In early September 1859, something world-changing occurred. Earth was wracked by a monumental solar storm, which lashed our magnetosphere with a coronal mass ejection, the like of which had never before occurred in recorded history.

It's called the Carrington Event, and it occurred right on the cusp of the Technological Revolution. It temporarily knocked out telegraph systems, but we weren't yet so reliant on electrical technology that the storm could play major havoc.

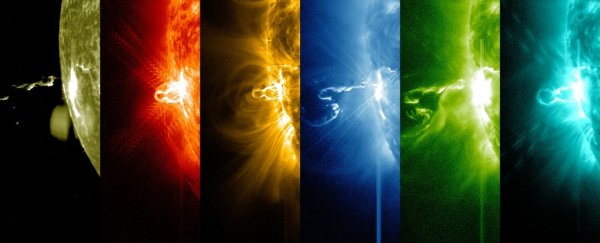

And yes, solar storms can really mess us up. When charged particles from the Sun slam into Earth's magnetosphere, the interaction can cause a geomagnetic storm, generating currents and atmospheric disturbances and ionisation that can knock out power grids and disrupt communications and navigation.

If a solar storm on a Carrington Event scale were to hit Earth today, we could be in big trouble. And although we haven't been hit by one that big since, astrophysicists now believe solar storms of that magnitude are not as uncommon as we thought.

In fact, researchers think the Sun could be throwing a Carrington Event-style party every few decades - and it's only a matter of time before we're caught in the disco ball again.

"The Carrington Event was considered to be the worst-case scenario for space weather events against the modern civilisation," explained astrophysicist Hisashi Hayakawa of Osaka University.

"If it comes several times a century, we have to reconsider how to prepare against and mitigate that kind of space weather hazard."

Although the Carrington Event is well studied and characterised, Hayakawa and his team realised something was missing. The scientific and historical analyses focused on the Western hemisphere, leaving half a planet's worth of records out of the picture.

So, the international collaboration set about collecting as many historical records of the storm's auroras from the Eastern hemisphere and Iberian Peninsula as they could lay hands on. These included Russian observatory logs, diary entries, newspaper reports, and historical records from East Asia.

They also managed to retrieve unpublished observational logs and manuscripts from Europe, including drawings of the sunspot group whose intense magnetic fields are thought to have produced the coronal mass ejection associated with the storm. By studying these drawings, the researchers were able to track the evolution of the storm over time.

The drawing below, from a Royal Astronomical Society manuscript by German astronomer Heinrich Schwabe, shows the sunspots visible on 27 August (left), 1 September (middle) and then a closeup of the 1 September sunspot group (right).

(Hayakawa et al., Space Weather, 2019, courtesy Royal Astronomical Society)

(Hayakawa et al., Space Weather, 2019, courtesy Royal Astronomical Society)

These records were then compared to the Western published records, such as ship logs, scientific publications, and newspaper reports.

Through this comprehensive analysis, the team discovered something new about the Carrington Event; namely, that it wasn't just one huge belch of plasma. Rather, the team believes that the sunspot group erupted several times over the weeks before and after the event itself, from an earlier coronal mass ejection on 27 August 1859, and continuing through early October.

The August eruption produced a smaller solar storm that could, the researchers said, have contributed to the severity of the September event.

Since the team now had the most complete reconstruction ever made of the Carrington Event, they then set about comparing it to other notable storms, such as the storm of February 1872, which produced spectacular auroras widely reported in newspapers around the world; the storm of May 1921 that wiped out telegraph services in the US; the August 1972 storm that may have detonated sea mines; and the storm of March 1989 that wiped out a Canadian power grid.

The team found that, in particular, the 1872 and 1921 storms bore strong similarities to the Carrington Event. And let's not forget the solar storm of July 2012 - a colossal coronal mass ejection that mostly missed Earth, but would have been Carrington-scale if we were in its path.

All this suggests that the severity of the Carrington storm is not uncommon, and that we may have just been lucky so far.

"The initial comparison reveals that the Carrington Event is probably not the exceptional extreme storm, but one of the most extreme magnetic storms," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"While this event has been considered to be a once-in-a-century catastrophe, the historical observations warn us that this may be something that occurs more frequently and hence might be a more imminent threat to modern civilisation."

The research has been published in Space Weather.