Mosasaurs were the apex predators of the oceans during the reign of the dinosaurs, but new research reveals dinosaurs weren't safe from them in rivers either.

Researchers from Sweden, the US, and the Netherlands analyzed isotopes in several mosasaur teeth from sites across North Dakota, confirming that these ancient sea monsters could also live in freshwater environments.

Related: Prehistoric Air Has Been Reconstructed From Dinosaur Teeth in an Amazing First

Judging by the features of a tooth found in an inland floodplain, it belonged to a group of mosasaurs that may have grown to a length of around 11 meters (36 feet).

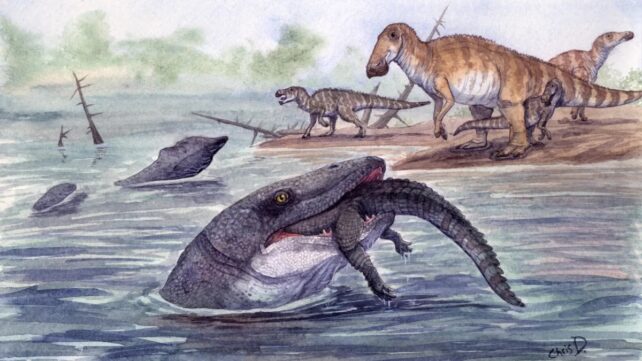

That adds a terrifying new element of danger to gathering at watering holes – thirsty dinosaurs had to be on alert not only for terrestrial threats, but also for bus-sized predators lurching out of the water itself.

"The size means that the animal would rival the largest killer whales, making it an extraordinary predator to encounter in riverine environments not previously associated with such giant marine reptiles," says Per Ahlberg, vertebrate palaeontologist at Uppsala University in Sweden.

Mosasaurs were carnivorous, aquatic reptiles that lived during the late Cretaceous period. While some species were small, most of them were giants, allowing them to dominate the ancient oceans for millions of years.

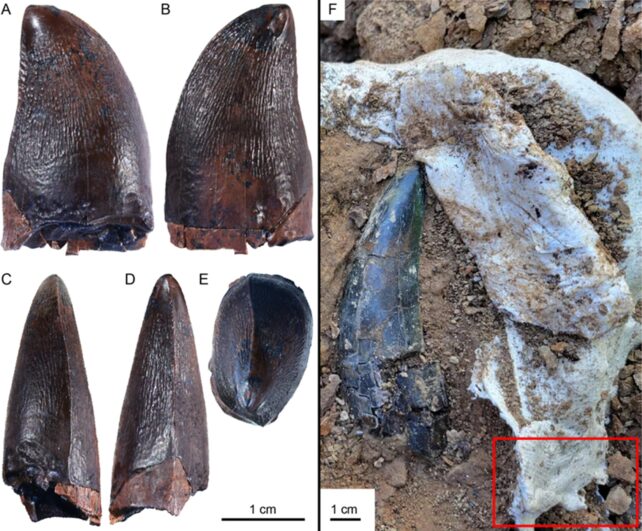

That's why it was strange then, when in 2022 paleontologists discovered a mosasaur tooth in an inland floodplain, alongside a Tyrannosaurus rex tooth and a crocodylian jawbone. Did its owner live there, in the freshwater riverine environment, or had it perhaps washed in from the ocean?

To find out, the researchers conducted an isotope analysis of the tooth's enamel, and compared it with similar signatures in other fossil specimens including shark teeth and ammonites.

Elements can come in multiple variations, known as isotopes, differentiated by the number of neutrons in the atom. Studying the ratios of isotopes in a sample can reveal what an animal ate and where it lived.

In this case, the researchers examined the ratios of oxygen, strontium, and carbon isotopes.

Oxygen, for instance, is particularly useful for differentiating between saltwater and freshwater environments: the lighter isotope 16O is more likely to evaporate from the ocean and fall as rain, meaning freshwater environments have more 16O and much less of the heavier 18O isotope, compared to seawater.

And sure enough, the signature of oxygen and strontium isotopes in the mosasaur tooth indicated that the animal was perfectly at home in the freshwater environment.

"When we looked at two additional mosasaur teeth found at nearby, slightly older, sites in North Dakota, we saw similar freshwater signatures," says Melanie During, vertebrate paleontologist at Uppsala.

"These analyses show that mosasaurs lived in riverine environments in the final million years before going extinct."

The carbon isotope ratio backed up the story, adding a chilling new detail: this river monster wasn't averse to eating dinosaurs.

"Carbon isotopes in teeth generally reflect what the animal ate," says During.

"Many mosasaurs have low 13C values because they dive deep. The mosasaur tooth found with the T. rex tooth, on the other hand, has a higher 13C value than all known mosasaurs, dinosaurs, and crocodiles, suggesting that it did not dive deep and may sometimes have fed on drowned dinosaurs."

The researchers suggest that moving from saltwater to freshwater environments may have been a late adaptation for mosasaurs during the last million years or so before the extinction event that wiped them out, alongside the dinosaurs.

The research was published in the journal BMC Zoology.