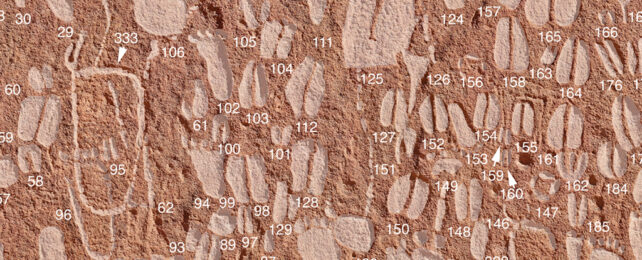

The animal footprint carvings you can find in the Doro Nawas Mountains of western Namibia are quite something: the artists have captured the tracks so accurately, they can reveal plenty of useful information about the animals they represent.

A team from the Heinrich Barth Institute and the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany, and the Nyae Nyae Conservancy in Namibia, worked with Indigenous tracking experts from the Kalahari region to look at a total of 513 carvings.

For more than 90 percent of them, Indigenous experts could identify the species, sex, age group, and even which leg the carving was from. It's like a wildlife compendium, written in rock.

"The study represents further confirmation that Indigenous knowledge, with its profound insights into a range of particular fields, has the capacity to considerably advance archaeological research," write the researchers in their published paper.

Animal and human footprints often feature in prehistoric cave art – there are hundreds of them in this particular collection – but what's not clear is why the artists of ancient times wanted to get these tracks on the record.

One idea is that they could have been used as a teaching aid. However, the locations of some of the engravings, the height at which they're placed, and the general darkness of the caves mean they wouldn't make ideal classrooms. The researchers couldn't come up with a suitable hypothesis that completely made sense for these rock carvings.

What is clear is that the expertise offered by Indigenous people can be vital in unlocking the secrets found in archaeological digs. The tracking experts consulted here have all been involved in other studies of ancient rock art in the past.

The engravers of long ago showed particular preferences for certain types of animals – including giraffes, rhinos, and leopards – and were more likely to depict fully grown adults than juveniles, and males rather than females.

The number of human footprints included in the rock gallery is greater than other similar sites, and most are of juveniles. There is also an unusual absence of domestic animals and reptiles.

All these discoveries are made possible because of the accuracy of the art itself – and the local expertise deployed to catalog it.

These particular engravings come from the Late Stone Age, beginning some 50,000 years ago. While some of them are records of animals that still inhabit the region, others are no longer there, giving researchers an indication of how the climate of the area may have changed over time.

While interpreting cave art can be challenging without speaking to the engravers themselves, these depictions give us an invaluable window into the past, providing a glimpse into how human society and the animal kingdom once lived together.

"The features investigated in this study, taken together, point to the tracks being endowed with complex meanings," write the researchers.

"Attaining even an approximation of these would require researchers to call upon ethnographic data and Indigenous knowledge – a necessity of which future research would do well to take heed."

The research has been published in PLOS ONE.