You don't want to ever get too close to a piranha, but if you did, you'd notice something rather strange: these freshwater fish shed their old teeth in groups, one side of the mouth at a time, with new teeth growing in as replacements simultaneously.

A new study has found that an interlocked half mouth of new teeth wait in 'crypts' underneath the old teeth, allowing them to instantly take over once the previous teeth fall out.

The researchers who discovered this rather unusual odontological manoeuvering – which happens several times in a piranha's life – say it might have evolved from the piranha's main needs to guard against tooth loss, and always ready for feeding.

Previous research had already established that piranhas lost their teeth one side of the mouth at a time, but the exact mechanism for how they were being replaced had remained a mystery until now – no museum specimens had ever appeared showing the creatures with half a mouth of teeth missing.

(University of Washington)

(University of Washington)

"I think in a sense we found a solution to a problem that's obvious, but no one had articulated before," says biologist Adam Summers, from the University of Washington.

"The teeth form a solid battery that is locked together, and they are all lost at once on one side of the face. The new teeth wear the old ones as 'hats' until they are ready to erupt. So, piranhas are never toothless even though they are constantly replacing dull teeth with brand new sharp ones."

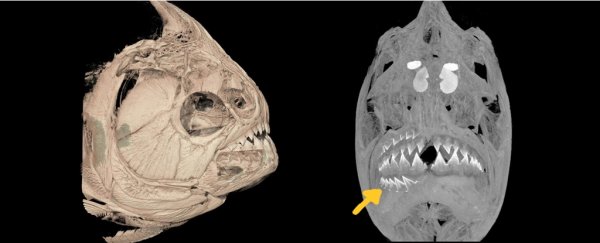

Using detailed computed tomography or CT scans, the team looked at 93 deceased specimens of piranhas and their plant-eating cousins pacus, sampled across 40 species.

By adding in other types of imaging, tissue staining, hereditary analysis, and the study of fish specimens being held in museums, a detailed picture of what was happening began to appear: as the old teeth wear out, new ones wait in a sort of 'crypt' underneath.

Additionally, the rows of teeth form a strong interlocking block, according to the researchers, and this helps to explain why the fish still shed teeth in groups and haven't developed the habit of losing them individually.

(Frances Irish/Moravian College)

(Frances Irish/Moravian College)

"When one tooth wears down, it becomes hard to replace just one," says biologist Matthew Kolmann, from George Washington University.

"Once you link teeth together, if one wears too much, it becomes like a missing link in an assembly line. They all have to work together in a coordinated way."

With a diet that can rely on being able to chomp through flesh, scales, bones, plants and more, these fish don't want to be left without a set of sharp teeth to call upon – and this newly discovered replacement process makes sure that's the case.

Having teeth interlocked together likely gives piranhas extra stability when chewing, as the stress is more evenly spread out. There is some variety, though, in the locking mechanisms used by different piranhas and pacus.

There are still questions to be asked here – for example, is it the new teeth pushing upwards, or the old teeth finally wearing out, that triggers the switch? Scientists will have to run further studies to find out, but part of the success of this current study has been in showing that museum collections still have scientific value.

"The motivation for this work came out of an effort to take those collections and come up with new ways of learning about the biology of fish," says Kolmann.

The research has been published in Evolution & Development.