Oscar-Claude Monet was a vital founder of the impressionist art movement in the 19th century, and some scientists now think the French painter's revolutionary style was heavily influenced by air pollution.

At the beginning of his career, Monet painted cities and landscapes that sharply contrasted with the sky. As the fallout from the Industrial Revolution heated up, however, the artist's perspective grew hazier and his palette became paler.

Climate scientists have now shown that those changes mirror the atmospheric conditions of the time. The research was led by Anna Lea Albright from Sorbonne University in Paris and Peter Huybers from Harvard University.

"Our basic premise is that Impressionism – as developed in the works of Turner, Monet, and others – contains elements of polluted realism," the authors write.

To cover the entire length of the Industrial Revolution as well as the period following, researchers focused on two artists who were prolific painters of skies in the 19th century: Monet and his predecessor, the British painter Joseph Mallord William Turner.

Air pollution is caused by an increase in toxic microscopic particles that become suspended in the atmosphere. During the Industrial Revolution, most of these emissions came from coal plants.

Because particles of soot can absorb and scatter sunlight, air pollution can dull colors and blur edges when looking into the distance. Modern–day photos of a polluted skyline, for instance, show 19 percent less contrast on average than photos of clear skylines.

Applying this analytical technique to paintings has now allowed researchers to predict how much contrast should be expected based on coal emissions.

For Monet, the authors examined 38 paintings produced between 1864 and 1901. For Turner, they looked at 60 oil paintings composed between 1796 and 1850.

"Across Turner's works, a progression is visually apparent from sharp to hazier contours, more saturated to pastel-like coloration, and figurative to impressionistic representation," the authors write.

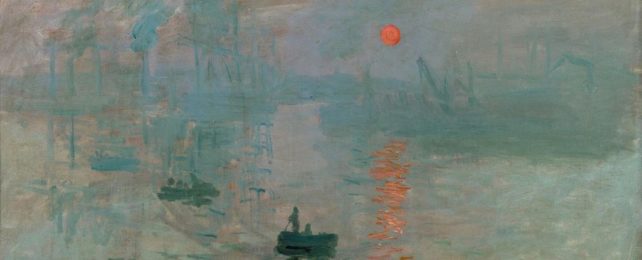

"A similar progression is evident across Monet's works."

While most of Turner's paintings feature England, the Monet paintings considered by researchers are of Paris and London. Historical coal emissions in both those cities closely track with the artist's move to a more impressionist style.

The low contrast used by Monet later in his career, for instance, matches the high emissions in London at the end of the 19th century.

In Early Monet paintings, visibility averages about 24 kilometers (15 miles). But for Monet's daytime paintings in London, visibility averages just 6 kilometers.

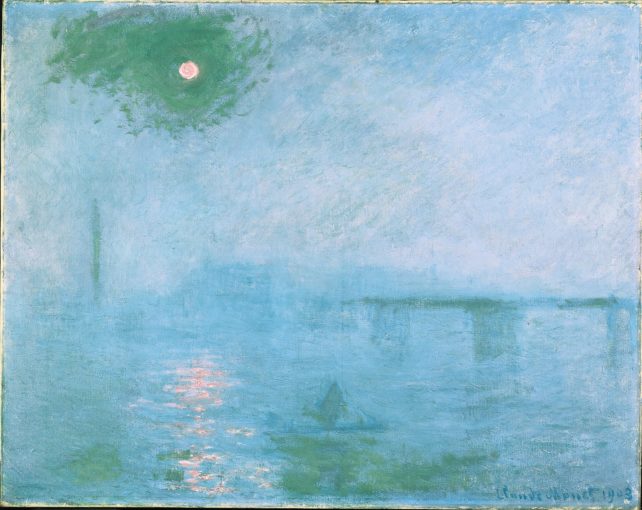

His paintings of Charing Cross Bridge are particularly hazy. They have an average visibility of just 1 kilometer. That might sound extreme, but in the thick of the 'London Fog', an official inquiry described winter visibility in 1901 as never more than 2 kilometers.

There's even a chance that Monet actively painted on smoggy days. His letters detail painting sessions in the year 1900 that align with daily weather reports of low wind and rain – conditions that tend to suit air pollution.

Monet even wrote, "what I like most of all in London is the fog", and "when I got up I was terrified to see that there was no fog, not even a wisp of mist: I was prostrate, and could just see all my paintings done for, but gradually the fires were lit and the smoke and haze came back".

It is clear, Albright and Huybers argue, that environmental changes are rendered in artwork, even when those changes aren't caused by humans.

Turner, for instance, began a series of watercolor sunsets in the years following the Tambora volcanic eruption in 1815, which emitted a whole bunch of particles into the atmosphere that reddened the sky.

"Indeed," the authors write, "19th century art critic John Ruskin wrote about Turner's work that 'had the weather when I was young been such as it is now, no book such as 'Modern Painters' ever would or could have been written'.

The same could be said of many other artists, too. The current model that researchers have put together works for more than Monet and Turner.

Albright and Huybers have also successfully applied it to the work of Gustave Caillebotte (1848 to 1894), Camille Pissarro (1830 to 1903), Berthe Morisot (1841 to 1895), and James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834 to 1903).

This doesn't mean air pollution can explain the progression of all historic painters, but it certainly seems to be a powerful influence for many.

Painters like Edgar Degas, for example, might have painted with a hazier palette as their eyes grew weaker over time. But Monet started painting in an impressionist style years before he developed cataracts. Air pollution probably influenced his style more than old age.

"Our view is that impressionistic paintings recording natural phenomena – as opposed to being imagined, amalgamated, or abstracted – does not diminish their significance," the authors conclude.

"Rather, it highlights the connection between environment and art. "A connection that still persists to this day.

The study was published in PNAS.