If you had asked a botanist just a few years ago how many plant species have perished in modern times, their estimate would probably number fewer than 150. The most exhaustive study thus far has now quadrupled that amount.

Ever since 1753, when Carl Linnaeus "the father of modern taxonomy" put together his classification of plant species, roughly 571 of them have gone extinct.

What's more, the authors of the new study claim that since 1900, an average of three plant species has disappeared each year. That's an extinction rate at least 500 times faster than is naturally expected, and twice the total number of extinctions seen in amphibians, mammals and birds combined.

The comprehensive study is the first global analysis on modern extinction rates to include plants, and thanks to a sheer lack of data, the researchers are "quite sure" they've underestimated the reality.

"We suffer from plant blindness," plant biologist Maria Vorontsova told The Guardian.

"Animals are cute, important and diverse but I am absolutely shocked how a similar level of awareness and interest is missing for plants. We take them for granted and I don't think we should."

Analysing actual extinctions rather than estimates, the researchers at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew have discovered that fewer than half of all reported plant extinctions are actually accurate.

The Extinction Red List kept by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, for instance, is well off the mark. Of the 122 extinct plant species currently on this list, the authors of this study found no less than 50 have been rediscovered or need to be reclassified.

Even worse, the list appears to be missing 491 extinctions.

The results are based on a previously unpublished database of plant extinctions kept by Kew Gardens in the UK, incorporating three decades-worth of literature reviews and fieldwork reports.

On the surface, the data suggests that only 0.2 percent of plant species have gone extinct, compared to 5 percent of birds and mammals. This, however, is not the full picture. Unlike animals, the average extinction lag time for plants is much longer, which means it takes them longer to become fully (and not just functionally) extinct.

"This is consistent with 89 [percent] of rediscovered species having high extinction risk, with several being known from only a few surviving individuals," the authors explain.

"Therefore, our estimated extinction rate, while elevated, is still likely to prove an underestimate of ongoing extinction of plant diversity."

(Humphreys et al, Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2019)

(Humphreys et al, Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2019)

The pattern of modern extinction in plants is strikingly similar to that of animals, though it doesn't seem to be based on evolutionary patterns, as it is with the latter.

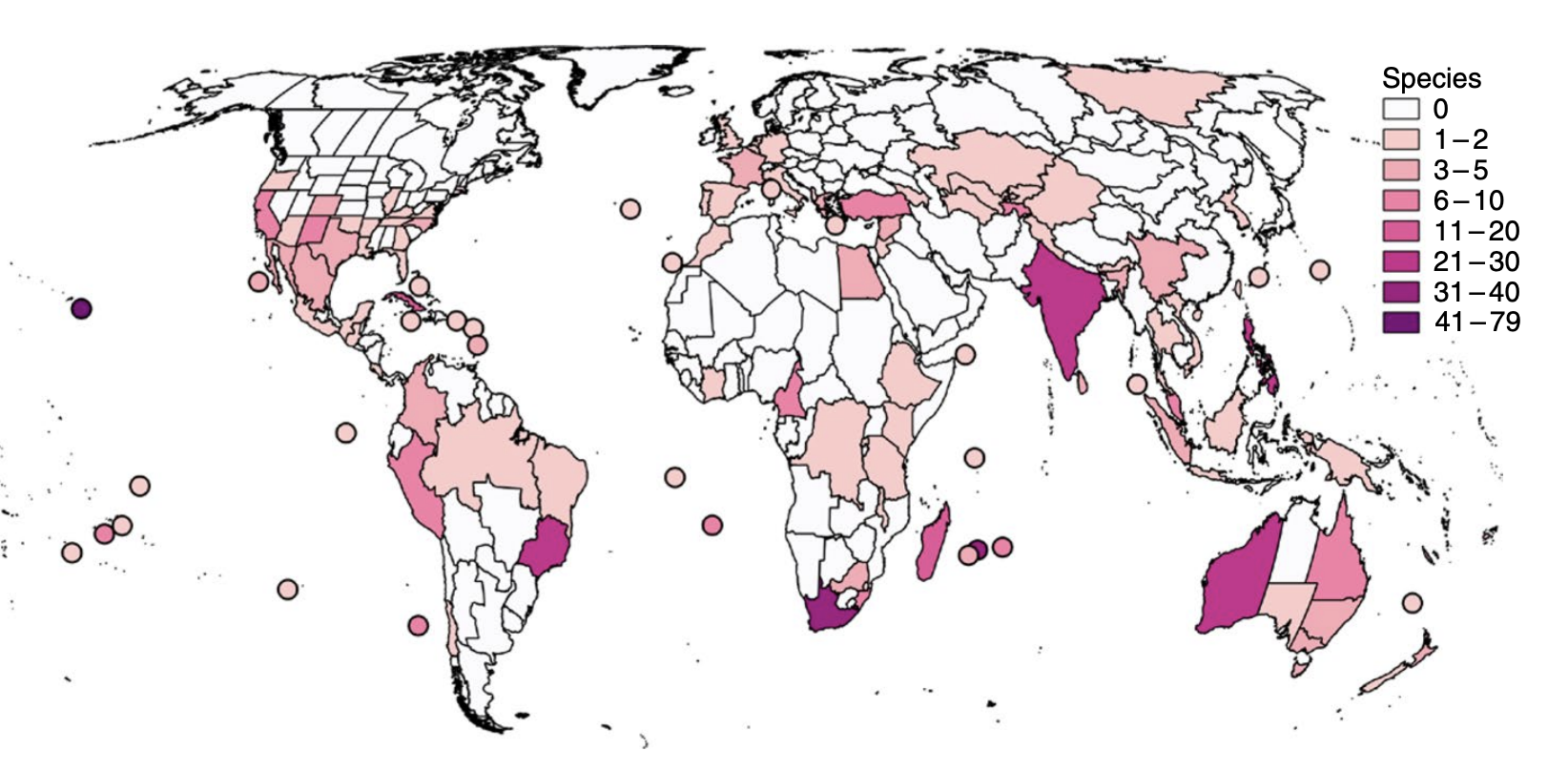

Today, it appears that a majority of plant extinctions are occurring in biodiversity 'hotspots' in the Tropics and the Mediterranean, including places like Australia, India, and Hawaii. Of all the extinct plant species numbered throughout the world, half were once found on an island and 18 percent once flourished in the Pacific.

"This probably reflects the high proportion of unique species (endemics) in island biotas and their vulnerability to biological invasion," the authors suggest.

The patterns, however, could also be due to human bias. After all, the researchers admit, our collective knowledge so far is almost entirely based on plants that have been historically useful to humans.

This is no more obvious than when looking at what's known as rediscovery rates. In the past three decades, roughly 300,000 plant species have been added to the Kew Gardens database, and each year, we find about 16 plants that we once thought had gone extinct.

Still, the rediscovery of plant species is unlikely to lower the 'frightening' rates put forward by researchers at Kew. Most of the 571 plants have been extinct for a long time, and rediscovery on islands is far less likely than on continents.

Besides, the authors argue, many new species are no doubt headed for the list. With habitat loss, climate change and human exploitation, newly-described plants could very well have higher rates of extinction, and some could even disappear before we know they exist.

"Scientists have not studied the vast majority of the world's plants in any detail, so the authors are right to think the numbers they have produced are large underestimates and there are likely to be extinctions that have been overlooked," says Alan Gray, a plant ecologist who was not involved in the study.

Because millions of other species, including our own, depend on plants for survival, Gray says we need to start asking not what biodiversity can do for us, but what we can do for biodiversity.

The research was published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.