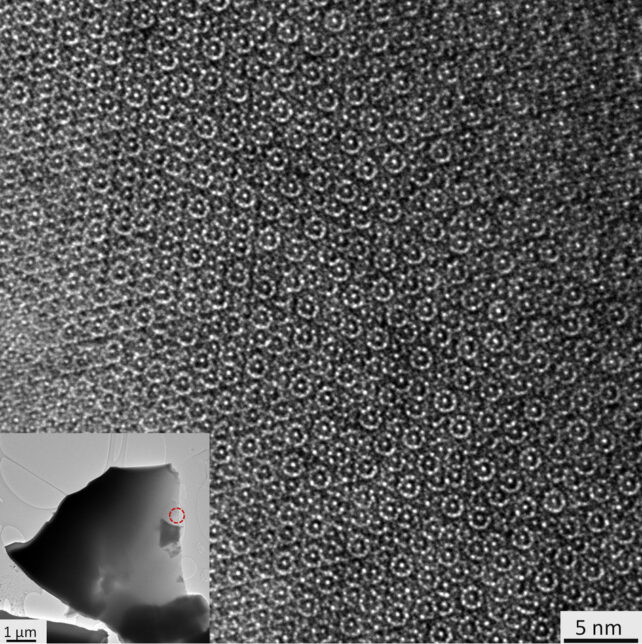

Crystalline materials like diamond, quartz, and salt take the form of three-dimensional atomic lattices, where the arrangement of the particles therein repeats. You can take any section of the lattice and superimpose it over another and it will match up perfectly.

A time crystal is a material in which particles move through sequences that aren't dictated by the timing of any external push. The particles oscillate between energy states with a timing pattern that repeats in such a way that it can be perfectly superimposed, as seen in the video below.

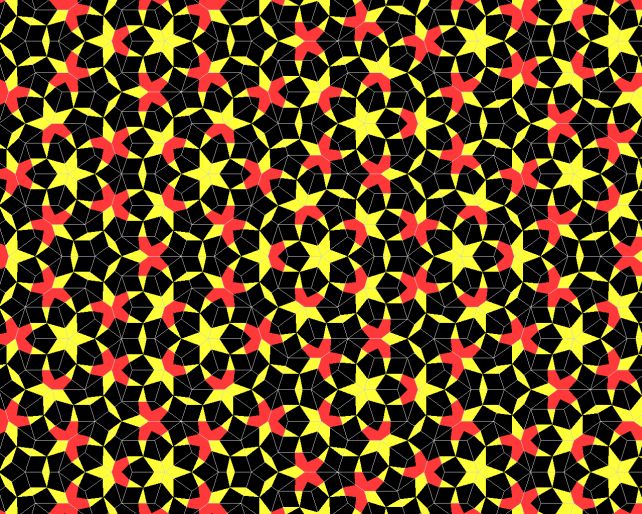

A quasicrystal, by contrast, is one in which the particles form a structured, but non-repeating pattern, like a Penrose tiling or Ammann-Beenker tiling. At first glance it might look like it repeats, but its components will not perfectly superimpose.

Time crystals have been experimentally observed a number of times, using different materials. Now, a team of physicists led by Guanghui He of Washington University and Bingtian Ye of Harvard University has created what they believe is the first time quasicrystal. The temporal patterns of the oscillating particles have structure, but don't repeat.

"It's an entirely new phase of matter," Zu says.

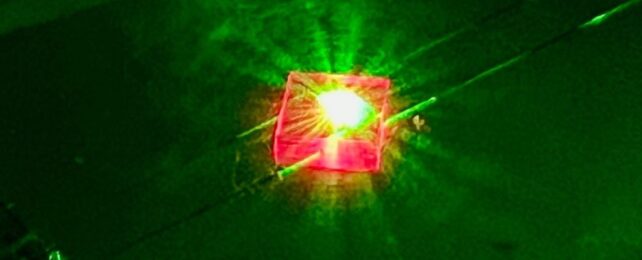

One way of creating a time crystal is to knock some of the carbon atoms out of the crystal lattice of diamond, creating what is known as a nitrogen-vacancy center, which is a neighboring nitrogen atom and an empty space. This is the technique the researchers used to create and investigate the properties of a time quasicrystal.

They used nitrogen lasers to knock a bunch of carbon atoms loose in a millimeter-wide chunk of diamond, giving electrons some elbow room to dance about to the beat of microwave pulses, under the quantum influence of their neighbors.

Structuring the microwave's rhythm in non-repeating patterns resulted in a similar but independent behavior in the oscillating particles, one that met the criteria of a time crystal.

"We used microwave pulses to start the rhythms in the time quasicrystals," Ye says. "The microwaves help create order in time."

The researchers observed this dance for hundreds of cycles before the time quasicrystal broke down, as time crystals are wont to do: they are extremely sensitive and vulnerable to external interference.

"We believe we are the first group to create a true time quasicrystal," He says.

The results offer new insights that can help us better understand the quantum realm, as well as time crystals themselves. There are potential practical applications, too, such as in the science of metrology, or measuring things. One day, time crystals could help measure time.

They could also be used for quantum sensors and quantum computing (of course). That's probably quite a long way off; but a journey can only be made by taking steps through time.

The research has been published in Physical Review X.