If we manage to reach the climate target set by the Paris Agreement, we could be living in a world that is, on average, 2 degrees Celsius hotter than preindustrial levels by the end of this century, and even then, there'll be far fewer places to live comfortably on this planet we call home.

The average global temperature has already risen by 1.5 °C above preindustrial levels. We reached this grim milestone just last year.

Now scientists report that adding 0.5 °C of extra heat to the global average will triple the area of land on our planet too hot for even a healthy adult human to inhabit. That's equivalent to writing off a landmass about the size of the United States.

For people over 60, whose bodies are even more vulnerable to extreme heat, that danger zone will span about 35 percent of Earth's landmass, a steep incline from the 21 percent that's off-limits to them today.

It's something we might need to prepare for, especially because these projections lie at the milder end of global warming scenarios.

"Our findings show the potentially deadly consequences if global warming reaches 2 °C," says climate scientist Tom Matthews from King's College in London.

"At around 4 °C of warming above preindustrial levels, uncompensable heat for adults would affect about 40 percent of the global land area, with only the high latitudes, and the cooler regions of the mid-latitudes, remaining unaffected."

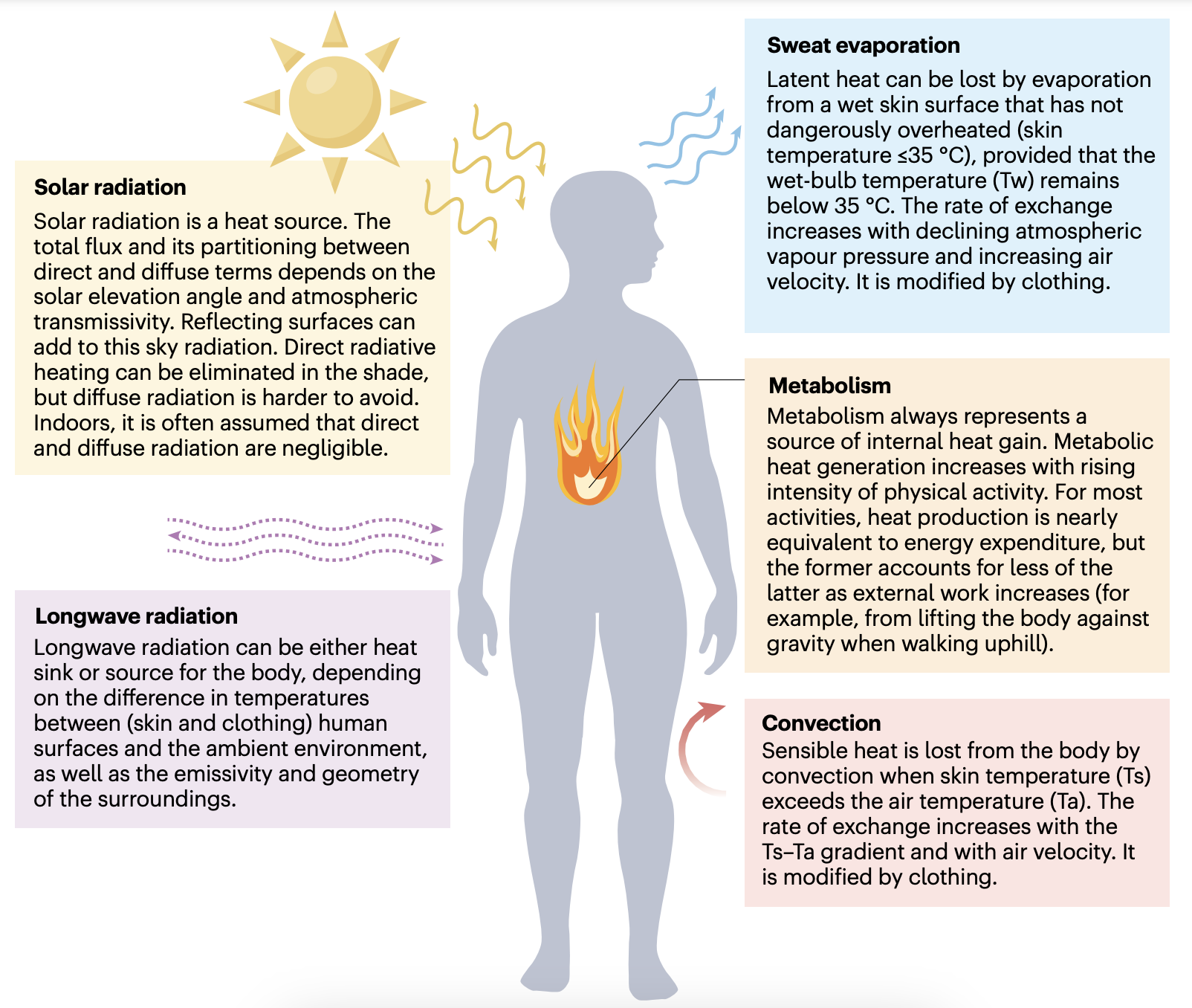

Even at our healthiest, our bodies can only cope with so much, but what 'coping' actually means is pretty broad. Being hot enough to sweat and get sleepy might not kill you, but you're not exactly thriving in those circumstances either.

Beyond that, there's 'uncompensable' heat, where there's more heat going into your body than its mechanisms to stabilize internal temperature can keep up with. It's an issue faced by people in fairly extreme conditions, often exacerbated by personal protective equipment (PPE): firefighters and athletes, for example. But it's getting more common in heat waves, too, especially around the equator.

Depending on where you live, you might already have a sense of this. In recent years, regions like the Persian/Arabian Gulf, the Indo-Gangetic Plain, and even isolated hotspots in the southern US, Mexico, and Australia, have experienced extreme heat events that breach even young adults' uncompensable limits.

Then there's unsurvivable heat, which is enough to kill you. In this study, it was defined as the body's core temperature – usually a balmy 37 °C – reaching 42 °C in six hours or less. At 2 °C warming above preindustrial levels, unsurvivable thresholds will be breached in certain areas only for adults over 60.

But if we continue to emit fossil fuels and destroy the ecosystems that absorb atmospheric carbon, accelerating global warming, we won't flatten the curve enough to make that 2 °C target. At 4-5 degrees above preindustrial levels, the report concludes, heat reaches life-threatening highs for people of any age in some regions.

Adults over 60 years could experience uncompensable heat across 60 percent of the Earth's surface, and unsurvivable heat becomes a risk for people of any age in the tropics (which is where more than 40 percent of the entire human population currently lives).

"Unsurvivable heat thresholds, which so far have only been exceeded briefly for older adults in the hottest regions on Earth, are likely to emerge even for younger adults," says Matthews.

"In such conditions, prolonged outdoor exposure – even for those in the shade, subject to a strong breeze, and well hydrated – would be expected to cause lethal heatstroke. It represents a step-change in heat-mortality risk."

Evidence suggests we will need to limit global warming, by switching to renewable energy sources and protecting important carbon reserves, to avoid the worst of these predictions. But Matthews says we also need to prepare for a world where, in many places, being outdoors is a health risk.

"As more of the planet experiences outdoor conditions too hot for our physiology, it will be essential that people have reliable access to cooler environments to shelter from the heat," he says.

The research was published in Nature Reviews Earth and Environment.