By Earth's standards, you could hardly imagine a stranger world than frigid, tiny Pluto. It resides in the far corner of the Solar System at an average of about 4 billion miles from the sun.

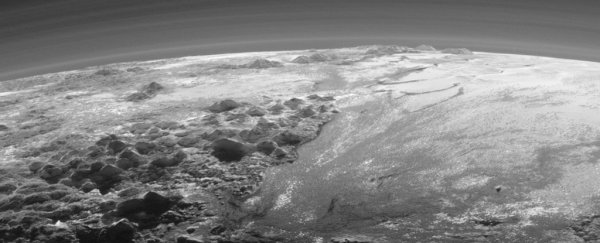

NASA's New Horizons probe, which flew within 7,800 miles (12,500 km) of the dwarf planet in July 2015, gave us the best look at Pluto yet. There, temperatures plunge to minus 380 Fahrenheit (-230 C). At Plutonian noon, the sunlight is comparable to Earth's dusk.

But perhaps the most surprising outcome of New Horizons' journey was not the deeper peek into Pluto's oddities. The spacecraft also uncovered Pluto's versions of familiar geography.

Like Earth, Pluto has jagged mountains, sweeping plains and changing seasons. A new study published Thursday in the journal Science reveals another feature shared across billions of miles: Pluto has dunes.

This world, where the gravity is one-sixteenth as strong as Earth's, is "so different from our own in so many ways," said study author Matthew Telfer, an expert in physical geography at Britain's University of Plymouth.

But the dunes, he said, show that Pluto "is actually so similar."

NASA released New Horizons images shortly after the flyby, including an famous picture of a heart-shaped basin on Pluto. In the western lobe of that heart, a plain called Sputnik Planitia, Telfer and other planetary scientists spotted something peculiar.

Where Sputnik Planitia approaches mountains of ice, its surface ripples.

To Telfer and other planetary scientists, those ripples looked like windswept sand - a bit of a puzzle, because scientists weren't sure whether Pluto's thin atmosphere could muster enough wind for sweeping.

Brigham Young University planetary scientist Jani Radebaugh, an author of the new study, recalled seeing the features in New Horizons images posted to Facebook.

"They just really looked like dunes," she said. No other team had plans to investigate the formations, so she joined up with Telfer and members of the New Horizons mission.

The first reports of possible dunes - as the New Horizons scientists were careful to qualify them in 2015 - did not pan out.

"There're a bunch of things out there that are vaguely dunelike," Telfer said. But in one area of the plain, the evidence kept piling up.

"It's an exciting discovery, I'll say that for sure," said Ryan Ewing, a geologist at Texas A&M University who was not involved with this report. "The way that they're recognizing the dunes on the surface is the same technique we've used to identify dunes on Mars."

To build a dune requires sand and wind. Quartz fragments commonly supply the sand for Earth dunes. Pluto's Sputnik Planitia is capped with nitrogen ice, which the scientists estimated would not be sturdy enough to form dunes.

Frozen nitrogen, Radebaugh said, has a consistency that resembles toothpaste.

But solid methane sits atop this toothpaste glacier, too. Methane ice breaks into tiny particles. The scientists calculated that the methane grains are probably a hundredth of an inch in diameter.

To hold a handful of methane grains, if you could handle the cold, would be like scooping up "really fine sand," Radebaugh said.

Walking on these dunes would be "pretty much like walking through sand on a dune on Earth, we reckon," Telfer said. (If you'd feel anything through the well-insulated soles of your spacesuit, that is.)

Pluto's dunes rise to about 100 feet, roughly as high as the Mesquite Flat Dunes in Death Valley National Park. Streaks on the surface indicate the wind blows in a perpendicular direction to the dunes.

"The paper makes a very compelling case these are dunes," which have the necessary spacing and orientation, said William B. McKinnon of Washington University in St. Louis, who studies the geology of worlds in the outer Solar System and was not an author of this report.

Yet the sand must flow. A model of Pluto's climate suggests that the wind can get as fast as about 20 mph (32 km/h). That's enough to sculpt floating particles into a dune shape.

"This is one of the windiest spots on Pluto," Telfer said, "and the winds are in exactly the right direction."

But those winds are too gentle to kick up methane grains, normally packed close together, from the surface.

It's a little bit like flying a kite on a calm day: A running start is needed to lift the kite off the ground, where a weak breeze can carry it. Something else has to give the dune grains that initial boost.

The study authors suspect a process called sublimation did the trick.

On Earth, we're more familiar with evaporation - when you get out of the ocean and walk along the beach, the sun dries you, turning liquid water to vapor.

On Pluto, the sun turns solids directly into gas. Telfer and his colleagues spotted pits along the edge of the plain, where they suspect nitrogen ice sublimated.

Nitrogen sublimation would be powerful enough to fling up methane grains, Telfer said, providing Pluto's winds with the airborne ingredients for a dune.

McKinnon said the sublimation theory was "somewhat speculative". He said other explanations, such as periodic increases in Pluto's atmospheric pressure, could also result in lofted dune particles.

The crucial finding, in Radebaugh's view, is that the dunes exist. With its dunes, Pluto joins a club that includes Earth, Mars, Venus, Saturn's moon Titan and, possibly, a comet.

"All we have to do is turn a spacecraft to a body and look at a region we have not seen before, " Radebaugh said, and a whole new realm of discovery opens.

For New Horizons, that opening will come on New Year's Day 2019, when it cruises to an object in the Kuiper belt called 2014 MU69, nicknamed Ultima Thule - meaning beyond the borders of the known world.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.